This month’s Five Books For theme is historical detectives and it has a kind of inevitability about it, given that detective fiction is my favourite genre – and there are so many wonderful books to recommend.

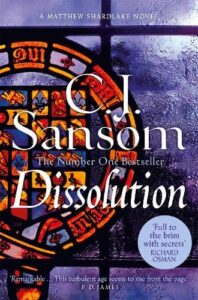

This type of detective novel sits at a delicious crossroads – part puzzle, part time machine – and few novels inhabit that space with as much authority or atmosphere as Dissolution, the first book in C.J. Sansom’s Matthew Shardlake series.

If you’ve ever wanted your murder mystery served with monastic politics, legal intrigue, muddy boots, and the slow collapse of an entire worldview, Dissolution is the book for you. It was also, surely, only a matter of time before it made its way to television.

If you’ve ever wanted your murder mystery served with monastic politics, legal intrigue, muddy boots, and the slow collapse of an entire worldview, Dissolution is the book for you. It was also, surely, only a matter of time before it made its way to television.

The adaptation, titled Shardlake after the main character, and starring Arthur Hughes as Matthew Shardlake alongside Sean Bean as Thomas Cromwell, was long anticipated, and with good reason. This is a story built for adaptation – but not without challenges.

So how does it fare, and why does Dissolution endure?

The book

At heart, Dissolution is a detective story: a lawyer is sent to investigate a murder. But almost immediately, Sansom complicates that simplicity. His detective, Matthew Shardlake, is no swaggering sleuth or heroic outsider; instead, he is cautious, physically disabled, morally conflicted, and deeply aware of his own vulnerability.

He feels real.

Shardlake’s investigation takes place during the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII – a moment of political upheaval where religion, power, and personal survival were tightly knotted together. Sansom doesn’t treat this as backdrop. The historical context isn’t wallpaper: it actively shapes the mystery.

Every motive, every silence, every lie is inseparable from the fear and uncertainty of the time.

What Sansom does particularly well is to resist nostalgia. Tudor England here is not a costume drama dreamscape. It is filthy, dangerous, bureaucratic, and tense. People are watching their words because the wrong sentence can destroy them. Allegiances shift. Old certainties dissolve (the clue being in the title).

The mystery is gripping not just because someone has been murdered, but because the entire moral order is up for negotiation.

Sansom was trained as a lawyer, and it shows. The procedural elements of the novel – interrogations, legal manoeuvring, questions of evidence – have weight and texture. This is thinking-person’s crime fiction, patient and methodical. The pleasure comes not from sudden twists, but from accumulation: details piling up until the truth can no longer be avoided.

And then there’s Shardlake himself. His disability is not a gimmick or a symbol; it shapes how he moves through the world, how others perceive him, and how he perceives himself. He is observant because he has learned to be, careful because he must be; his empathy is hard-won, not sentimental. Over the course of the series, this makes him one of the most quietly compelling protagonists in modern historical fiction.

Shardlake

Adapting Dissolution was a bold choice. It’s dense, slow-burning, and rooted in interior conflict, rather than cinematic action, twists and turns. The series wisely leans into atmosphere rather than pace, from dim lighting to bleak landscapes. The muddy courtyards, candlelit interiors, and claustrophobic monastic spaces all echo the novel’s sense of constriction – a world closing in on itself.

Casting Sean Bean as Thomas Cromwell is inspired. Bean brings gravity without melodrama, and his Cromwell is neither villain nor hero. Instead, he is pragmatic, dangerous, and unsettlingly human. This aligns closely with Sansom’s portrayal: Cromwell as a man navigating power with sharp intelligence and very little sentimentality. Arthur Hughes, who takes on the role of Matthew Shardlake, brings a thoughtful, grounded presence that anchors the series. A disabled actor with radial club hand, Hughes’s casting was rightly welcomed for its authenticity, but it’s his performance that lingers – restrained, intelligent, and quietly humane, capturing Shardlake’s moral seriousness without ever tipping into solemnity.

The adaptation also deserves credit for restraint. It trusts the material. There’s no unnecessary modernisation of dialogue, no attempt to make Tudor politics “relatable” through anachronism.

Viewers are expected to pay attention. That’s increasingly rare, and refreshing.

Shardlake himself is portrayed with sensitivity, avoiding the trap of turning his physical difference into spectacle. The camera often mirrors his perspective – lingering, observant, slightly removed – which subtly reinforces his role as witness as much as investigator.

Inevitably, some of the novel’s richness is lost. Sansom’s internal monologues and legal reasoning don’t always translate cleanly to screen. A few secondary characters are simplified, and the mystery feels slightly more linear than on the page.

But these are sensible compromises, not betrayals. The adaptation understands what kind of story it is telling, and tells it with confidence.

Book or series?

Dissolution is ideal for readers who like their crime fiction to be thoughtful rather than flashy. If you enjoy mysteries where the solution matters less than the process, this will be your thing. If you loved Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone or The Secret History by Donna Tartt, you’ll find similar pleasures here, and of course, fans of Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose, Ellis Peters’ Brother Cadfael series, or even Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall will find plenty to enjoy here too.

The adaptation will appeal to viewers who appreciate slow television – the kind that trusts silence, atmosphere, and moral ambiguity. If you’re tired of historical dramas that feel like present-day stories in fancy dress, Shardlake is a welcome corrective. Think of the way The Americans brought a specific era to life while balancing procedural tension with existential stakes, or The Night Manager, which rewards viewers who notice what isn’t said.

If that’s the kind of storytelling you enjoy, this could be your next watch.

Both the book and the series make an excellent entry point for readers who think they don’t like historical fiction. Sansom uses the detective framework as a guide rope, pulling you through unfamiliar territory without condescension. He spent years researching the period, and famously visited many of the locations he wrote about. There’s a real sense of the physical discomfort of the time – the cold, the dirt, the lack of privacy – woven throughout the books. That same attention to sensory detail is a major reason that the series feels so immersive.

The best adaptations don’t just retell a story; they reveal something new about it. Dissolution works in both forms because its core strengths – moral complexity, historical intelligence, and a deeply human detective – are robust enough to survive translation.