Jonathan Mok: Can you tell me how this book came about?

Bijan Khezri: Writing is a personal journey. Three milestones stand out. First, following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the world, and Europe in particular, were filled with excitement. In 1992 the Maastricht Treaty followed, defining the roadmap for European Monetary Union. In fact, German unification set free a massive push towards European political integration. Europe will inspire the world as the 21st century economic and political powerhouse, the common belief was. Second, in May 2005, the voters of France and the Netherlands rejected in referenda the proposed European Constitution.

Voters across Europe were increasingly eager to seize any opportunity to express their frustration and disillusionment with European monetary and political integration. Voters did not vote so much against the Constitution but rejected a system of excessive bureaucracy that struggles to create jobs and serve citizens’ basic needs in public healthcare, education and transport. At the time the Wall Street Journal titled my opinion piece “At the End of an Age in Europe”. Indeed, an age where European integration was accepted as a worthy end in its own right had come to an end.

More and more Europeans started looking for job prospects outside their home countries and beyond the European Union. Third, in March 2007, I actively re-engaged with Dubai through my involvement in the art world. I reckoned that Dubai had emerged as a microcosm reuniting a newly emerging global generation. This generation has opted to exit their home-countries where entrepreneurship and job creation have often been suffocated by a sprawling tax and regulatory bureaucracy. This generation is less concerned with political rights. Loyalty is primarily towards their personal and economic advancement. I felt an Age, characterized by a blind obsession with democracy, was truly coming to an end. I was keen to pull all the dots together.

Jonathan: On pages 37-38, you write, “Democracy is the least evil of government systems, and possibly the best in terms of its ability to sustain continuity and peaceful succession in leadership. But democracy must reinvent itself and become more results-oriented, pragmatic and corporate in its governance approach.” What has gone wrong in the democratic system, in your opinion? What steps should politicians take to achieve the “reinvention” you suggest?

Bijan: Political parties are the foundation of modern democracy. But politicians’ obsession with career within a political party is largely to be held responsible for modern democracy’s decay. The lawmakers’ quality of independence and analysis underlying political judgment is likely to be clouded by the party politics that have been allowed to solely define one’s political existence and consciousness. And the importance of money in election campaigns has undermined democracy, too.

Lobbyists’ power is a serious threat to the notion of “people’s self-government”. Whilst the election of Barack Obama has somehow revived the meaning of the individual’s vote, we should not forget that it took Obama more than US$1bn to ascend to the presidency. The effectiveness of his leadership will ultimately be compromised by a complex web of interests that are not necessarily aligned with his first choices.

The current credit crisis offers a unique opportunity to not only question our economic, regulatory and fiscal structures. More importantly, we should question the process that generates the choices.

The role of the individual lawmaker must be redefined. Similar to Switzerland’s system, lawmakers should not be career politicians but practice a profession outside of parliament. This is likely to take the ‘glamour’ out of lawmaking and should re-emphasise efficiency and results. Every parliament should also include a certain number of lawmakers that have no historic or present affiliation with any one political party. Such mandate has the potential to reignite the electorate’s engagement in the political process. Modern media, blogging and social networking have substantially reduced the individual’s barriers and costs to entering politics but for the gate-keeping of political parties.

Election manifestos must become business plans – defined by principles and measured by performance benchmarks against spending. Once approved by the legislative, the executive must be fully empowered to execute with authority. Government spending must be capped as a percentage of gross national product for the governing period. During the governing period the legislative’s primary responsibility is to supervise the execution of the ‘business plan’ and ensure that ad-hoc policy making is in accordance with established principles and objectives.

Jonathan: On page 46, you argue that “…Pax Americana is likely to remain the dominant world order, despite all gloomy projection and a battery of costly US policies since the turn of the country. The United States is too big a market, too capitalistic a system and still too energetic and youthful in spirit, not to remain the world’s leading nation-at least for foreseeable generations.” What are the reasons for this analysis, as the United States is dealing with problems such as financial and trade deficits, wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and a financial tsunami?

Jonathan: On page 46, you argue that “…Pax Americana is likely to remain the dominant world order, despite all gloomy projection and a battery of costly US policies since the turn of the country. The United States is too big a market, too capitalistic a system and still too energetic and youthful in spirit, not to remain the world’s leading nation-at least for foreseeable generations.” What are the reasons for this analysis, as the United States is dealing with problems such as financial and trade deficits, wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and a financial tsunami?

Bijan: The United States, more than any other nation in modern history, has proven an enormous capacity to successfully reinvent itself. Americans have embraced change as a basic value. America is likely to re-emerge from the credit crisis first. This is not necessarily because its policies are superior.

In fact, in its desire to address economic imbalances here and now, America often overshoots in the wrong direction. Its military engagements are similarly marred. But overall, today a whole nation is supporting the effort to turn this economy around as quickly as possible.

Europe is plagued by self-denial. And more importantly, Europe is not acting with one voice. Economic nationalism is now likely to fragment what was meant to be a united economic powerhouse challenging the US. China is the closest and most credible challenger to the US. But then few truly trust the Chinese. Demographic trends, uncontrolled urban development, environmentally disastrous infrastructure projects and contaminated products from toys to food, will compromise, or delay, China’s future superpower status.

