Why was it okay for Christiania residents to live illegally for over 40 years? What type of precedent does that set to the rest of Denmark, as in, what if everyone else did the same thing?

Although open to the general public, borders are strictly and vehemently controlled when it comes to new residents. Selection is carefully made as all decisions in the commune are; a community vote, which only occurs when an opening is made available. Although strict, that may be the reason why Christiania still exists today, as it has been able to keep the vibrancy of youthful socialism with the constant temptation of the market economy waiting to capitalise on the authenticity of the experience, a fate that a countless number of once thriving ‘hippy’ communes have succumbed to.

For example, Bisbee, Arizona, a once thriving mining town turned hippy commune after the closure of the mine left abandoned buildings ripe for squatting. Bisbee has since become Estately.com “10th best place for hippies” in America. 20 years after its 1960 inception, Bisbee was overrun by a wave of yuppies migrating from nearby Tucson in search of affordable rent and an edgy, alternative living experience that Bisbee was actively advertising. In 2016, decades after any sign of authentic hippy commune was overrun by developer-instigated urban reform, the official tourism website advertises a utopian community where you can ‘Be refreshed. Be inspired. Be yourself.’ Contrasted with the VisitCopenhagen website’s notice on Christiania, it is evident why the authenticity of the commune has sustained. The website states:

For your own safety, visitors are advised not to film nor photograph in Christiania, especially not in the area in and around Pusher Street, mainly due to the hash dealing, which is illegal in Denmark. At the entrance you will find signs indicating ‘do’s and don’ts’ in the area. We advice you to take them seriously and follow them for your own safety.

How does a town with the name ‘Freetown’ have a zero tolerance immigration policy? Is a less than free movement of people into the settlement necessary to monitor its residents and ensure its livelihood? Or is it a symbol of the over-controlled bureaucracy that its founding members sought to revolt against?

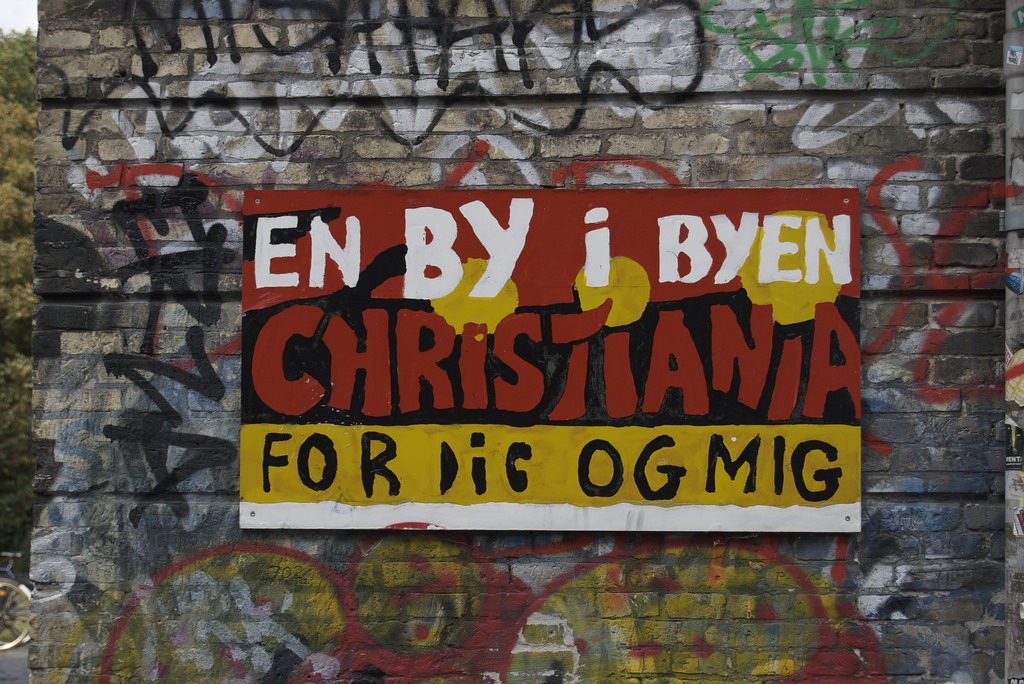

I was fortunate enough to personally walk through Christiania on a free, guided tour given by a long-standing resident and local expert. The sites, sounds, and even smells were unlike anything I had experienced in the surrounding city, and the sensation of entering a new place was immediately felt. I was one of 1 million tourists that entered Christiania last year, a statistic that is astonishing based on the fact that there is no infrastructure to accommodate or encourage outsider engagement. There is no hotel, no Starbucks, no visitors centre, etc. There is simply people living their lives in a way which questions traditions and norms that have been instilled in us from birth. Whether it’s the intrigue of differentiation, or simply a facilitator of self-critique on our overly privatized lives, visitors flock to Christiania without residents asking them to.

Christiania reminds me a lot of the bar that doesn’t advertise, doesn’t have a sign on the door, but has a lineup 4 nights of the week of people hoping to have the opportunity to post an Instagram picture of themselves inside. The only difference between Christiania and that bar is authenticity and longevity. The bar owners set out to create an experience of being ‘cool’ or alternative which is why they allow graffiti tags on the washroom mirror, or cover the walls with posters of classic rock bands its patrons have never heard of. The issue with creating authenticity is that it will always result in being contrived and shallow. This is why that bar will close down after six months and a new place selling the same identity opens up down the street, while Christiania remains thriving 42 years after its inception.

Why do you think as a society, we are often obsessed with people who are radically different from ourselves? I believe that we often feel stuck in a routine of day-to-day life and fetishize a means to break that monotony. Christiania offers that kind of shock to our perceptions of normalcy that we both consciously and subconsciously desire.

The concept of fostering an ‘authentic,’ vibrant, and creative atmosphere extends beyond the world of bars/restaurants and has been discussed by prominent urban theorists that focus on place making and the illusive creative economy. Christiania has harboured the idea of establishing a creative economy decades before Richard Florida coined the term, and continues to be a hotbed for knowledge-based commercial activity as well as unparalleled cultural richness. Architectural expression is encouraged, public space is intertwined with private dwellings, possessions are shared, tolerance is so high it is insulting to even use the word to describe resident’s values, murals are the dominant façade treatment, and the list goes on.

The most interesting aspect uncovered in the research is the fact that communal living is often referred to as an ‘experiment,’ and I agree that it is. It’s a social experiment to see how individuals are able to navigate through self-governing and creating a new political paradigm, it’s an architectural experiment of utopia as it uses built form to organise people in a way that encourages the decay of private life, it’s an economic experiment which looks at a new configuration of the market economy that isn’t purely profit driven but rather focused on sustenance.

The only issue with calling Christiania an experiment is that there are no scientists involved, no subjects, no controls, no hypothesis. it is simply a product of radical thinkers that were able to band together in the face of adversity. I believe that the fact we have labelled it an ‘experiment’ is to feel more comfortable with the idea of it being a threat to the lifestyle that has consumed the planet. Labelling it an experiment gives it an air of danger, of clinical absurdity, of differentiation from the norm so severe that its residents are equated to rats in a maze being observed by intellectuals.

I will conclude this post with some more questions: the energy around the critique of the nuclear family reached its height in the 1970s and coincided with the communal living ‘experiment,’ but what happened since then? Why did the movement seemingly die? Also, are we currently entering a new paradigm shift related to the relationship of private-public life with the growing popularity of the shared economy? Can we consider apps that facilitate sharing of our homes, cars, tools, clothing, etc. a new virtual commune that doesn’t require physical space to thrive?

Photo credit: claire rowland/Creative Commons