Since the trailers for the next Star Trek series, Star Trek: Discovery, hit the Internet, I’ve been transfixed. Frankly, I’ve been giddy.

To cut to what Twitter, critics, bloggers, and Trekkies have been circling around: the captain and the first officer are women of color. Specifically a Chinese-Malaysian woman, Michelle Yeoh as Captain Philippa Georgiou, and a black woman, Sonequa Martin-Green as First Officer Michael Burnham.

Do you hear that? That’s the sound of long-suffering cis white fan-bros getting their typing fingers in a twist over the casting.

Such “fans” of Star Trek have called the cast (which is still 69 percent white) part of a “feminist” and “SJW” enacted “white genocide”. Some even had the audacity to complain that, as the largest Star Trek fan group, white men have the right to majority representation in the main cast; as loyal fans they deserve to see themselves represented.

Eye-roll – engage.

The fury is too predictable, boring, and ugly to give more word count to.

But the casting of Michelle Yeoh not only stokes the ire of fanboys; it also fans the flames of the ongoing fight for Asian and Asian-American representation in American media.

In recent memory – maybe any memory of mainstream American film or television – casting a person of Asian identity in a non-martial arts leading role, in an action film or series, is nearly unheard of (Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. is one exception…mostly). Dr. Strange, Ghost in the Shell, Iron Fist – all are recent examples where Asian actors were passed over in favor of more “bankable” white stars. Regardless of how the source material originally envisioned characters or, in the case of Iron Fist, how it could have avoided orientalist traps, the creators couldn’t bear to have Asian leads.

Why is Hollywood so averse to Asians?

The statement that there “aren’t any Asian movie stars” is another boring and predictable argument. Hollywood makes movie stars; very few show up at its doorstep guaranteeing money in the bank. The biz tells the public who to swoon over, who to pay to see.

Alan Yang, a former writer for Parks and Recreation and a co-creator of Master of None said in The Hollywood Reporter regarding taking risks on talent, “I understand the argument that the business is risk-averse, but that’s just an excuse to be cowardly. [Hollywood] cast Chris Pratt in Guardians of the Galaxy and Jurassic World. He wasn’t a movie star until they put him in those movies. For people who are making decisions, you have to take that risk.”

There is also the tired argument that movies with Asian leads fail. Full stop. But then you get into that “damned if you do” territory of, if you don’t cast Asian actors as leads in major movies, then how do you know that their movies invariably fail? What about the Harold & Kumar movies? What about The Joy Luck Club? Admittedly, there are few to point to, but the answer to why that is just circles back around to the initial question.

Of course we all know that movies with white leads never fail.

And how could we forget the argument that American audiences don’t want to see Asian lead actors in their movies. They – the Asians – aren’t relatable to a wide American audience. To that I say: you dug your own hole, Hollywood.

Asians are the largest growing racial group in the US, with over 21 million residents. Over 21 million residents who I bet wouldn’t mind seeing people like them portrayed as more than nerds and IT guys. Add to that an increasingly vocal outrage amongst non-Asian people over the whitewashing of films that should have starred actors of Asian descent, and the idea that Americans can’t handle Asians in film is not only antiquated but is rooted in racism. Those roots, that Hollywood and the media clings to, that stops execs from being able to fathom Asian leads in action films – or any major release films for that matter – were planted and cultivated in the good ol’ U.S. of A.

Under the weight of the “model minority” myth, Asia-Americans must now dig themselves out from how America has historically cast them.

In an attempt to bolster relations with China in an alliance against the Japan, the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943 and Chinese-Americans went from being feared and reviled as the antithesis of the American way of life, to being promoted as model citizens or the “model minority”.

Called “law-abiding, peace-loving, courteous people living quietly among us,” it was in America’s best interest to change the image of Chinese-Americans. The media of the 1950s and ’60s spread this idea of model minority far and wide, portraying Chinese-Americans (newly allowed citizenship after decades of being barred) as industrious, docile, and submissive.

