For a long time, I had planned to start busking for some extra cash. When I moved from Rome to Melbourne I felt it was the right time. In Australia, I wouldn’t run the risk of having one of my former art academy teachers run into me and give me a look of disapproval. Strangely enough, even in a bohemian environment like the art academy, many people still consider busking as the last resort for an artist. While I vehemently disagree, that judgment still kept me from busking in Rome. “Well, worst case scenario we will end up painting portraits of people in Piazza Navona”, my friends used to say snarkily.

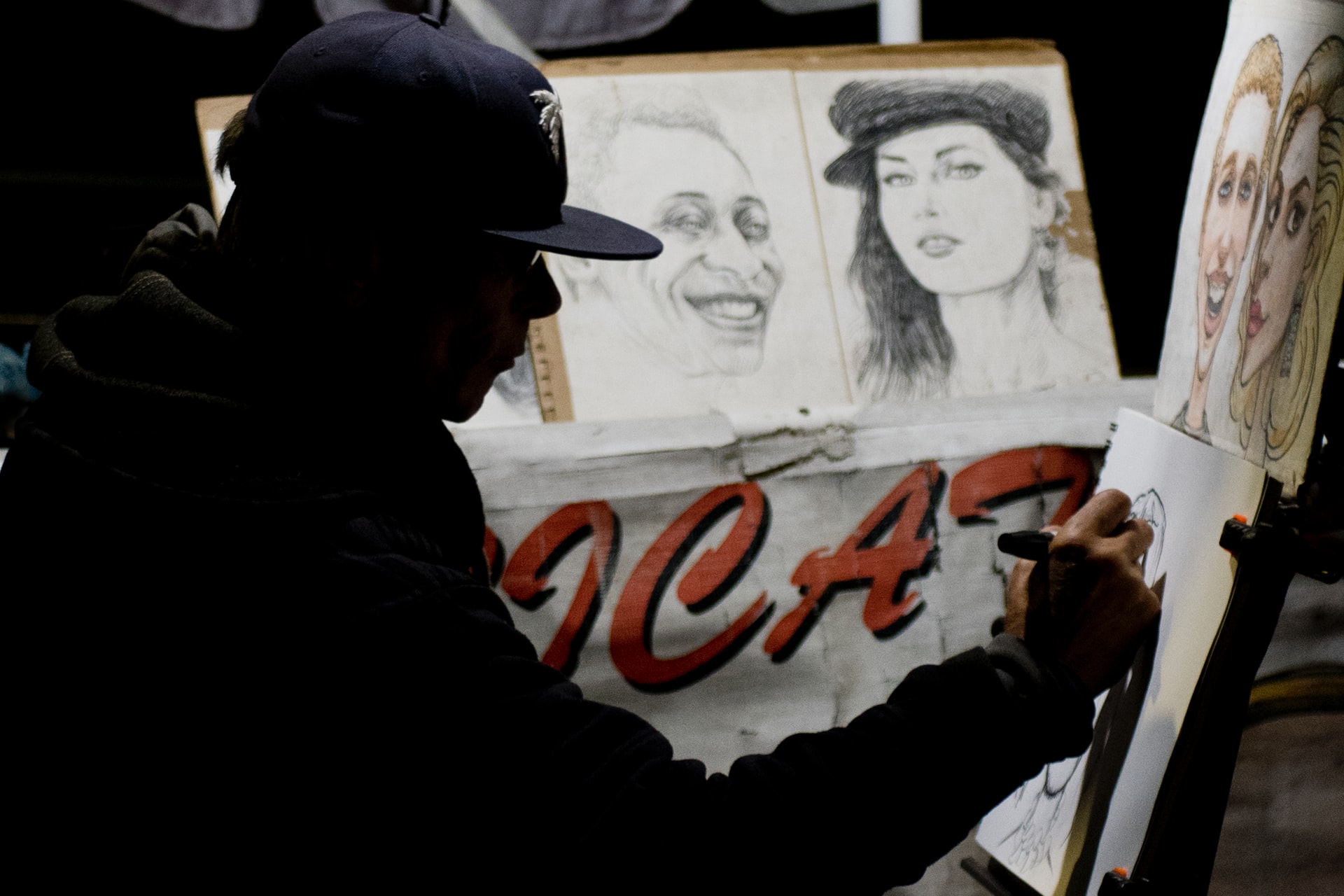

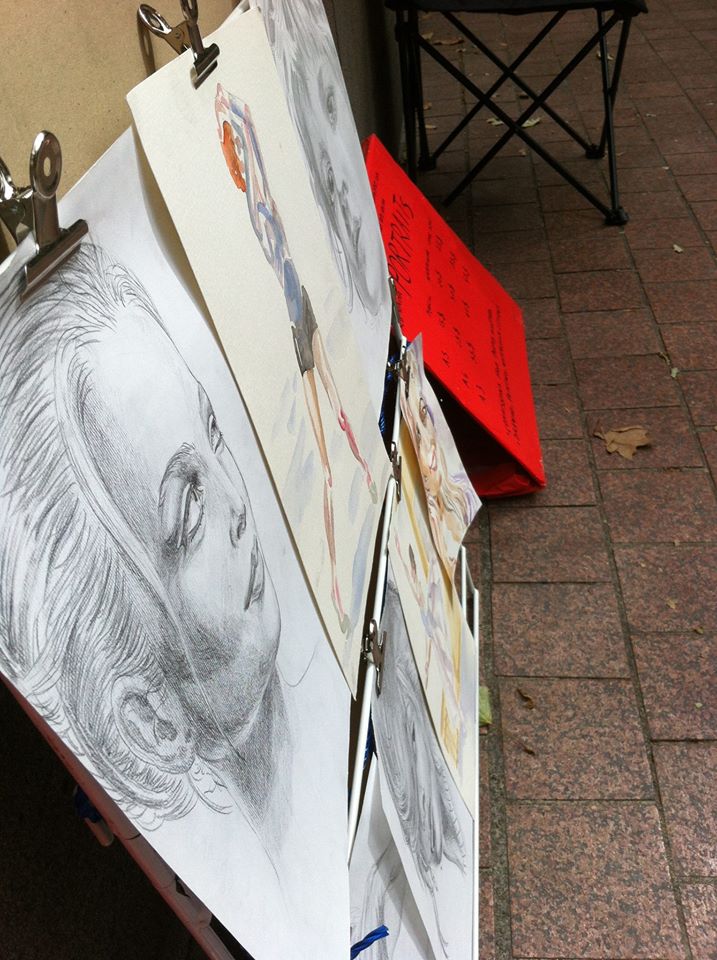

I finally applied for the license, prepared portrait samples and a sign with my prices. My supportive boyfriend even built a cart for my stuff out of a broken trolley we had found. That night I wrote excitedly in my diary: “This is the start of a new me. From today I will proudly be a busker!”

Making art on the street wasn’t an entirely new concept for me. In Positano, my hometown along the Amalfi Coast of Italy, I had a lot of friends who busked for a living – with successful results. In summer, the pastel-coloured Positano flooded with wealthy tourists happy to buy watercolours or have their portrait painted as a nice souvenir.

My busker friends – all in their fifties – were living bohemian lives. They had their aisles, their striped umbrellas and they were painting right in front of the beach. They’d exchange laughs with passersby and sunbathe while working.

One of them, Pasquale, taught me a lot about watercolours. He was ultra-tanned, had a small nose and a penchant for Asian girls, whom he attracted with his shabby Italian look. Even if I wasn’t selling my work, for three summers in a row I joined my busker friends and painted alongside them.

When the day was over, we sat on a bench carved in stone, watching the clouds turn pink and the sea purple. We chatted about everything, from Nietzsche’s Übermensch to that waiter trying it on. Being part of Positano’s busking community was paradise, so I figured that in Melbourne it wouldn’t be any different.

Looking for a relaxed environment, I steered away from the busy Swanston Street where Melbourne’s buskers usually gathered. I finally settled for a large curb on the way to the National Gallery of Victoria and set up my stuff there. As soon as I sat down on my fishing chair, I realised that the Melbourne experience was going to be dramatically different from Positano. The street was empty. And in the first thirty minutes, nothing happened.

I grew impatient and uncomfortable. Instead of painting to attract clients, showing that I cared, I decided to make clear that I didn’t give a damn about the whole business – you know, I just happened to be sitting next to these drawings. In fact, I started to text my best friend in Italy, complaining about how uneventful busking was. In hindsight that was quite meta. I was complaining about busking while busking – how postmodern is that?

