Jonathan Mok: Let’s start with personal questions. Marina Benjamin, in her book, The Last Days in Babylon, mentioned her rejection of her Iraqi-Jewish roots until she had a daughter. Unlike Marina, you were born in Israel, but grew up in the United Kingdom. What does being an Iraqi Jew mean to you? Have you tried to reject that part of your identity? Have you suffered from any discrimination when meeting British Jews of Ashkenazi background?

Rachel Shabi: Growing up in the UK, there was this assumption that if I’m Jewish I must be European-Jewish, so my culture was assumed to be one of Yiddish, Klezmer music, gefilte fish, etc. That was a bit weird – my parents spoke Arabic, played Middle Eastern music and wouldn’t dream of putting gefilte fish on the dinner table! But the majority of Diaspora Jewry is Ashkenazi so this cultural assumption about me is understandable. It’s a problem when you apply that template to Israel because it doesn’t work: half the population – and at one time a majority – is of Middle Eastern origin, or “Mizrahi”. This is easy to forget about Israel and forms the basis of my book.

Jonathan: Would you say that other British Jews of Iraqi or Arab descent share the observations you make in your book?

Rachel: I’ve been happy to see that the book does resonate for many other British Jews of Mizrahi stock. And some have said that they think what the book says is important – that it should be aired and discussed. Because, of course, the mainstream narrative in Israel is that discrimination against Mizrahis doesn’t exist – but from what I saw, it is still a very painful factor of Israeli society.

Jonathan: In your book, you illustrated the anger of Mizrahi Jews at the discrimination practiced by the Labor party, which is mainly ruled by Ashkenazi elites. You also mentioned that in the last two decades, emerging political parties such as Shas and Shinui were of racialized origins. How do you interpret the origins of Kadima? Should it be considered a party of Ashkenazi elites, even though some important members, including Meir Sheetrit and Dalia Itzik, were of Moroccan and Iraqi origins respectively?

Rachel: It’s not really a case of who is Mizrahi-origin and who is Ashkenazi-origin any more although it is true that in the first few decades, Mizrahis were almost entirely excluded from politics and government. Some people say that the political domain is proof of the fact that Israeli society is more ethnically inclusive these days. Conversely, you could say that the Mizrahi surnames in the Knesset prove only that you can be a Mizrahi politician as long as you don’t mention the Mizrahis, don’t campaign on that basis and don’t mention the specific and neglected needs of your community. Or if you do so, then you have to be a religious party – you have to be Shas.

When I travelled around Israel asking Mizrahis if ethnicity is still used against someone in the political sphere – as some have argued happened in the case of Moroccan-origin former defence minister Amir Peretz – people responded by saying of course it is and what planet was I living on. For them, it was a no-brainer.

Jonathan: Regarding the hawkish attitude among Mizrahi Jews over the peace negotiation with Palestinians, as you discussed in your book, how did such a right-wing position come to influence the Middle Eastern Jews whom you meet? Does the state help hatred of Palestinians flourish?

Rachel: A lot of Mizrahis I spoke to in Israel relate growing up in an environment that told them that everything that is “Arab” about them – their looks, accent, tastes, culture, outlook – was backward, wrong and presented an obstacle to their own social advancement. So it’s no surprise that Mizrahis then project all that “self-hate” onto their Arab neighbors. Also, hating the enemy is a way of proving allegiance to a nation that European Jews “pioneered,” [because the Ashenazis’] terrible suffering in the Holocaust gave the creation of Israel urgent legitimacy. So for Mizrahis, hating the enemy is one of the only options available to them as proof of national allegiance.

Jonathan: One of the most contradictory issues revealed in your book is the puzzling attitude of some of the Iraqi Jews you discussed in the last chapter of your book – “We are not Arabs”. How and why did the attitude “We like Arab culture, but hate Arab people” take root?

Rachel: Again, its the issues discussed above. I think the national narrative in Israel enforces this attitude – there is so much ambient racism against Arabs and Mizrahis simply conform to that discourse, although they at least are likely to respect the cultural output.

Jonathan: Finally, returning to Israel after two decades, would you say that the discrimination against Mizrahi Jews has been reduced? What would the solutions to this problem look like?

