For the past week and a half or so, I have been dealing with a shoulder/back injury that has cut my productivity down to the nub. I don’t know how I injured myself, so I suspect that this muscle pull occurred while I was asleep. If I move my arm or neck a certain way, I get a weird twisting pain that shoots into my fingers. In addition to the chronic pain and fatigue that I deal with from fibromyalgia, this “new” pain is also not fun to deal with on a constant basis, and although the shoulder/neck injury has gotten better over the past few days—primarily because I have a lot of heating pads and use a couple of them at the same time—it has also made me slow down way more than usual.

If I move the wrong way, the pain starts to feel like a huge tentacle that has wrapped its way around the muscles in my left arm and shoulder, and might burst out of my body. It’s like the world’s least believable horror movie, complete with SyFy Channel-level production values. As you might guess, having this kind of acute pain on top of chronic pain is not advantageous when one’s career is freelance writing and when that person is working on a deadline.

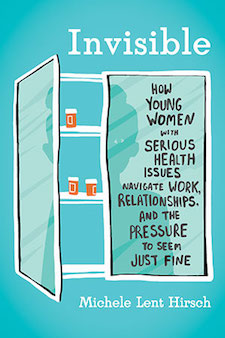

I mention all of this to contextualize my reaction(s) to writer Michele Lent Hirsch’s new book Invisible: How Young Women With Serious Illness Manage Work, Relationships, and the Pressure to Seem Just Fine. Hirsch—a writer on health issues whose work has appeared on The Atlantic and the Guardian, among other sites—has written a compelling and necessary book that will appeal to a wide audience. That “appealing to a wide audience” part is especially important, because although young women with chronic illness who write about their experiences publicly have been around for a long time (I’m one of them), Hirsch’s book is a solid introduction to the many issues facing young women who deal with serious health issues.

One thing that greatly contributes to Invisible’s success is Hirsch’s willingness to share (sometimes gruesome) parts of her own experiences with multiple health issues, including cancer and anaphylaxis—she’s not writing about young women with chronic illness as if they are things to be studied, but she writes as one of those young women. It’s obvious that she understands the myriad challenges of having health issues at a young age from the inside, and her writing is both easy to follow and absorbing.

Impressively, she interviews women with a wide variety of health issues—among them mental health issues, HIV, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, and Crohn’s disease—and compellingly interweave their stories and experiences with her own. The diversity of her interviewees is laudable as well; she interviews women from many different racial and economic backgrounds, as well as trans women and gender nonconforming people—many of these people are, arguably, made further invisible because of their identities. Certain segments of the chronic illness or “spoonie” movement online, for example, look like they are comprised mostly of young white women—at least at first glance—but Hirsch’s choice of interviewees reminds us that some people who are marginalized due to multiple factors also deal with life-changing health issues.

Impressively, she interviews women with a wide variety of health issues—among them mental health issues, HIV, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, and Crohn’s disease—and compellingly interweave their stories and experiences with her own. The diversity of her interviewees is laudable as well; she interviews women from many different racial and economic backgrounds, as well as trans women and gender nonconforming people—many of these people are, arguably, made further invisible because of their identities. Certain segments of the chronic illness or “spoonie” movement online, for example, look like they are comprised mostly of young white women—at least at first glance—but Hirsch’s choice of interviewees reminds us that some people who are marginalized due to multiple factors also deal with life-changing health issues.

As someone who has also dealt with terrible doctors, getting randomly cursed out by older people because I use a cane, and asked to my face if I am “too young” to have fibromyalgia (by an older woman with the same condition, no less), I found myself nodding along with much of this book. I can assure you that the nodding was not great for my neck/shoulder, but Invisible also made me feel less weird about my own experiences with chronic health issues as a relatively young person. If you’re young and have a chronic illness, chronic pain, or disability of some sort, you should definitely read this book. If you don’t deal with any of those things—or know someone who does—you should absolutely read this book.

Photo: Roco Julie/Creative Commons