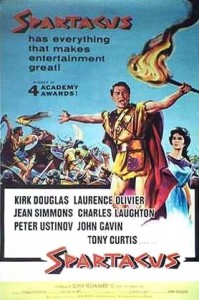

Betrayed by pirates and trapped between three Roman armies Spartacus has little choice but to march on Rome itself. At 31, Stanley Kubrick was in a similarly tricky position. Hired to replace director Anthony Mann on “Spartacus,” he found himself cornered by a script he didn’t like, a jealous Kirk Douglas and a power struggle between Laurence Olivier and Charles Laughton. After conquering all three, he would abandon the eternal city of Hollywood forever and make films on his own terms.

Kirk Douglas used Spartacus as the ultimate vanity project. Seething at missing out on the part of Ben-Hur to Charlton Heston a couple of years before, Douglas wanted his sword and sandal saga to eclipse the success of William Wyler’s movie. “Spartacus” appealed to the rebel in Douglas who had broken his studio contract to gain control over his projects early in his career to form Bryna Productions, though casting off the comfortable shackles of Hollywood tyranny could hardly be comparable to the hardships faced by Roman slaves.

Adapted from Howard Fast’s novel by the blacklisted Dalton Trumbo, “Spartacus” is an uneven mixture of Roman epic and contemporary politics. Trumbo’s thinly veiled attacks on Joseph McCarthy and the House of Un-American Activities Committee add allegorical bite. When Batiatus (Peter Ustinov) ask Gracchus (Charles Laughton) “ See to it I don’t misuse the money, ” the latter replies sardonically – “Don’t be ridiculous. I’m a Senator.”

Kubrick had directed Douglas in “Paths of Glory” and it was rumoured that the actor/producer had wanted Kubrick to direct the film from the start but the studio was worried that a relative newcomer like Kubrick couldn’t handle a project of the scale of “Spartacus.” Douglas may then have engineered a feud with Mann so that he could finally get his first choice. However, the young Kubrick quickly alienated Douglas by offering to rewrite the script, one he had inherited and deeply disliked.

Douglas backed Trumbo’s script but soon realised that he was very far from having the malleable protégé he thought he was going to get. The relationship between Kubrick and Douglas was tempestuous to say the least. As a consequence, “Spartacus” is the one film we never truly associate with Kubrick, who famously wanted to erase it from his cannon of films. “I don’t know what to say to people who tell me ‘Boy, I really loved Spartacus.’

The audience are permitted a few glimpses into Kubrick’s true style. The long take of the infamous ‘Snails and Oysters’ scene between Olivier and Curtis as Crassus tries to seduce Antoninus would later be played out to comic effect in “A Clockwork Orange” between Mr. Deltoid and Alex. The symmetrical formation of Crassus’ army observed from the slave army’s perspective has the same air of perfection as the parade of Captain Quin’s unit in “Barry Lyndon.”

Just like Alex in “A Clockwork Orange,” Kubrick seems happier when his camera is with the Romans and the British actors playing them. He extracts faultless performances from Olivier and Laughton who replay their antipathy towards each other in real life up on the screen as warring Senators. The spectacular Roman sets, circular and ordered, reflect where Kubrick’s interests really lay: with the power games of the ruling class just as in “Paths of Glory” and later still in “Barry Lyndon.”

By contrast, Kubrick never seems comfortable with the chaotic slave camp presided over by Douglas’ Spartacus. The bonding, poetry and love scenes seem false and forced. Kubrick doesn’t seem to have anything to get his teeth into and, like him, we wish to be back amongst the glorious scenery chewing of Olivier, Laughton, and Peter Ustinov’s Oscar-winning turn as Batiatus.

The real problem with “Spartacus” is the glaring lack of action that drags down the film once the gladiator school is destroyed. We wait for battles that never come. When they do they happen, they are off screen, like a 1970s BBC play. Most frustrating is the confrontation between Glabrus and Spartacus. Instead of a grand spectacle with thousands of extras we are left with a few riders burning the Roman camp at the tail end of what we presume was a battle. All tension is completely lost from this point onwards.

“Spartacus” is no different from many other Hollywood epics, the memory of them is often better than the reality. We remember our favourite scenes and block out the more tedious ones. This is the sort of genre one ought to dip into sporadically over Easter or Christmas, if only to remind oneself of the best parts.

“Spartacus” confirmed Kubrick’s suspicions of Hollywood. Rather than embrace its riches like a conquering Crassus he embarked for England where he would have complete artistic control over the rest of his films. He had good reason. “Spartacus” comes very close to lifting the lid on Kubrick’s auteur status; if he couldn’t impose himself on that film then surely moviemaking is a collaborative process? In response, Kubrick would point to his subsequent movies as his argument to the contrary. For him, “Spartacus” is the exception that proves the auteur rule.