In mid May 2019, the centre right Liberal National Coalition defeated the centre left Labor Party in a general election held in Australia. It was a win that surprised everyone, even the governing Coalition. In his victory speech in Sydney that election night, Prime Minister Scott Morrison called it “a miracle”.

It was an apt turn of phrase for the church going Prime Minister but that night, Scott Morrison may not have been as surprised at the result as everyone else was – most notably his opponents.

In the lead up to the election, the politicians, the media, and almost everyone with an opinion predicted a Labour win. Sports betting agencies, usually better predictors of elections than the opinion polls, had Labor at short $1.16 odds. One betting agency was so confident it paid out on Labor bets three days early, leaving it with egg on its face and having also to pay out punters who had backed the Coalition at much longer odds.

So how did an incumbent Coalition government that had held office for six years and churned through three Prime Ministers in that time and was seen by many to be stale, bereft of ideas, and out of touch with the zeitgeist, win? And how did the Labor Party lose the unloseable election? Labour had won every opinion running for the last two years, had a raft of fresh policy ideas, and seemed an unstoppable force.

“A jubilant Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison vowed Sunday to get straight back to work after a shock election victory by his conservative government that has left bewildered voters wondering how they were taken by surprise”. Washington Post, 19 May 2019

The answer in hindsight is glaringly obvious. The interesting issue is why so few people picked up on it prior to the election.

Australia has three tiers of government; federal, state, and local. The federal government takes care of things like defence and national security. The state government take care of matters such as public transport and schooling. Local government empties the street rubbish bins and maintains local streets. This election concerned the federal government. Voting is compulsory in Australia and that tends to keep the two major parties reasonably centrist. Parties towards the outliers of the political spectrum, the Greens on the left and the Nationalists on the right, tend to pick up far fewer votes.

In the Federal Parliament there are two houses, the House of Representatives and the Senate. The House of Representatives has 151 members, each representing the 151 electorates throughout Australia. The political party with a majority (or alternatively a minority but enjoys the support of enough Independent members to function as a majority) governs. Prime Ministers are not elected directly (as in the US Presidential model) but are the leaders of the governing political party. The Senate comprises 76 Senators. Its role is to pass legislation. The government of the day doesn’t have to have control of the Senate to govern but as governments worldwide have found, it certainly helps.

The Coalition, which was governing one seat short of a majority prior to the election, astounded everyone and increased the number of seats they hold to 78 and is now able to govern with a majority.

“Polls suggest Labor could make a net gain of 12 seats, giving it 81 MPs in the 151-seat parliament.” SBS News. Early on election day. 18 May 2019.

Australia was colonised by England in 1788 to serve as a penal colony for its petticoat thieves and forgers. In 231 years it has come a long way. With a population of 25 million, it has become one of the richest countries in the world. The average Aussie enjoys a pretty comfortable and pleasant life which, when push came to shove on election day, they didn’t really want to risk.

The Labor Party was founded off the back of the trade union movement back in the 1890s. It has long been the party of the workers and the working class. It still retains strong union ties. Bill Shorten who took the Labor Party to the May election was a union official in his pre political life. Labor has historically stood for improved working conditions, decent incomes, and keeping the bosses honest. No one has much quibble with that.

The Coalition is comprised of the Liberal and National Parties. The National Party was formerly the Country Party with a conservative, rural constituency. The Liberal Party, the larger of the two parties was formed in the early 1940s by Robert Menzies (who went on to be Australia’s longest serving Prime Minister) as his response to his perceived socialist trends in the then Australian government. The party, while recognising the role of the state in the economy, was a big fan of private enterprise and a solid work ethic.

Between them, these two groups and their incarnations have won every federal election since Australia gained independence in 1901.

In the 2019 election the Coalition campaigned on responsible economic management (it has just delivered a budget surplus), income tax cuts, strong borders, and a continuation of business as usual. It was hardly revolutionary. Labor campaigned on income redistribution, climate change, the environment, and tax increases for the wealthy (defined as people earning more than AUD$84,000 – hardly wealthy in Australia). In contrast to the Coalition manifesto, what Bill Shorten and his Labor team proposed was an agenda for change.