Finally a hippie lady stopped. “Are you an artist? I can give you money, but not much because I’m an artist, too,” she said.

“Sure!” I replied. “Have a seat and I’ll paint your portrait.”

“Oh, sorry, I don’t have time for that – I’m in a rush. Here, have five dollars,” she offered.

I explained to her that I couldn’t take her money if she didn’t want her portrait done. She apologised, explained how much she related to me, then disappeared into the wide horizon.

I asked myself what part of “Have your PORTRAIT painted” plus pricing on my signboard was not clear. I texted my Italian friend who told me I should have taken the money – which showed that he, too, thought busking and begging were somehow related.

After two and a half hours, an old man approached me.

“Hello sir, would you like to have your portrait painted?” I asked.

“No,” he said. He just wanted to know when the free tourist bus was coming.

I told him that the next one was in thirty minutes, so he decided to sit and wait for it there with me. Since he didn’t seem to even consider getting a portrait, not even to kill time, I kept on texting my friend.

“You seem pretty laid back,” the old man observed. “You bet,” I answered.

Just after he left, a family took a photo of me without even asking. As she walked away, the little girl looked at my drawings and commented that she could have done a much better job. I resisted hitting her with my fishing chair. I’d had enough. I looked at the clock. Three hours exactly had passed. I left that spot never to return.

Walking home, I remembered what Pasquale had told me about what pushed him to show up to the same spot every day for thirty years: “I just love the freedom that busking gives you,” he said. “I like being connected with my surroundings while working.

“I can’t imagine myself trapped in a studio, having to make X paintings a year for a gallery. I tried that when I was younger, but it just didn’t feel right. It’s a gut feeling.”

As soon as I realized that, I felt suddenly relieved

What my gut was telling me was very different. The sense of being out of place I had experienced prevented me from giving busking another shot. I didn’t even consider trying another location; it was now clear I didn’t have the patience to wait for people to stop by. The idea of drawing at my desk, in the tranquility of my home, was suddenly very appealing.

As soon as I realized that, I felt suddenly relieved. You can’t say something is not for you until you try it. In my case, I had demystified my romantic ideas about busking and understood more about myself and my limits. You define yourself not only by the things that you do, but also by the things that you will never do, ever again.

Although my boyfriend was predictably pissed off that his cart would be left to rot, by the time I got home I had already thought of a new plan. I opened an account on Gumtree and offered myself as an art teacher – another short-lived experience that I eventually left for arts writing and journalism. But that’s a story for another day.

Image credits: Naima Morelli and Tim Mossholder