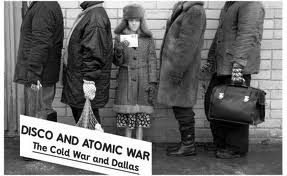

In “Disco and Atomic War” Estonian filmmaker Jaak Kilmi approaches what is a pretty dry, well-tread political topic – the power of media to not only prop up totalitarian regimes but to take them down – with lighthearted whimsy. Through the use of archival footage, talking head interviews, staged reenactments – and most importantly, cheesy clips from “Dallas” and “Knight Rider” – Kilmi takes us on an offbeat historical and personal journey, back in time to 80s Tallinn. It was an era when, using makeshift antennas to hijack broadcasts from Finnish TV, intrepid Soviet citizens came under western influence, and began to unite to fight for more individual freedoms. (And for the right to do the hustle and find out who shot J.R.)

Global Comment spoke with the doc’s director prior to the film’s DVD and VOD release on February 25th.

Lauren Wissot: I’m not too familiar with the Estonian film scene, though your doc possesses the same sort of oddball charm I associate more with Scandinavian filmmakers than with those from the former Soviet Union (and certainly not with American directors). Did Finnish sensibility itself get broadcast into Tallinn’s culture as well?

Jaak Kilmi: Actually, Estonians have no common mentality or humor with Russians or Ukrainians or Kazakhs. Yes, Estonian temper – and the language – is quite close to the Finnish one. And also the humor I think. It’s really more in the genes than from the Finnish TV broadcasts. (laughs)

LW: You won the Best Documentary award at the Warsaw Int’l Film Festival awhile back, and I assume you’ve screened all over Europe in addition to the theatrical release in the U.S. So how varied have the responses been? Do certain countries connect with different aspects of the film?

JK: The warmest response I got was in Eastern Europe – and Finland. The common past was the reason, I guess – the western pop culture as it was seen and consumed by children in those days.

LW: You employ an immense trove of archival footage (and music) in addition to clips from “Dallas” and “Knight Rider,” which renders the doc a nonfiction period piece of sorts. Even the reenactments, and the more recent interviews with the talking heads, could have been shot in the 80s. Why take this stylistic approach?

JK: In a way it’s a nostalgia film for those who value their absurd childhood memories – like I do. We chose all the locations, props, costumes and visual style (the colors, the interview style, etc.) from the 80’s. I think this approach works pretty well in the film.

LW: Is this idea of “soft” power by western forces contributing to the collapse of the Soviet Union contested, or still a sore spot, in Estonia (and elsewhere)? Were there folks who refused to be interviewed on camera? (Conversely, did you attempt to interview any cast members – say, David Hasselhoff – from those influential 80s shows?)

JK: Yes, there was one guy who refused to give us an interview because he thought that our approach was too speculative. In a way he was right. Our film was based on childhood memories, rumors and conspiracy theories. True historians can question everything that we say in this film. (laughs)

But that doesn’t bother me. It’s the story of my childhood, where the fiction played a more important role than the gray reality. No, we never tried to contact the cast members like David Hasselhoff. All the talking heads in our film are more or less the specialists who could explain things in a broader political/economic/historical context.

LW: Could you talk a bit about your own personal influences? Interestingly, I see mostly fiction filmmakers – as the doc has a sort of Wes Anderson visual quality, that innocent child’s POV, mixed in with an older, ironic tone reminiscent of Aki Kaurismäki’s work.

JK: Actually, I was looking for the right approach and visual style for my film for a pretty long time. Roy Andersson’s style inspired me a lot. But the old black and white photos that my father took of our family in the 1980’s inspired me even more. People were staring into the camera with serious faces in these photos. I looked to these photos and tried to learn from the style, composition and facial expressions I saw there.

Reenactments are tricky things – usually I don’t like them in documentaries. It’s so fake. I never buy it. I thought that if I show a collection of stylized clumsy portraits I’m not cheating anybody at least. And the god of documentaries can forgive me. (laughs)