During its half century of Soviet and Nazi occupation, more than 47,000 Latvians (nearly three percent of the country’s population) were prosecuted and punished. Latvia doesn’t want that dark period to be forgotten or minimized. No mincing of words or events. No softening of tone in the name of European unity. Latvia and its Baltic neighbors, Estonia and Lithuania, are intent on reminding the world of those dark days of occupation, first by the by the Soviet Union in 1940-41, then Nazi Germany from 1941-44, ultimately culminating in the post WWII Soviet occupation for 46 years until independence in 1991.

The three countries intentionally refer to those decades as an “illegal annexation”, an “aggression” and an “occupation”. When they entered the European Union in 2004, they put fellow EU countries on notice that their annexation by two totalitarian regimes needed to become part of the European political agenda.

Russia denies any culpability for those dark decades. It says its occupation was legal; that it liberated Latvia from Nazi Germany and it refuses to recognize any of the Latvian narrative about what happened, claiming the country wanted to be annexed.

Back then, faced with the crushing occupation of two larger regimes, Latvia had little hope of mounting a successful armed resistance, though it was attempted by a group called the Forest Brothers. The path to freedom came from non-violent resistance, eventually formalized as the Latvian Popular Front during the final years of Soviet occupation. Together with the Estonian Popular Front known as Rahvarinne and the Lithuanian Peoples Movement called Sajudis, the resistance movements of the three contiguous Baltic countries united in a coordinated organization called the Baltic Peoples’ Movement and Assembly.

Today Latvia continues its resistance efforts by showcasing evidence in the face of Moscow’s denial of history. It has four museums in its capitol of Riga dedicated to the jarring reality of what happened behind the Soviet Iron Curtain – the National History Museum, the Occupation Museum, the KGB Building and the Popular Front Museum. Alone or combined they tell a graphic story. The chilling KGB Building is the site of some of the worst Soviet atrocities. Visitors on tour can physically experience the terrifying basement cells, dank, psychological interrogation rooms and black and white photos of Latvians taken there who never returned.

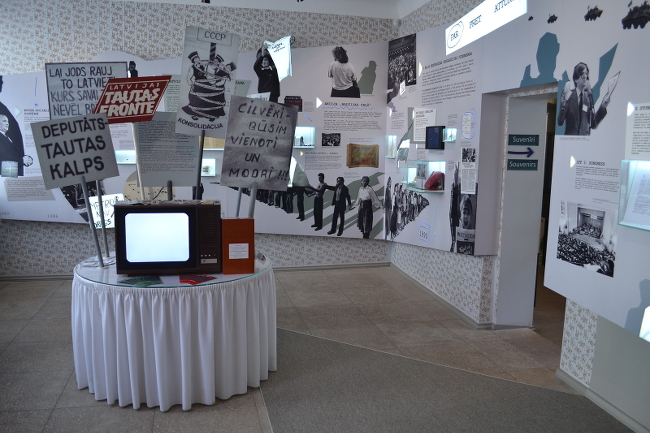

The museum dedicated to Latvia’s Popular Front is also in the same building it operated from during Soviet times. Outside it’s an unassuming multi-story structure. Inside, it’s the archive of television footage, photos, documents, interpretive plaques, interviews and exhibits telling the resistance story of Latvia and the Baltic Peoples Movement and Assembly.

Organized in October, 1988, the Latvian Popular Front became the combined force of resistance groups and individuals who had their origins in the first decade of Soviet and Nazi Germany occupations. From the 1940s through the organization of the Popular Front, it was artists, writers, poets and students who were on the dissident front lines. In the early years, they were joined by members of the Latvian military and police forces and by landowning farmers.

They published underground newspapers, distributed pamphlets, raised the banned Latvian flag and organized gatherings, grouping themselves into underground efforts – Officers Union, Guards of the Fatherland, Latvian National Legion and Young Latvians. The Soviet retaliation was swift. Many of the resisters were arrested and imprisoned or worse.

At the end of WWII in 1945, when Latvia was ceded to the Soviet Union under a secret pact signed by Stalin and Hitler, Moscow began to “Russiafy” Latvia, deporting, imprisoning or killing anyone suspected of being part the resistance and replacing them with people loyal to the Soviet cause. During the nearly five decades of occupation, over 800,000 foreigners from other Soviet republics entered the country and were given jobs and homes of deported ethnic Latvians.

In March 1949, Moscow again cracked down. This time their target was Latvian farmers who had opposed Soviet efforts to collectivize agricultural land. 42,000 Latvians were deported to Siberia over a two day period that month.

Latvian underground resistance continued. Dissidents read forbidden western literature, listened to western shortwave radio broadcasts and wrote and distributed articles. Through nearly four more decades of Soviet repression when movements faltered because their leadership and members were imprisoned, new leaders and new groups emerged.

By 1985 when Mikail Gorbachev declared “glastnost”, loosening restrictions on some of the social and political policies in the annexed Soviet Republics, Latvia’s resistance movements were ready. In 1986 they formed “Helsinki 86”, a visible anti-Soviet political organization. In 1987, two demonstrations were organized, one to commemorate the 1941 mass deportation and another to protest the Stalin/Hitler pact ceding the Baltic countries to Moscow.

A year later, the first meeting of the Popular Front occurred bringing together resistance groups and founders of “Helsinki 86” into one movement. 100,000 Latvians joined immediately with the organization quickly growing to 250,000 members – twelve percent of the country’s population. In the beginning it had a moderate goal – autonomy for Latvia within the Soviet structure. Under membership pressure it developed a more radical mission – full independence from the Soviet Union using non- violent resistance so Moscow couldn’t use their efforts as an excuse to invade with military force.

Within months, the new organization met with the emerging national resistance movements in Estonia and Lithuania forming the Baltic Peoples Movement and Assembly. The combined group planned an August protest event so dramatic it could not help but get the attention of Western journalists – The Baltic Way – bringing together over two million Latvians, Estonians and Lithuanians to form an unbroken 600 kilometer human chain from the capitol of Estonia south through the capitols of Latvia and Lithuania.

Next, the Latvian resistance movement took on Soviet environmental degradation halting plans for a Riga metro. A demonstration opposing the construction of a hydroelectric dam on the Daugua River drew 500,000 protesters – a quarter of Latvia’s population.

In May, 1990, Latvia held its first post “glastnost” elections. The Latvian Popular Front ran candidates winning a majority in the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic Council and capturing the seats of Prime Minister and Deputy Speaker. The newly elected majority passed a resolution calling for independence. Concurrently, similar political organizing was happening in neighboring Estonia and Lithuania. The Soviet crackdown was immediate with Lithuania, taking the initial brunt of it. On January 13, 1991, Soviet forces attacked government buildings and TV towers in the Lithuanian capitol, killing 14 people.

Latvia’s Popular Front immediately organized, urging citizens to build barriers in front of the capitol’s government buildings. A week after attacking Lithuania, Soviet forces entered Riga taking over two government buildings and radio and television stations. Seven people were killed.

As the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the Popular Front majority of the Latvian USSR Council moved quickly, declaring independence and urging the United Nations to recognize the country.

Today Latvia continues to institutionalize its history by telling its story. As a country bordering Russia, that’s critical. But in these dark political times, with invasions that can take forms other than a physical incursion, we all need to learn the truth telling history from Latvia and the other occupied countries who lived behind the Soviet Iron Curtain.

Photo: Ann Randall