Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko is expected to easily win the presidential election scheduled for August 9, especially now that all key opposition candidates are behind bars. Last week, Belarusian authorities arrested Viktor Babariko, former head of the local unit of Russia’s Gazprombank and Lukashenko’s main rival, which sparked protests all over the country. Could this lead to a regime change in Minsk?

The opposition in Belarus can come to power only if it manages to overthrow Lukashenko through violent protests, which is at this point not very probable as the country’s leader still has a firm control over the KGB and other security structures. It is worth noting that his son Viktor is a member of the country’s Security Council, and Lukashenko recently dismissed the Belarusian government and appointed people who are expected to be more loyal to him. The opposition has no chance to come to power through elections, as the election process is firmly controlled by Lukashenko. The opposition candidates have no access to mainstream media, and the vote counting is controlled by the Election Commission that is, naturally, loyal to Lukashenko. In other words, since the elections in Belarus are from fair – which is also the case in most countries in the world, including those that claim to follow democratic procedures – the authorities can simply “draw” a very small percentage of votes to Babariko, or any other opposition figure, at the end of the election day. There is virtually nothing the opposition can do about that, except to stage mass protests. However, Lukashenko seems to be quite ready for that.

After Babariko was arrested on June 18, hundreds of people came outside to protest and dozens were detained. Last month, Belarusian police arrested a popular vlogger Syarhey Tsikhanouski and that way prevented him from running the presidential election. Nikolai Statkevich, who was a presidential candidate in the 2010 election, was also jailed, and last week Yuri Gubarevich, the head of the For Freedom movement, was sentenced to 15 days in prison for “running a mass event”. Previously, in an attempt to put pressure on Viktor Babariko, Belarusian security forces raided the local unit of Russia’s Gazprombank, which was until recently headed by the opposition politician. Babariko was accused of siphoning $430 million US out of Belarus in money-laundering schemes. That way, Lukashenko is trying to discredit his rival in the eyes of potential voters.

“I want him to get nominated so that he comes and tells everyone where his property in Cyprus came from, how he managed to acquire it in ‘Lukashenko’s dictatorship’. He should tell Belarusians all of this. Let them decide afterwards. But we will not make him a prisoner of conscience”, said Lukashenko, according to BelTA news agency.

Even though Babariko managed to collect more than 400 thousand signatures for the presidential nomination, it is unlikely that he would win the election even it was not rigged. The main body of demonstrators all over Belarus are students and young people, who traditionally take part in anti-government rallies. They make up the majority of Babariko’s voters. Lukashenko, on the other hand, can count on the vast majority of two million pensioners, as well as the rural population. The median age in Belarus is 40.3 years, which means that for authorities there is no danger of a youth bulge. Still, Lukashenko, as an experienced politician who has been running the country since 1994, does not want to risk it. He openly said that if he acts democratically, he will lose the country and be “cursed”.

“If I behave democratically, I will show that I am fluffy, and then I have a chance of losing the country entirely. I will be cursed and no one will forgive me for the destruction of Belarus”, said Lukashenko accusing the opposition of pushing him towards a “solution by force”.

“For now, I am asking and warning: Don’t do it, don’t force the authorities to move to measures of reaction, don’t push us to that. I will preserve this country no matter what it costs me.”

Unlike former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych, who was overthrown by pro-Western protesters in 2014, Lukashenko seems to be determined not to allow any Ukrainian-style demonstrations in Belarus. There is no doubt that he would fight until the end. The problem for the Belarusian opposition, on the other hand, is the fact that it is not backed by the West in the same way Ukrainian anti-Yanukovych forces were supported. Apart from harsh threats, there is not much the West can do against Lukashenko. If the European Union and the United States impose severe sanctions on Belarus, Lukashenko will have to turn eastward. However, in that case he will have to make some serious concessions to Russia. Moscow has already demonstrated that it is not willing to keep providing cheap energy to its only ally in Europe, which is why relations between the two countries are currently at a dead end.

For both the West and Russia, energy-dependent Belarus is merely as a transit country and a robbery target. Over the past 26 years, Lukashenko has managed to save the vast majority of Belarusian state-owned enterprises from Russian oligarchs and Western corporations who aimed to privatize them. In the foreseeable future, however, he will likely have to start selling some successful companies in order to fill budget holes. That could be just the beginning of the gradual transformation of the Belarusian political system. In any case, the future of Belarus will depend not on the election results, but on lucrative geopolitical deals that the Russian elite and its “dear Western partners” will make.

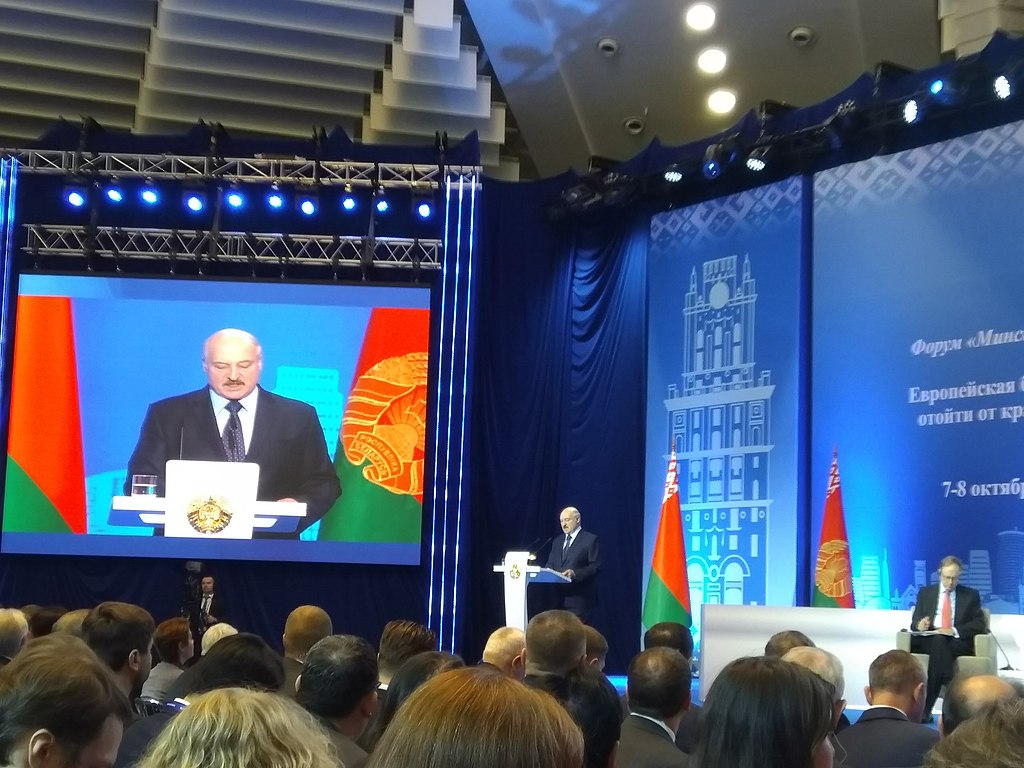

Image credit: Miłosz Pieńkowski