Artist Rinus Van de Velde works and lives in Antwerp, and his last exhibition was in Seoul, at Korea’s International Art Fair.

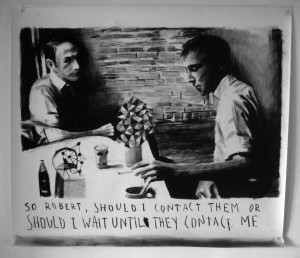

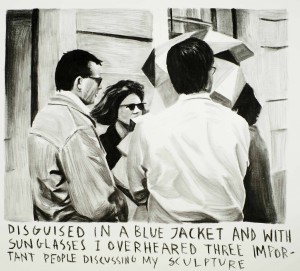

At first glance, Van de Velde’s works looked to me like old photos, taken from the archives of National Geographic and Life with seemingly random texts attached. The actual nature of his work, however, is far more interesting than that.

Jonathan: First of all, in your recent exhibition in Nuremberg, you highlighted your “relationship” with the Russian poet Valdimir Mayakovsky. Why have you been interested in what I call “virtual friendships” with the dead, rather making “ real friendships” with the living? Why did you choose Mayakovsky?

Rinus: I have never really thought about the distinction between virtual and real friendships. Even if I would have come up with a story about me becoming friends with someone who is real and/or still alive, it would still be a fictitious story — my work is studio based, and is not a reflection of my everyday life. I treat Mayakovsky as a character that is made up, that is in fact representatives or personifications of me.

In my texts, I choose a first person narrative, and by this I spell out and appropriate the elusive subjectivity of the other. For me, this appropriation aspect is very important: by weaving my fictitious story into the ‘real’ biography of Vladimir Mayakovsky, I try to make his story my own, and create what one could call a mythical biography of me.

I believe this self-conscious untruthfulness is a necessary strategy in dealing with identity and the self: ‘The final believe is to believe in a fiction, which you know to be a fiction’, as Wallace Stevens wrote.

Of course, I’m not just looking to design an absolute fantasy in which everything is possible; I want to create a story that could have happened that you can believe in, although at the same time you know it never took place.

I could write myself into Mayakovsky’s story, and make the relationship between self (the I-figure) and alter ego (Mayakovsky) more complex.

Another thing I find interesting about working with a historical character is the anachronistic aspect: by imagining that I was part of a different historical period, I can investigate the contemporary traces of issues that are supposed to belong to the past. At the same time, it becomes possible to make tangible how the past is always penetrated by a present point of view. For example, I found Mayakovsky very interesting and attractive because he was an avant-garde poet with a quite big impact on society. I think today this heroical status is completely unthinkable for an artist.

Also, Mayakovsky’s link with the visual arts is not so obvious. This made me able to focus more on biographical elements, like his obsessive character, his triangular relationship with Lili and Osip Brik, his fear of dirt, his gambling addiction… I think the fact that his life lends itself so well for story telling that interested me in the first place.

Jonathan: It seems to me that most of your works have been printed in black and white, except the sculptures you have displayed in Nuremberg. Why is that the case?

Rinus: All the drawings I made in the last 3 years are indeed in black and white. For me, drawing traditionally occupies a marginal postition in the history of plastic art. I am interested in this medium of drawing exactly because of its fast, experimental nature. Drawing is a means of finding your way about things, that is quicker than mediums like sculpture. I agree with Walter Benjamin’s view on the symbolic nature of the ‘flat’ drawing, stating that it ‘is not a window on the world’, like a painting, ‘but a device for understanding our place within the universe.’

So, to be able to focus more on the fundamentals of drawing, I started using use charcoal.

By only using black and white, I can link all images to each other. Every image can hang next to another. For me, my work doesn’t exist in single pieces, but forms an archive that tells a story on the wall. Apart from that, I also like the documentary feel of black and white. It refers to a time that is past, and thus suggests memory.

Another reason why I switched to charcoal is because I found the colours were in a way an obstacle. You have to think if the green goes with the red, or what happens when you put one colour next to another. It slows down the process, and it has always been important to me to be able to work fast, so that I can come to a multitude of drawings.

I try to tell a story on three different levels. There’s the very concrete level of the sculpures, the more representative level of the drawings, and the symbolic level of the text. All three levels should functions autonomously, but in the best case work together in a installation. The fact that they work together as a part of one work, doesn’t mean that they confirm each other. The different elements in an installation will interact when they clash.

Jonathan: 27 is young for an artist. What do you think about the impact of market and different tastes among clients and investors on your creations when market value is increasingly becoming the criteria to determine the success or failure of an artist?

Rinus: I don’t believe in the idea that the artist is completely independent when he or she is creating a work of art, as if his or her personality is superfluous. I think making art, or an oeuvre, is entangled with creating your own, personal story, and for an artist today this story also invloves taking a place on the art market.

However, I strongly believe that galleries today are more than ever before influential. For all artists, it is important to map out a strategy about where to show their work, which gallery you work with, which collections your work should end up etc. On the other hand, I believe that a good gallery takes care of these practical, strategic questions, together with the artist, and that this might even help to come closer to the utopian model of the independent artist working solely in the studio and taking care of the quality of his work.

But in the end the question of market value comes down to the impossible question of the subjectivity of ‘quality’. For now, I tend to believe that a good artist is able to pronounce a strong personal definition of what art is.

Jonathan: Finally, what is your plan for next art series? Or any plans to go into “ new world” like the States. I ask this since except two shows in Miami and Hawaii, you have mainly exhibited in Belgium and Germany.

Rinus: I am always working on new drawings, since I consider my work to be a continiously enfolding story that crosses the boundaries of distinct series. As for my future plans, I like the approach of the Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers in La conquête de l’espace.

(Interviewer’s note: Marcel Broodthaers was born in 1924 and passed away in 1976. Broodthaers is a Belgian poet, filmmaker and artist known for embedding 50 unsold copies of Pense-Bête in plaster to create his first work. The Tate Gallery in London and Museum of Modern Art in New York own his works.)