As a Chinese kid growing up in America, Chinese New Year meant three things: lots of dining with family members whose names I couldn’t remember, “Kung hei fat choi!” proclaimed at every turn, and lai see or red packets. (Hongbao in Mandarin.)

Leading up to Chinese New Year, or the new year in the lunar calendar, my mom would click her tongue and grumble to my dad at night that, “Ai yah, I forgot to go to Chinatown to get lai see. When are we seeing Auntie Eleanor?”

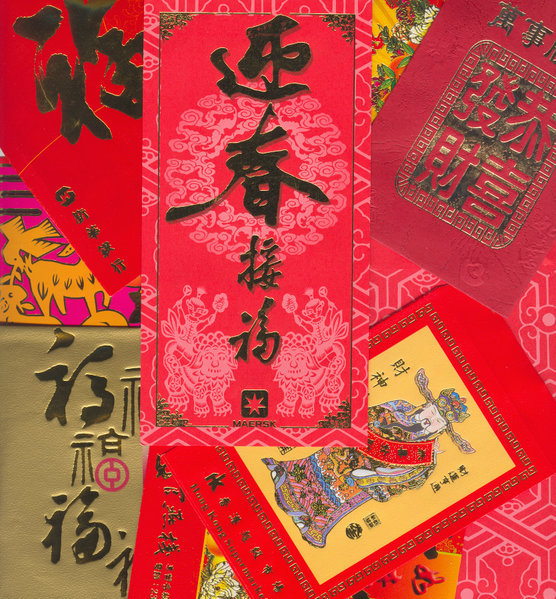

Sometimes I’d go with her to one of the shops in Chinatown that would be decked out in red and gold (auspicious colors) for the New Year. I don’t know how she chose which shop to go to, so many stands and shops in Seattle’s Chinatown seemed to burst forth with red packets and Chinese New Year decor, but she had the one she liked because maybe the owner was “older and honest” or “lived in Wan Chai like I did in Hong Kong.”

Mom would count under her breath in Cantonese how many people she needed to give lai see to, then purchase a bundle of them. A teller at a bank, she’d been slowly trading in her old bills for crisp new ones to put inside lai see, as was the tradition. Whenever she came across a rare two-dollar bill, she’d trade in her money for that too. I got so many two-dollar bills as a child.

On the first day of Chinese New Year, it was like waking up to a “Chinese Christmas” in my Americanized mind.

My mom and dad would hug each other and say, “Kung hei fat choi!” then turn to me and do the same. If I didn’t respond in kind, my mom or dad would pause expectantly and ask, “What do you say?” And I’d respond with a shy “Kung hei fat choi,” or “Congratulations and be prosperous” in Cantonese. Even then, I knew my Cantonese was fading and my accent was bad.

Then I would receive the coveted red packet, the first of the day. Printed with gold Chinese words on them, sometimes a gold sketch of whichever animal’s year it was on the Chinese zodiac, I’d covertly squeeze the packet searching for the thickness of multiple bills. Traditionally in Hong Kong you’re not supposed to put more than one new bill (never coins) into the lai see, but after living in America for a while, we did away with that tradition.

If you forgot that Uncle Steven had three kids not two, it was easier to just jam a few singles into a lai see rather than redo all of his ungrateful kids’ packets with equal amounts. You always give all the kids the same amount, and you should always give the same amount to others as you gave to your own kids – though I know I didn’t get the 20-dollar lai see some of my rich Canadian cousins got.

Growing up, we always knew when an uncle or auntie had forgotten one of us existed, as you’d get the lai see with a couple weathered bills folded into it. But we didn’t care – free money!

When given my lai see from my parents, if I casually took the packet with one hand I would be scolded.

“Take it with two hands and say doh je,” Mom would correct. Doh je is the specific thank you for gifts, in Cantonese. Doh je saai if you want to lay it on thick with your aunties.

When I would start to tear into the packet Mom would bark, “Ai yah! Don’t open it in front of me! You never open your lai see in front of the person who gave it to you. Open it in private!” So I’d put it in my pocket. It was more fun to compare hauls with my cousins later anyway.

But unlike Christmas, I didn’t give my parents or auntie or uncles lai see in return. Being younger than them (and unmarried), it was their duty to give me lai see. Even now that I’m married and an adult, I don’t give my parents or older relatives lai see, that would be weird and potentially disrespectful. As the second to youngest in my family, my responsibilities to bestow lai see are rather minimal.