The modern Labor Party has long courted several constituencies in addition to its working class base. Its interest in social issues resonates with traditional Green voters and those affluent enough to take an active interest in social justice. Labor’s fatal error was to court these voters at the expense of their traditional base.

In 2019, Labor’s climate change and environmental manifesto was music to the ears of the primarily urban Greens and affluent left. Its traditional voter base, the workers, were more concerned about jobs and the cost of living.

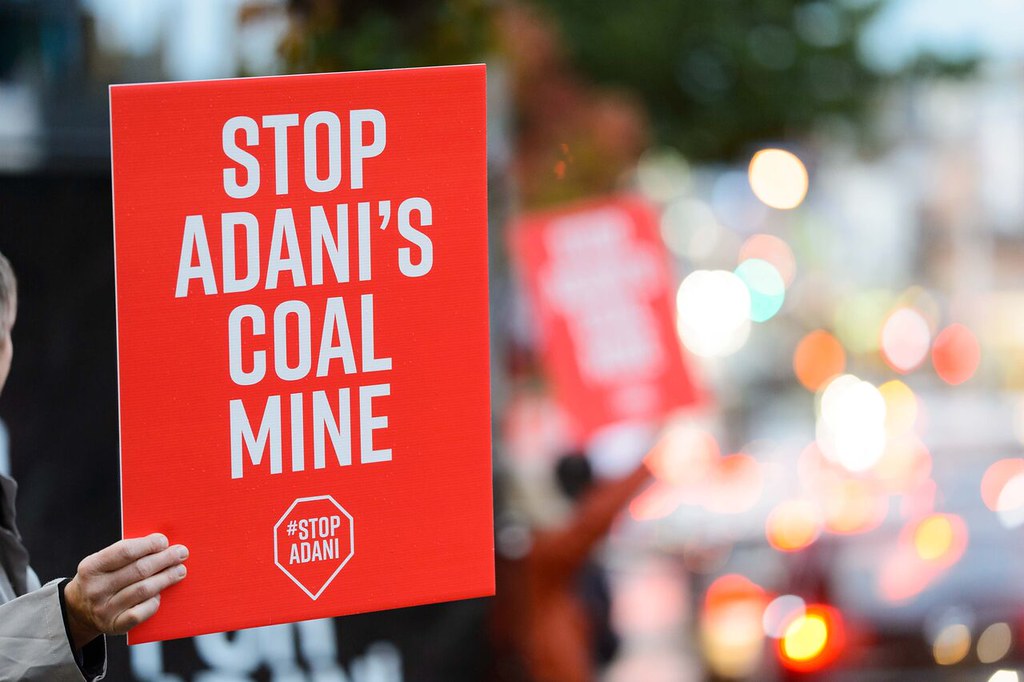

Labor ended up getting hit hard because of several policies that were unacceptable to the majority of the Australian population, but one issue captures several of the missteps Labor made. That issue was a proposed coal mine in Queensland called Adani.

The 2019 election turned out to be won and lost in the resource rich state of Queensland on Australia’s north east coast. Australia is the world’s largest coal exporter and the Queensland’s coal mines help drive the Australian economy. The mine workers and all the workers in allied industries are a natural Labor constituency.

The south east corner of Queensland is heavily urbanised while the remainder of the state is regional or rural. In the south east of the state is Brisbane, the capital. Labor is in power in Queensland at the state government level. The Premier, Annastacia Palaszczuk, is regarded as an ineffective centrist who is outgunned and outnumbered by deputy Jackie Trad and her left faction within Queensland Labor.

The State Labor Government in Brisbane and in particular Jackie Trad, are anti-coal. They have been delaying approving the Adani coal mine, one thousand miles away in regional Queensland. This mine represented jobs and income for thousand of Queenslanders and their families, the benefits of which would flow into local towns and cities, and the royalties the mines pay effectively underwrite the Queensland state economy. The Adani coal was to go to India where it was going to provide cheap energy for Indians, the vast majority of whom could not begin to fathom the living standards most Australians enjoy.

One of Bill Shorten’s fatal mistakes was to play both sides of the street on Adani. He told his Green anti Adani constituencies in Melbourne that Adani would go ahead over his dead body. Two thousand kilometres away in Queensland, he told his worker constituencies who backed the mine that he would see what he could do. The dissonance was noted.

