The previous installment of the Stanley Kubrick (1928-1999) retrospective discusses “Paths of Glory.”

“While Fear and Desire [Kubrick’s debut] had been a serious effort, ineptly done, Killer’s Kiss…proved I think, to be a frivolous effort done with conceivably more expertise.”

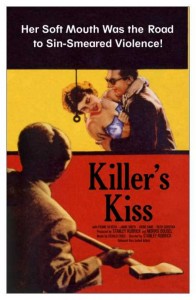

Kubrick’s own critique of his second feature reveals the director’s future marriage of lofty philosophical themes with nuts-and-bolts genre movies. “Killer’s Kiss” is a stepping-stone to grandeur, a youthful nod and wink to the peerless older genius that is waiting later through the stargate of “2001” and beyond.

Today we can shoot a film on our phones, edit it on our Macs and upload it to YouTube in a matter of hours. Back in 1955, the 27-year-old Kubrick was filming guerrilla style on the streets of New York with a $40, 000 budget loaned from his pharmacist uncle with no guarantee of distribution and financial return.

“Killer’s Kiss” is best seen as a moving photo story from Kubrick’s days as a photographer for Look magazine or an update on his short documentary “Day of the Fight.” His eye for the unusual transforms New York into a surrealist wonderland, a montage of hot dogs, fairy cakes and swimming dolls. He beats the French New Wave by some three years and breaks the 180-degree rule on the harsh Gotham sidewalks. His mirror shots point us in the direction of the “Shinning,” and arching shadows in an alley to “A Clockwork Orange.”

His dynamic hand-held coverage of Davey’s unfortunate title eliminator still takes some beating. The audience is propelled into the ring, participants in a black and white boxing video game, and are roundly smacked to kingdom come. When we rise we can almost taste the canvas and see little Martin Scorcese’s flying around our heads, filming his fight scenes for “Raging Bull.”

This is a real Theatre of Cruelty a visceral bombardment. We are denied seeing the baying crowd, but can hear their savage chants. Kubrick later repeats this with a dance solo performed by Iris to the voice-over of Gloria narrating the story of her father’s death and her sister Iris’ suicide. Once again, the audience is hidden in a deep black limbo, watching Iris who is seemingly unaware of her own violent demise.

In contrast to his later, symmetrical narrative structures, Kubrick experiments with flashbacks. In his next film, “The Killing,” he expands on this non-linear style and learns a crucial lesson – don’t rely on constant exposition in narration. In fact, “Killer’s Kiss” would be his last original story, everything else he filmed would be adapted, inadvertently revealing his cinematic Achilles heel.

His simple story of a boxer falling for a gangster’s moll, although hindered by the over-earnest score, is continually elevated by his expressionist locations. Davey runs for his life engulfed by hostile buildings that eliminate the sky and all sense of hope. The climatic fight amongst the Moloko Milk Bar mannequins has a haunting quality as well as a frenetic one. Hands drape down from the shadows, heads look on impassively, and bodies tumble as Davey finally drives a stake through the heart of his personal vampire, gangster Vincent Rapallo.

The young director was still an optimist at this point in his career, hence the happy ending, but “Killer’s Kiss” is an unpolished insight into the greatest of auteurs. This is a time before the mythical curtain of secrecy shrouded this cinematic Wizard of Oz. Davey’s career is described by a commentator as ‘one long on promise without fulfilment’. Stanley’s, at this point, was full of possibilities – one that would be fulfilled beyond the wildest expectations one might have for the director of “Killer’s Kiss.”

One thought on “On the 10th anniversary of Kubrick’s passing: “Killer’s Kiss””

Comments are closed.