Schulman posits that, in part, conflations of conflict with abuse spring from “[mistaking] internal anxiety for exterior danger,” causing those embroiled in a conflict to “escalate rather than resolve.” There is hope, however—Schulman theorizes that only through “conscious awareness” of our own perspectives and shortcomings can we move past the hurtful escalation of an us versus them mentality, and ultimately to understanding the perspectives of the “other side.”

If this sounds like a massive topic, it absolutely is; however, Schulman wisely chooses examples and case studies that are both timely and straightforward. One early chapter covers the widespread and horrifying police harassment and murder of black Americans—contrasted with the troubling nature of mainstream domestic violence prevention programs’ overreliance on carceral modes of justice, a problem that has also been well-documented by WOC activists, including Emi Koyama (link goes to .PDF document), and the INCITE! collective.

Other chapters take on the recent systemic discrimination—with the support of law enforcement, public health and medical organization, and the legal system—against HIV-positive people in Canada; the language of victimization and processes of escalation in interpersonal conflict; the nuances of the after-effects of trauma and control issues; the rise of the new pro-family model in the queer community, and how such an in/out group dynamic mirrors an “ideology of familial Supremacy” while aligning with toxic, right-wing ideals of “family values.”

The book’s final case study, which centers on a harsh 2014 military attack by Israel that targeted Gaza, is unfortunately its weakest. Though the content of this chapter fits incredibly well with Schulman’s overall argument, her focus on the experience of watching the attacks unfold via social media posts, responses, and conflict—which she calls her own “individual recognition process through the first weeks of the massacre” in order to demonstrate the distorted group thinking, shunning and dividing processes that she has examined previously—becomes muddled precisely because of the social media format.

Although the reproductions of Tweets—along with Facebook posts and comments—are helpful in providing context, these reproductions take up quite a bit of page space, and at times I felt like I was simply reading Schulman’s Twitter and Facebook feeds, to the detriment of her analysis. Substantive analysis is something at which Schulman excels; had she included more of it in the final chapter, it would have made a powerful ending case study.

Despite the final case study’s analytical shortcomings and minor flaws elsewhere in the book, Conflict is Not Abuse should prove to be essential reading for people interested in psychology, group dynamics, and social justice activism. Those who have been around the Twitter and Tumblr activist communities for some time and have come face-to-face (so to speak) with other activists who—even with the best of intentions—end up, in Schulman’s turn of phrase, “hiding behind keyboard[s]” and overstating harm done by those who are ultimately on their same side of the political spectrum will recognize the hurtful group dynamics, escalation tactics, and after-effects that Schulman carefully examines here.

Anyone who has found themselves on the “wrong” side of a Twitter pile-on for an honest mistake, who has read game developer Porpentine’s searing essay for The New Inquiry on activist intra-community dynamics and how online interactions can (unfairly) make or break someone’s status as a “good” or “bad” community member, or who has seen the online activist community repeatedly eat its own, is sure to find Schulman’s book both relatable and enlightening.

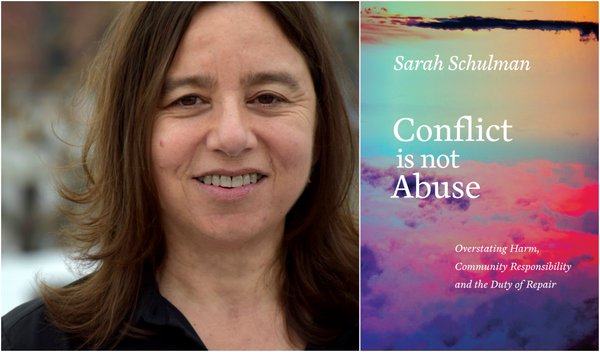

Conflict is Not Abuse (ISBN: 9781551526430) will be released in October 2016 by Arsenal Pulp Press.

Photos: Arsenal Pulp Press.