This was a brand of Chinese that white Americans could approve of, feel comfortable with, but still dominate. Make no mistake, the model minority myth was not, and is not acceptance. It is another tactic of oppression.

For many years, especially during the internment of the Japanese and the civil rights movement, the Chinese as the “model minorities” were held up as examples used against black and Japanese-Americans. The narrative was that the Chinese had no help from America, yet they are succeeding – why can’t you?

Within that idea of model minority, Chinese-American men were depicted as good worker-bees, polite, and male but not “masculine” in the rugged, American ideal. Women were viewed as both demurely obedient and sexually aggressive. Movies like The World of Suzie Wong (1960) fed the cultural appetite for the sweet, sassy, wide-eyed prostitute character in need of saving by a real (white) man.

Chinese women were both the China doll and the dragon lady. Men were sexless wimps.

Model minority children were famously studious and high-achieving (supposedly), with Chinese families being held up as the epitome of conservative ideals due to their, disciplined “Confucian” backgrounds.

And because of the American habit of lumping similar cultures and peoples into one blanket term, the model minority stereotype that was created for Chinese-Americans came to encompass all “Asians” in America. Despite the vastly different immigrant experiences, demographics, and struggles of all the different Asian ethnicities in America (including Pacific Islanders), the idea of model minority in mainstream culture stretched to cover anyone in the spectrum of “yellow” to “brown”.

With such a pervasive stereotype, one that arguably has as strong an influence on the oppressors as well as the oppressed, it’s no wonder that Hollywood doesn’t think to cast Asian or Asian-American actors as heroic leads. Heroes in American media are daring, outspoken, brazen, sexy. That goes against everything the model minority is characterized as.

For the latter half of the 20th century, and a good part of the 21st century, Asians have not been thought of as leaders or fighters, but as non-intrusive sidekicks. While more Asian actors are being seen in film and television, they are still largely unable to break beyond supporting or “token” roles. Beyond skin color, beyond her accent or “broken English” as some of the Star Trek bros lamented, how can a timid Asian woman be the captain of a star ship? How can an Asian woman helm a revered American institution like Star Trek?

Within the stereotype of the model minority, how can the hero and the Asian be resolved?

With the recent awareness of whitewashing in major films, and the vocal anger from the Asian-American community, some continue to be surprised that the model minority speaks up. Not just speaks up, but demands representation.

But the narrative that the media constructed continues to eat its own tail. It’s all so circular. Just to be clear, let’s recap the circle:

The media – writers, artists, filmmakers, advertisers – perpetuated the stereotype of the model minority, the obedient Asian “other” in America. The myth of the model minority took hold, and both white and Asian-Americans bought into it, lived it. When it was convenient, the boundaries of model minority propriety could be stretched to include the dragon lady or mystical martial arts master in film and television, but portraying their Asians submissive was more within mainstream American interests. Asian-Americans tended to succeed if they colored within the lines of the stereotype.

Eventually, overt racial tensions began to ease, and Asian-Americans started asking for equality, more accurate representation in the media, leading roles. But those at the top of the media food chain said no. No, because that’s not how Asians are; that’s not how America sees Asians; and because of these things, a movie cannot financially succeed with an Asian lead.

But why aren’t Asians bankable? Because they are the model minority. And what is the model minority? A myth perpetuated by…etc.

Can the circle be unbroken? I think so. I hope so.

With shows like Star Trek: Discovery willing to pave the way, and movies like the upcoming Crazy Rich Asians (a Warner Bros. produced romantic comedy with an all Asian cast), perhaps minds will begin to change. But those in the trenches fighting for fair Asian casting are certainly facing an uphill battle. Not only are they fighting against the financial fears of Hollywood executives, but more than that the decades of ingrained American racism that created the idea of the “Asian-American”.