A tradesperson (or tradie in Australian parlance) in the Queensland port town of Gladstone, a man who is a direct beneficiary of a mine like Adani, asked Bill Shorten if he would be giving any tax breaks to workers like him on AUD$250,000 (that’s not a misprint) plus salaries. Labor’s well publicised policy was to raise income tax for people earning more than AUD$84,000 but Shorten looked this tradie in the eye, with media in attendance, lied outright and said that was something he would look at doing.

Down within the quinoa circles of inner city Melbourne and Sydney, an idea was born to take an anti Adani protest convoy up to the central Queensland mining town to spread the anti Adani message. The convoy was to be lead by Bob Brown, former leader of the Australian Greens who was a decent environmental warrior in his time, once going to jail for his troubles.

This gauche crowd, the majority of whom leave a carbon footprint fifty miles wide in their everyday lives, drove their fossil fueled vehicles up into central Queensland to take the message to the slack jawed ignorant miners and their kinfolk. The reception when they drove into the small town of Clermont (pop.3000) was one of the defining points of the election campaign. Shopkeepers refused to serve them, publicans closed their doors, politicians on the make flew in on chartered jets, and those anti Adani protesters, those stalwarts of the left, were said to have delivered more Queensland votes to the Coalition than anything else in the election campaign.

The Coalition won 23 out of the 30 electorates in Queensland. On election night, as the magnitude of Labor’s shock loss began to be apparent, several Coalition politicians thanked Bob Brown and those anti Adani protesters for handing them Queensland and the election.

“Thank you Bob Brown is all I can say”. Michelle Landry, Coalition MP, 18 May 2019.

Scott Morrison and the Coalition were wise enough to let the Adani boil fester for Labor. When asked whether he supported the mine, Morrison said yes, he supported jobs and growth for Australia. An adroit non answer that directly contradicted Shorten’s anti job message in job hungry Queensland.

Shorten and Labor fell prey to the chattering of the chattering classes. They do make a lot of noise, what with their Twitter accounts, media columns, Insta profiles, TV guest appearances and Youtube channels. What’s overlooked is that, they are basically talking to each other and in their echo chamber, the only voices they can hear are their own. All in accord.

But quietly in the rest of Australia, where life is good but we all have to get up in the morning and go to work, there was a contempt brewing for the hubris and confidence of the pro Labor chattering crew. Nobody likes been told that the environment is more important than your job, that you’re rich cause you earn more than eighty four thousand a year and so good for a tax increase, that your efforts to build a better life and be self reliant are an opportunity for a money grab for the government. Under the slogans and false promises and slick social media, this was the message that Labor was pumping out in an effort to please the echo chamber.

The mainstream media, on the back of the opinion polls and most of its journos, left or right, who were fully subscribed members of the antipodean chattering class were expecting a Labor win and this message, day after day, was send down to readers, listeners and viewers.

But Scott Morrison and his Coalition, it turns out, were cautiously optimistic. The Coalition’s message wasn’t sexy but it was targeted right at the people Labor was either ignoring – the middle class, or taking for granted – those union affiliated workers out in the mines and factories and industrial plants. These people made up the bulk of the Australian voting public. Most of them hold Twitter in contempt and don’t read up on the opinion polls. The feedback the Coalition were getting in the weeks prior to the election gave them grounds for hope. But they keep working. On the final day of the election campaign, Scott Morrison campaigned up in coal country in Queensland, in New South Wales, and finally in Tasmania.

Bill Shorten was so confident of a win he ceased campaigning and went to the pub in Melbourne for a few drinks that last afternoon.

That old conservative warhorse, Robert Menzies, gave a radio speech preceding the formation of the Liberal Party in in 1942.

“The time has come to say something of the forgotten class, the middle class who, properly regarded, represent the backbone of this country … who were neither rich or powerful … the lifters not the leaners” Robert Menzies. 22 May 1942

Shorten lost the election because he forgot the backbone and focused on the loud shiny bits.

Morrison and the Coalition quietly courted that backbone; the tradies, the small business owners and the all workers with their side hustles who are just trying to get ahead in life – the forgotten class. Just as relevant in 2019 and 1942. In their quiet unassuming way they coalesced in unison on 18 May 2019 to kick the Australian Labor Party out of the park.

Photo: Stop Adani