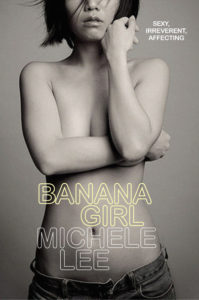

“Writers should be bold,” says novelist and playwright Michele Lee from Australia. “They shouldn’t be sociopaths but they should be bold.” In her memoir “Banana Girl”, Michele narrates her lifestyle as a young Melbournian.

The novel details her turbulent relationships with lovers, friends and family members. We know that these have always been a favourite source of inspiration for artists. We cherish artists who share the good, the bad and the ugly of their lives. Their need to elaborate on their surroundings and what happens to them is not just a egotistic drive. Their own experience is a mirror for the audience or the reader.

But of course, there are always two – or multiple – sides to every story. Involuntary muses are not always happy to be turned into characters of a novel or have their portrait hanged on a gallery wall. This especially true if the art deals with intimate, personal and potentially embarrassing themes.

Back in the day, artists could hope their subject matter was unaware of their inclusion in the work. Today, though, that’s virtually impossible. An image or a book review can be infinitely shared on social media. At the same time, art exhibitions are not just for the elites anymore.

“If your main objective in writing about your life is to defer to the imagined feelings of others, then you’re probably going to end up in a constrained mindset, and hit a lot of walls in writing.”

Michele is well-aware that, when people around you become the inspiration for characters, you run the risk of accidentally hurting someone’s feelings. But within reasonable limits, she prefers begging for forgiveness later rather than seeking permission. “If your main objective in writing about your life is to defer to the imagined feelings of others, then you’re probably going to end up in a constrained mindset, and hit a lot of walls in writing.”

Only when a first draft is laid out does Michele make decisions about what to keep in and how to reconstruct moments. In this phase she asked some of the major people chronicled to read their ‘bit’. “One of the currencies you’re working with in memoir is real people. So of course at times they’re all you can think about when you’re re-writing and editing.”

An early reader of Banana Girl, Mary, Michele’s sister, was shocked reading about her character: “My sister had pretty much summed up who I was as a person at the time that the book was written. After I got over the shock, I was fine with it.

“I did not feel the need to ask for control over the way Michele was writing me. Reading Banana Girl didn’t affect my relationship with my sister at all.”

Michele’s attitude was different when writing about the people she had less of a relationship with.

“In that case I didn’t spend as much time thinking ‘What will they think if they read this?’ because I suspected they wouldn’t hear about it or be going out and buying it.”

She also points out that a memoir is not about factual truth but more about memory, perception and sense.

“It’s my version of the truth,” explains Michelle. “And of course the dialogue is not verbatim. And maybe a dress was cobalt blue not emerald green.”

Singaporean artist Geraldine Kang knows how deceptive this idea of art conveying the truth is: “A photographic portrait is always an exchange between two identities and usually it is more about the photographer than the person being photographed. You are the one controlling the lens, you are the one telling them how to pose, you are the one trying to elicit reactions or expressions.”

Geraldine has realized many photographic series starring friends and family. For her, art is a way to process her thoughts and feelings and to get herself out of her head. In the award-winning series In the Raw, she depicted her family members in surreal situations dealing with nudity, aging and death. The artist defines In the Raw as a “shock treatment” to introduce her parents to her art practice, which in the beginning they didn’t understand.

When approaching sensitive themes, it is always good to look for models in other artists who have tackled similar challenges. For In The Raw, Geraldine was inspired by photographers Tierney Gearon and Sally Mann.

“They use the naked body in a way that is quite natural. It’s not normal for people to bare their bodies in public, and nudity in proximity of the family is particularly uncomfortable. There are so many layers of meaning put upon the naked body. I was really fascinated by that and with In The Raw I transplanted this idea into my own family.”

“A lot of people ask me how I got my family to take off their clothes. And they are surprised when I told them it didn’t take that much.”

Nudity is a taboo both in Singapore and in Geraldine’s family, but that didn’t discourage the artist.

“A lot of people ask me how I got my family to take off their clothes. And they are surprised when I told them it didn’t take that much. I just told them: can you do this? They would be a bit uncomfortable but they would do it anyway.”

The artist now looks at In the Raw as an exercise of acceptance on both sides: “I see the work as a sort of compromise between me and my family. I show them what I am dealing with as an artist and see how far are they were willing to go with me.”

Mr. Kang, Geraldine’s father, said that when his daughter asked the family to take part in the series, he had no idea what she was doing. He only knew it was her school project.

“I didn’t probe further as we did not want to add more stress to an already stressful situation. As parents, we try our best to help her in whatever way we can.”

Mr Kang explains that, being brought up in a conservative family, at first he was taken aback hearing about Geraldine’s project.

“Took awhile to convince myself and my wife it’s all about art and to just place our trust in her.”

At the same time, they didn’t set any boundaries at all on Geraldine’s creative process.

“I was fine as long as she didn’t make us a laughing stock through her pictures.”

In The Raw gained great success and was repeatedly exhibited in art galleries. This accomplishment, together with Geraldine’s stubborn commitment to her craft, helped her parents understand her seriousness about art.

“Support really did change. They still don’t know what I’m doing, but they come to my shows. Sometimes they bring people to the exhibitions and they even help me with my work, my dad especially.”

When thinking about In the Raw, Mr. Kang notes that, for him, the series “is her way of bringing a message across through pictures. I kept telling myself this is art.”

In terms of advice for writers and artists who are pondering what to share of the life of those around them Michelle Lee has a few tips: “Read the work of others, hear memoirists speak about their work, find mentors, find trusted people to give feedback on your work. Sometimes before I sit down to write a play I write a concept document or a slightly longer manifesto.”

This might be a useful exercise before plunging into the creative side of things.

“You can return to it throughout your journey. It’s always really rejuvenating to go back to what you originally said your intentions for writing a particular piece was.”

In the delicate balance between creative freedom and respect for others, both Michele and Geraldine let empathy be their guide.

“It’s about coming in and out of empathy pitstops. It can’t always be in the foreground, but it should be a place you stop in at.”

Image credit: Jannis Edelmann