“Living is an adventure and a challenge…If anybody wants to keep creating they have to be about change.” Opening with the words of the great jazz musician himself, the tone is set for Stanley Nelson’s latest documentary Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool. Though the film relies heavily on predictable archival footage, and straightforward talking head interviews with critics and historians (it’s for public television’s “American Masters” series after all), Nelson nevertheless manages to provide an informative glimpse into the life of an unconventional artist, one filled with real surprises at every turn. (All moved quickly along with the help of a mind-blowing soundtrack, naturally.)

Beginning with Davis’s unusual upbringing in the Jim Crow South – as a wealthy black kid. Unlike the overwhelming majority of African-Americans in the pre-civil rights era, Davis’s father was actually well off, working as a dentist and a farmer. The son stood apart from the pack as well, considered both a “genius and weird” according to one childhood friend. And the charmed life continued right through adolescence. At the tender age of eighteen, Davis got the chance to sit in with Billy Eckstine’s band when their trumpeter fell ill – which is how he met “Dizzy and Bird.” And became convinced that NYC was the place to be.

For 52nd Street in the 1940s was lined up and down with jazz clubs. “That shit was so good it was scary,” according to Davis. He then enrolled in Julliard (yet another unconventional twist). “Be-bop musicians were like rocket scientists,” is how the writer Greg Tate puts it about Charlie Parker and his fellow pioneering musicians. While Quincy Jones noted that Davis, for his part, desired “to be just like Stravinsky.” Hence, the move to Europe – where the future legend found both artistic freedom and a refreshing lack of racism in Paris. There he met Picasso and Sartre, and fell in love with a French actress (“love” being the reason he didn’t marry her).

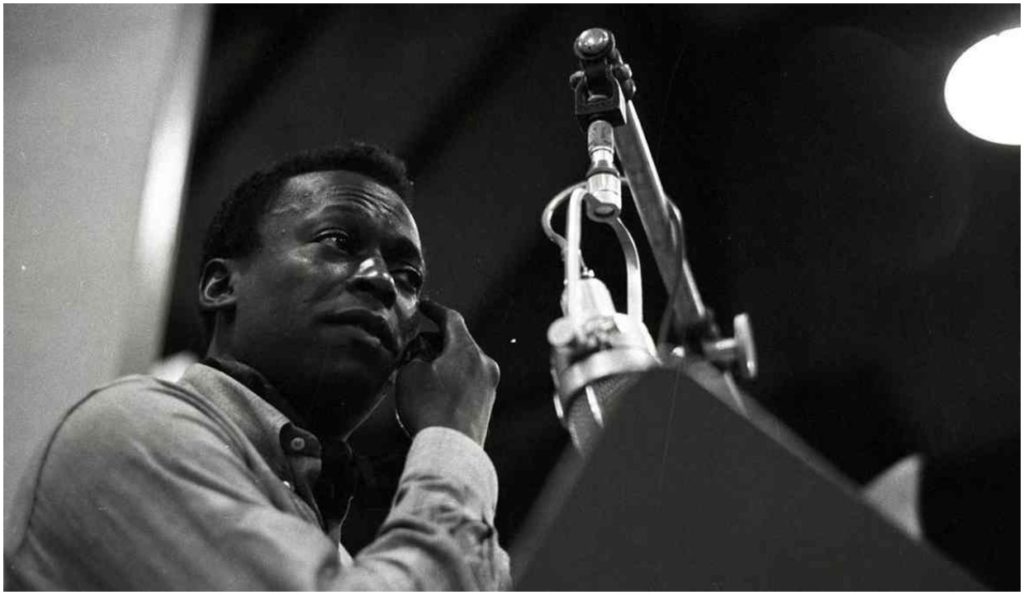

It was only when Davis went back to the racist US that depression hit – and a heroin habit followed to ease the pain. Even so, a fellow musician described the trumpeter’s sound as “a stone skipping across a pond.” Back in France Davis improvised the soundtrack to Louis Malle’s Elevator to the Gallows, but ultimately returned to the States to continue his jazz journey, forming a group that would give “Coltrane the space to become who he was,” as one talking head explained. It was during this time that Davis, ever the boundary breaker, “turned his dark skin into an asset – something cool.”

For “Miles didn’t have to please anyone but Miles,” a friend emphasized. When Davis left Prestige for Columbia (the “Tiffany of music labels,” as one historian noted) it wasn’t for financial enrichment, but because Columbia had the budget to realize his artistic dreams. And even at the new studio Davis was uncompromising, demanding that his black wife be on his album cover (and not the white women Columbia preferred). One of his bandmates described every night during that period as “going to a laboratory with Miles as head chemist.” They were tasked to “create a dangerous mix.” Indeed, Davis basically paid his musicians to experiment onstage in front of every audience.

“It wasn’t just a comeback of an artist – it was a comeback of a human being,” is how Davis’s manager summed up the legend’s late-in-life resurrection. After putting down the horn for years Davis not only returned musically in full force – but also took up painting. And since he’d always played with young musicians, the rebirth even included sitting in on sessions with Prince. Davis’s son disclosed that his dad never once talked about his old records – never even kept them in the house – forever solely focused on what was being created in the here and now. Becoming emotional, Quincy Jones reflected on convincing his old friend to play the Montreux Jazz Festival, and a moment when Davis made his “soul smile.” Davis, sick at the time, said that punishment is not not getting what you want. It’s getting what you want and there’s no time left.