Time is strange – startlingly real to the human body, and not real at all if you’re trying to reconcile the theory of relativity with quantum mechanics. Twenty five years have passed since Mark Danielewski published his debut novel, House of Leaves, and no years have passed at all.

Whether time and space are real or not, looking back can be a good endeavor. Especially right now.

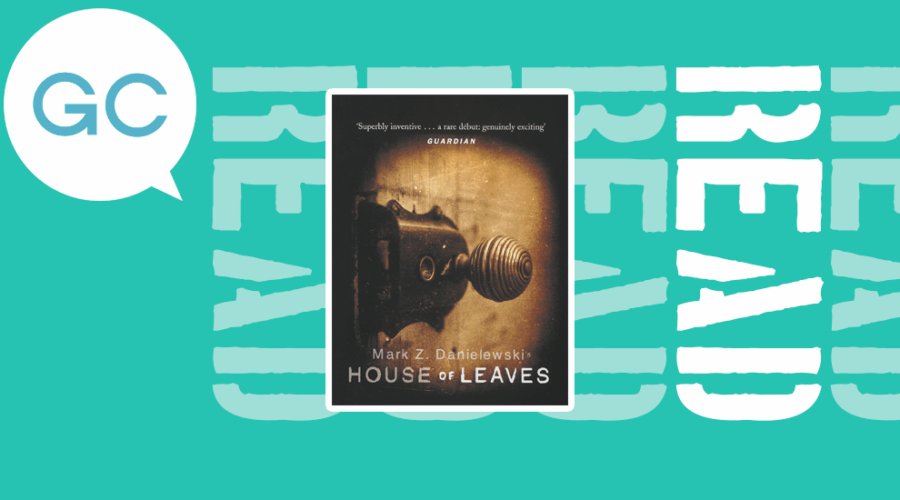

A cult horror novel and a love story all at once, House of Leaves is a rare beast – messy, ironic, terrifying, combining epistolary fiction, meta fiction, and strange magic that leaps off the page and glitters menacingly in your peripheral vision.

If you’re a fan of literary horror and/or a fan of academic satire that may not be satire after all, this book may be for you. For reasons that best remain unsaid, I’ve begun rereading it this year – without first noticing that it is a quarter of a century old now.

Confusing and often frustrating, House of Leaves is actually the perfect book to read, or reread, in the age of ubiquitous social media. It will take you out of doomscrolling, if not doom itself. It will help you rewire those neural pathways that have become too dependent on instant gratification – if you allow it to.

The premise will sound preposterous at the outset. A young guy working at a tattoo parlor finds a manuscript written by a recently deceased old guy. The manuscript focuses on a documentary that may or may not exist, a documentary about a house that is larger on the inside than it is out the outside, and the terrors that wait within.

Tattoo parlor guy goes about publishing the original manuscript while adding his own discursive footnotes throughout and slowly going insane. The entire thing is a gorgeous mess, sometimes satirically, but often genuinely scary. Mark Danielewski’s sister, the musician who goes by Poe, wrote a companion music album, Haunted, about the entire thing too – it’s chilling and ironic in its own right.

People have described the House of Leaves universe, to borrow a term from Marvel & Co., as psychedelic, and that was my initial impression too, back when I picked up the book as a high schooler.

Yet over the years, I’ve often thought about it with sentimental longing.

Coming back to this book 25 years later, I understand why. House of Leaves carefully captures the fractiousness of our reality – including that which we love most about life, which is our families, our tender moments, the endless human quest to beat back the night.

The documentary at the heart of the book is shot by a celebrated but troubled photographer who has moved his model girlfriend and their two kids into an old Virginia country home away from the static buzz of New York City. They are settling in when the home begins to grow on them – literally so. Defying the laws of physics, new rooms appear, and they are dark. There are secrets and danger within. There is trouble and obsession that this family may not survive.

Certain books are best read in autumn, and House of Leaves is one of them. When I first started reading it, I was a gangly girl, an occasional model myself, taking breaks between shifts at my uncle’s coffeeshop, listening to the wind scrape the leaves down the strip mall sidewalks.

It’s no coincidence, I think, that one of the book’s most poignant moments occurs at Halloween, the last night of October, with the year winding down and the smell of sweet rot rising from the forests and suburban groves.

Halloween is always a turning point – and it’s only silly on the surface.

All things must pass, this book says, but they will grow strange beforehand. I understood that intuitively as a kid who hung out in strip malls, and while I wasn’t cerebral enough to also understand all of Danielewski’s references at the time, the prose is so direct that it didn’t matter. Which is to say that you can safely read House of Leaves without picking up on everything at once.

Returning to House of Leaves now is like returning to an old friend, except that both of us have grown (houses change on the inside, and so do good books. We just don’t notice that at first, this knowledge tends to arrive later). The book is haunted, and so am I, and so is every reader who is adventurous or reckless enough.

As a lifelong David Lynch fan, I have always been in love with his playfulness, which often permeates even in his darker artistic moments. House of Leaves is similarly playful – in fact, if you’re discovering Lynch’s work following his death, I recommend this book especially. The weird, the uncanny, the predatory, sabertoothed side of American life is embedded within.

And there is also hope here. And love. A desperate kind of love, which may be the best kind after all. Maybe the only kind.