Rachel: It has reduced, definitely, but the underlying problem persists: namely, that half the population is Mizrahi but the culture is viewed as “low culture” or non-existent and this section of society is socio-economically weak and low status. And Israel, with a majority “Oriental” population, is still desperately trying to be a European outpost in the heart of the Middle East. I think that fundamentally needs to change before we’ll see any real improvements – either for Israel’s citizens or for the Palestinians beyond Israel’s internationally recognized borders.

I think improvements have to be based on affirmative action: if Mizrahis are half of the population, then half of the culture budgets should go to Mizrahi culture and half of all public service broadcasters should be Mizrahi and so on. Actually, the governor of the Bank of Israel said pretty much the same thing last year, with regard to the Israeli education system. He said the system had totally failed to level our socio-economic gaps in Israel and recommended affirmative action in the allocation of education resources. Socio-economic gaps are ethnic-based gaps in Israel.

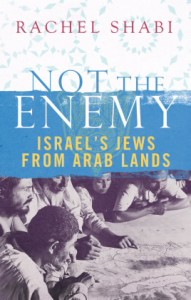

A review of Not the Enemy: Israel’s Jews from Arab Lands

Three years ago, while studying in Jerusalem, I was at the taxi station outside Ben Yehuda promenade, a group of taxi drivers surrounding me. I bargained for the lowest fare to go back to Mount Scopus, the campus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, but could not get a price that suited me.

I walked to the promenade from the Jerusalem Cinematheque in Hebron Road, wondering if a taxi driver in the Jewish side of the city charged less than an Arab colleague in East Jerusalem. I found a Jewish driver, but he had an “Arab look.”

On the way back to the university, I was curious about his origins. He, in his broken English, said “Morocco. Lots of Moroccan Jews are taxi drivers. The Russian ones only joined after the economic collapse.”

Puzzled by this dialogue with the Moroccan Jewish taxi driver, I raised the question of the status of Arab Jews one day when I met a think-tank fellow. He told me, “You heard of Shas before? It represents Moroccan Jews and most Arab Jews. The party is willing to “sell itself” to any parties as long as they give money to Shas’s social services. Shas will even support leaving the West Bank if it receives the money it wants! ”

I wondered then why Shas has to demand “special privilege” for its schools and social services, and about the larger issue of Arab Jews in Israel. And this year, a book has come along to provide us with a closer look at this segment of Israeli society.

In her debut, Rachel Shabi offers an unsettling illustration of the successive Ashkenazi-dominated governments’ discrimination against Arab Jews in education, culture, housing services and politics.

While the modern state of Israel was founded on Zionism- the ideological movement championing a safe heaven for Jews in the Holy Land – Shabi forcefully presents cases demonstrating the upper-middle class standard of living and harmonious coexistence with their Muslim neighbors that Arab Jews enjoyed in the Egypt, Yemen and Iraq. This safe heaven in the Arab world was actually torn apart by the creation of Israel. Worse yet, Shabi points out that the Zionists’ underground movement even bombed British, American and Jewish properties in Arab lands, misleading local leaders into scapegoating the Jews living there.

Shabi also buids a compelling case against the simplistic portrayal of Arab Jews as hawkish as per their involvement in the Shas party. Ignored by the Labor Party since the establishment of the state, Arab Jews were big supporters of the Likud Party in 1978. Likud, she says, betrayed the Arab Jews by investing the state’s resources into settlement projects to house religious Jews and Soviet immigrants. The formation of the Shas party, she argues, was therefore a natural occurrence.

The result of years of discrimination can be seen in the low socio-economical status of Arab Jewish families. Another consequence of the discrimination is the “identity crisis.” Too many European Jews do not accept Arab Jews as full members of the Jewish state, Shabi argues. At the same time, neither have Arab Israelis of Muslims background been too accepting of Israeli Arab Jews.

I found that the most depressing part of the book involved Shabi’s conversation with three Iraqi Jews in Kiryat Shmona. The ladies are speaking in Arabic and Shabi asks about their identity. One of them expresses her hatred of Arabs by describing them as killers. The loathing perfectly illustrates the fragmented state of the Arab Jewish identity.

The World Jewish Congress believes that “All Jews should be responsible for each other.” Shabi’s book suggests that there is still a long way to go before the statement will become reality. Sadly, when Shimon Peres and Ehud Olmert admitted the state’s neglect of its Arab citizens in years past, many then believed that the discrimination against Arab Jews was over. Shabi argues convincingly that this is not, in fact, the case and that Israel will furthermore never make peace with its Arab neighbors for as long as such attitudes persist internally.