“I’m sorry, but I don’t think there’s a place in this company for you.”

Jake Gallo heard this on his interview and he was so insulted, he flew into a rage that he had to be dragged out the office and beaten. He was furious and offended. It was blatant discrimination, Jake knew. Other candidates were interviewed and accepted while he was rejected. He had the skills. He had the intellect. He even had the right attitude. It wasn’t that Jake was black, a woman, or Asian.

It was because Jake Gallo was a chicken.

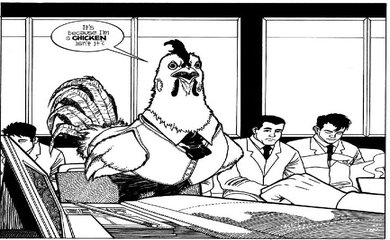

This is how the graphic novel Elmer by Gerry Alanguilan begins. It is a literary artwork in black and white that is as clear as its depiction of violence and racism in an unfair world. In this universe, chickens are as sentient and intellectual as humans. They talk and have intelligent conversations. They drink coffee out of cups and eat cooked food. Of course, they are not cannibals. Instead, they eat roast duck. They wear clothes and go to movies or work as nurses or actors. They are, in essence, part of the human race.

Reading this novel, Alanguilan can’t be described exclusively as an artist or a writer. Inspired by the chickens that roam freely in his hometown, he wrote snippets on chicken behavior in Stupid Chicken Stories and a supposed sequel, Ultimate Chicken Story, but it evolved into Elmer. Gerry Alanguilan is, first and foremost, a storyteller, and the story he weaves in Elmer is both tragic and sublime. Jake Gallo, premier writer and son of Elmer, who was among those Gallus gallus species who gained a human consciousness in the middle of being butchered in a poultry farm, is an indignant and angry chicken, uh, human. He believes that the world still sees his kind as nothing but “little animals they used to eat”. He even throws a tantrum when he hears that his sister, May, is getting engaged to a human.

Jake lives in his own angry world where he fights for equality but never truly believes in a day where he can be treated like any other human being. With the news that his father is suffering from a stroke, Jake returns to the sleepy and peaceful town where his family once lived and learns of his father’s past – the story of his people, and the journey of a new-born species that strived to live in a world that used to behead and fry them for food.

It is, initially, funny and even ridiculous to see Jake throwing a fit about how his people had been killed, plucked naked, boiled, and fried for consumption. To me, it certainly was an amusing outburst, but the more I learned Elmer’s story, the more I began to see them less and less as chickens, and more and more as Jewish children herded into death camps, as “colored” people lynched by paranoid white supremacists, and even as prosecuted homosexuals.

Elmer’s story is not a story of a fowl. It is the story of a person who has undergone traumatic events in a world that reacts negatively to something – or someone – different. It is the story of a survivor who has lost family and friends in a judgmental world that seeks to eliminate any perceived danger that’s not even there. It is the story of a person who grew up and lived in a time where to even think that he has as much right as the next person to walk the streets is fatal.

Each scene is realistic and drawn with passion and every emotion bleeds into each line and shade. The bloody violence between man and chicken may sound ludicrous an idea, but it feels terrible and tragic in Alanguilan’s novel. The greatest strength of the story, however, lies in the fact that Alanguilan told the story through the perspective of a chicken – precisely because to us, Homo sapiens sapiens, a chicken being part of the human race is unbelievable and incomprehensible – and this is exactly how people thought before when they refused to let colored people sit in the same bench as the white people, when they drove Jewish people into a separate part of the city, or when native people were driven from their homes and made to slave away in dangerous conditions.

Elmer is every person in the world who has been discriminated against and made to feel inferior. Elmer is every person who overcame his violent past and lived in the present, and his son Jake is any one of us who learns tolerance and to accept a hopeful future, where we can believe that we are truly part of this world.

Nominee for Best New Graphic Album in 2011 and winner of the Best Asian Album award and Quai des Bulles in France, this graphic novel deserves all its praises. It is both inspiring and disturbing. It is certainly not to be mistaken as a children’s comic about talking chickens, though.

I will never regret having read this novel. I only regret that I hadn’t read it sooner.

Thank you. Now I want to read this.