If I were to be in the same place as my nieces, nephews, or younger second cousins then yes, lai see would be in order – because of the whole “old and married” thing. I should also give lai see to the children of my close friends. You wouldn’t give lai see to married peers, but giving lai see to their children is a way to show them respect. No children, no lai see. Oranges for everyone!

Oh, and married people are also supposed to give lai see to single people during Chinese New Year. I don’t think I’ve ever done this in the US or Hong Kong, but my parents’ generation still does? Sorry single friends, I’m slacking.

Basically if you’re older than someone, you’re married, and you’re related to or you are close-like-family with someone, you are the lai see giver. This also goes for the work place – if you’re more senior, you should have those red packets at the ready for your juniors. The amounts of money can vary depending on your relationship. A junior coworker might get a relatively small token of your appreciation, whereas your nanny, housekeeper, or doorman might get much more.

Kids more often than not get even denominations in the 10 dollars and under range – just never four dollars, or for that matter 14 dollars or 40 dollars or 444 dollars. While lai see should be given in even numbered amounts, nobody should give a lai see amount with a four in it. The words for “four” and “death” are very close in Cantonese. “Four” numbers are considered unlucky. Even now, many buildings in Hong Kong don’t have a fourth or 14th floor listed (like the western 13th floor).

Very generally speaking, the average Chinese New Year lai see amounts in the US range from two to 20 dollars. Though I did get a 100 dollar lai see from my auntie when I graduated with my masters degree. I kind of wanted to frame it (I didn’t – free money!).

Despite this seeming obsession with money, Chinese New Year is a time of renewal and good will. The spirit of Chinese New Year lai see giving is to wish someone a prosperous new year, show appreciation, show care. Ideally it shouldn’t be all about making bank, but rather as a way to start the New Year right.

Historically, lai see likely originated in China during the Sung Dynasty when “the currency changed from goods to money.” Right before the New Year was seen as a time to settle debts. So to begin the New Year in prosperity, lai see were a way to replenish money lost to debt collectors.

Additionally, lai see are seen as a way to ward off the evil Chinese spirit Sui. Centuries ago in China, it was believed that Sui would go after sleeping children on New Year’s Eve. As the story goes, one year a child’s parents gave them eight coins to keep them awake and safe from Sui. The child fell asleep, but when Sui came to attack, the Eight Immortals (disguised as the coins) chased Sui off. Over time, New Year’s money evolved from coins strung on red thread to the red packets used now. In China, the red packets are also called yasui qian or “suppressing Sui money”.

Aside from suppressing evil spirits, lai see have a more practical application.

When I lived in Hong Kong, where Chinese New Year is the holiday – schools and businesses shut down for days, parades and celebrations dot the city, everything is decked out in red and gold – giving lai see to the people who make your life better is a must. If you don’t it’s rather rude. As a place where “luxury” services are more common than in the US, giving generous amounts to your building’s security workers, doorman, your regular laundry person, your domestic helper (housekeeper), janitorial staff, and other such jobs is important, classy, and expected.

There has been some backlash with people complaining that doormen, for example, turn up their nose at less than the amount they feel “owed”, but nonetheless the giving of lai see continues among most Hong Kong Chinese locals. Many people see lai see as a “bonus” for a job well done during the year.

But as children, we saw lai see as a merely a bonus for existing.

After my immediate family’s lai see and “Kung hei fat choi” exchange, we’d all load up into the Suburban and eat lunch in Chinatown with extended family. More lai see and “Kung hei fat choi” would be exchanged, aunties would fight over the bill, and the kids would steal away to compare cash takeaways. (We also thought it was hilarious that if you mispronounced “lai see” with the wrong tone, the meaning changed to “to poop your pants”.)

At night we’d end up back at my uncle’s house eating more food and talking story late into the night. I didn’t really understand Chinese New Year, and I didn’t really understand lai see, I just knew that this was the time of year when my parents took prosperity and good energy very seriously.

So whether you’re getting ready to hand out stacks of red packets or you’re planning on being a tad more conservative with your offerings (like me), do think of lai see as a way of distributing good energy for the New Year. Good energy that goes around, comes around, so who knows? If you follow proper lai see giving etiquette, you may find yourself looking at a very happy new year.

Kung hei fat choi!

Featured Image via Creative Commons