Jonathan: Let’s talk about Dubai. What has made the city unique in the Middle East, even in the world? In your opinion, which city would be Dubai’s greatest competitor?

Bijan: Historically, Dubai’s economic foundation was driven by low-taxation and a trading-friendly environment. Discontented Persians settled in Dubai in the 19th century to pursue their trading activities. Today, those families still represent some of Dubai’s leading trading companies.

Dubai’s principal economic activity was pearl-diving. Following the Great Depression in the 1930s and the introduction of cultured pearls from Japan, Dubai was bankrupt, faced with the challenge of survival. It is a spirit of “Daring the Improbable” that was born at this stage and that remained Dubai’s driving economic force until today. No other emerging city in the world has ever so uncompromisingly embraced and succeeded with the ethos “build and they will come”.

Dubai borrowed GBP 500,000 from Kuwait in 1958 to dredge the creek’s shallow waters for larger cargo ships. Today, Dubai is one of the world’s largest port operators competing head-to-head with Singapore. It is this spirit, combined with an extraordinary discipline and focus that allowed Dubai to grow beyond anyone’s imagination.

During the past five years, though, in a global environment of credit-fuelled growth, Dub was blinded by high-leverage opportunities. But to judge by Dubai’s short history, it is likely to manage the crisis.

Despite Dubai’s global status, it still remains very much a regional powerhouse. Singapore and Hong Kong are obvious city-state competitors. But the true competition is coming from regional players such as Qatar and Saudi Arabia, two countries that were inspired by Dubai’s strategic economic development to start with. Abu Dhabi is not competing with Dubai as they are too different in nature. Abu Dhabi has also no interest to see Dubai falling. However, Abu Dhabi is keen to leverage its financial muscle.

Jonathan: Most importantly, in what ways can Dubai withstand the aftermath of current financial crisis?

Bijan: There was a mistaken belief that you can sustainably drive a double-digit growth economy that is entirely dependent on the outside world investing and moving to Dubai. Too much speculative capital has been allowed to fuel the growth pattern in the past years. Discipline was blinded by the promises of high-leverage finance. Policy remedies to correct uncontrolled speculative growth, such as caps on rents, came too late.

The expatriate community is increasingly filled with anger. Unless you find a job within one month, you have to leave the country. There could be little loyalty left.

Then, Dubai will be less a victim of the credit crisis but of Generation Dubai moving on to other places. Above all, Dubai needs massive capital inflows to rebuilt confidence. When the UAE central bank subscribed to half of a $20bn five year bond program launched by the Dubai government this February, the tide that has been turning against Dubai lately, may itself be turning.

Dubai must implement changes at home and reach out to the rest of the world at the same time. If Dubai is serious about its long-term ambitions in financial services it should create, for example, a banking product that will allow leading mid-sized companies in the West, in particular in Germany, the UK and the US, to access funding. This could be a way to step into a vacuum that is being left vacant by London and New York. But more importantly, it could turn the world’s attention toward Dubai again.

Generation Dubai Review:

In his book, Peace Be Upon You: The Story of Muslim, Christian and Jewish Coexistence, American historian Zachary Karabell hailed Dubai as the best model of coexistence. He argued that the success of Dubai illustrated the possibility of how people can live peacefully when money, not religious dogma, is a dominant priority.

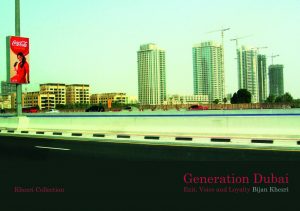

Now, corporate financier Bijan Khezri has emerged as another voice demonstrating why Dubai will be the model of co-existence while sharing his view on democracy and the clash of civilization in his essay-form book – Generation Dubai: Exit, Voice and Loyalty.

This is not a run-of-the-mill coffee-table book.

The list of bibliography and quotations includes works by Jacques Bauman, E.H.Gombrich and Oswald Spengler. Photos of Khezri’s art collection, including Charles Avery’s Plane of the Gods and Ridable, added further flair.

I sometimes felt that Khezri’s voice was not entirely certain when he spoke about increasing mistrust of politicians among the general public in Europe and the United States. Yet the fact that the public believes that its own power has been gradually taken away by parliaments and lobbyists seems to be a foregone conclusion. As Hannah Arhedt argued seven decades ago, the only political system that can truly improve public’s well-being was enlightened despotism. In today’s language, it means benevolent dictatorship.

Khezri spoke of how he did not find Chinese and Russian authoritarian systems to be suitable ruling models, for example. I wasn’t sure, however, what he considered to be a suitable ruling model overall.

The challenges to Dubai’s future also needed further exploration. How can the city become more green in the age of global warming, for example? How can a balance between local values and foreign values be established?

The recent case of the British couple Vince Acors and Michelle Palmers, who were convicted of having sex in a public place, was not just about a clash of cultures. Such public displays are also forbidden in the Europe and the United States. Yet, the Western media and newspapers, as Hala Gorani of CNN lamented, reported that the arrest of the couple was the enforcement of a conservative code of conduct, alien to Western values. Discussion of media bias against Dubai would have been particularly interesting within the context of Khezri’s work.

Khezri’s honest look at how the desire for political freedom is often outweighed by the desire to lead a stable and prosperous life is something to be commended. Of course, how the current economic crisis will truly impact the chances for prosperity in Dubai remains to be seen.