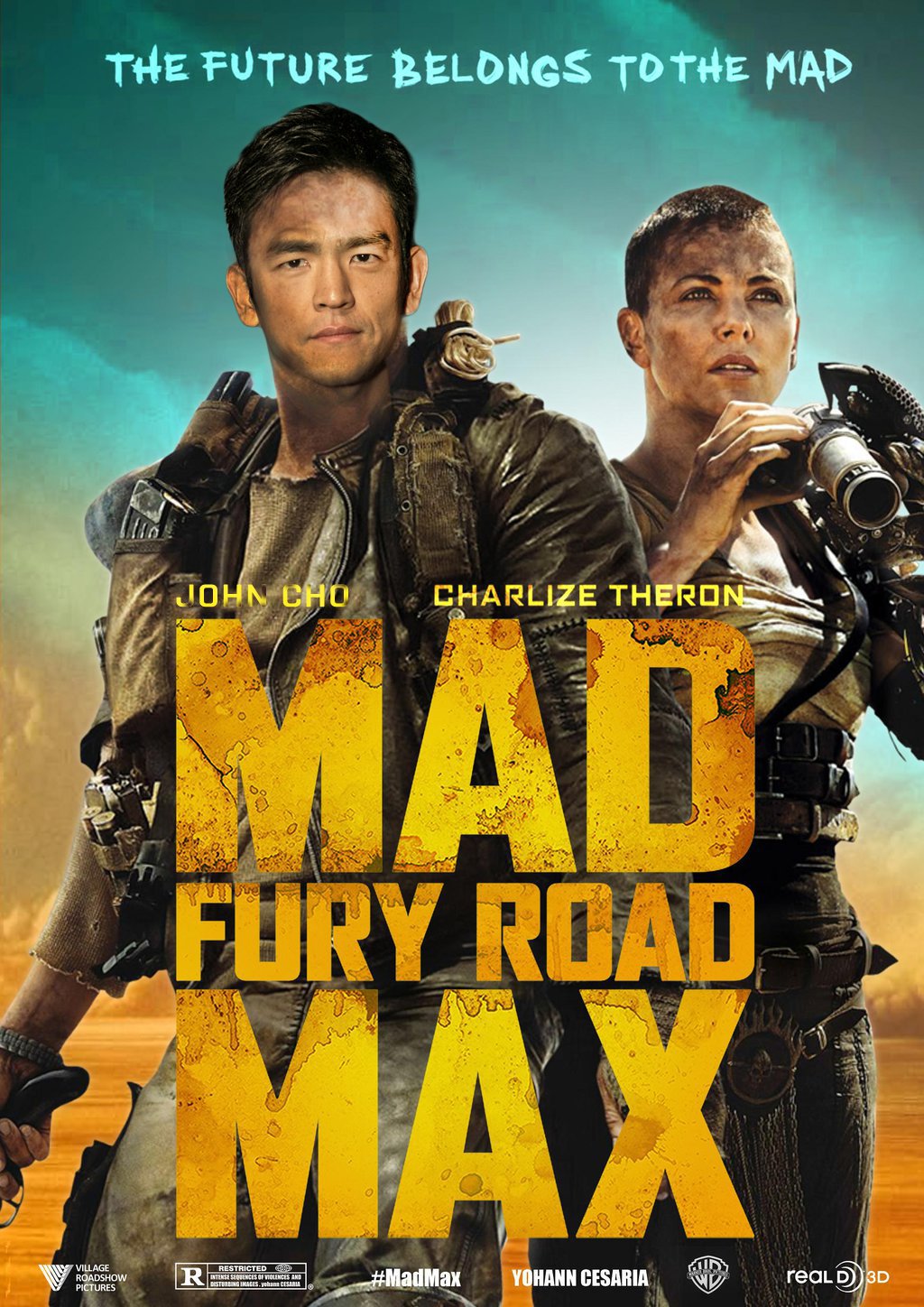

Featured image via Twitter