Since its big screen debut, Sorry to Bother You has had a lot of labels thrown at it. Revolutionary. Science fiction. Dystopian. I’ve even seen horror lobbed around a couple of times. And of course, there are the inevitable comparisons to indie hit Get Out in terms of style and subject matter.

To get a few of those out of the way: yes, Sorry to Bother You speaks directly to racial relations in America. Like Get Out, it explicitly centers the black man’s experience as something universally relatable for black folks, although Sorry to Bother You at least somewhat explores the reality of being black and female. And yes, some weird freakiness goes down in both movies as an exaggerated metaphor for the predicament of navigating life as black – in Get Out it was literally white folks hijacking black bodies, here it is white businesses turning marginalized workers into workhorses… literally. A lot of similarities to be made here, but Sorry to Bother You opens up a whole different conversation with its critical plot point of the “white voice”.

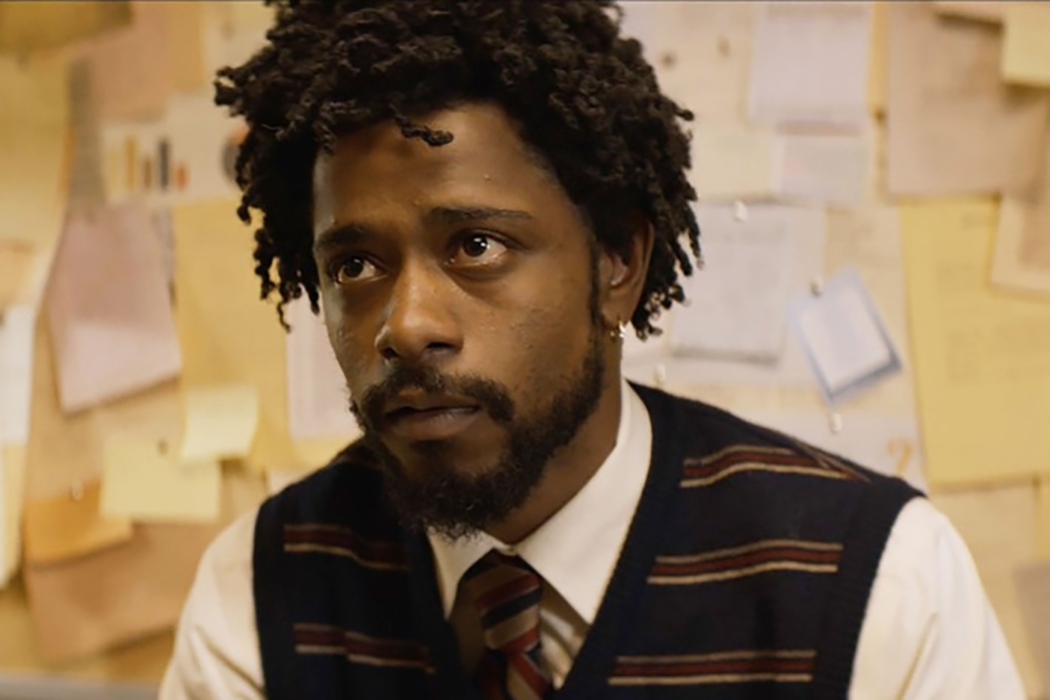

Cassius (“Cash”) Green, a struggling young black man from Oakland living with his activist artist girlfriend Detroit in his uncle’s garage, has just obtained a new job as a telemarketer. It isn’t until an older coworker encourages him to turn on his “white voice” that he begins racking up sales and becomes a power caller. Cassius soon finds out that his newly awarded privilege puts him in a precarious position and it doesn’t take long for him to discover the dark secrets of selling your soul for corporate.

The world of telemarketing and customer service is already difficult for marginalized folks, especially if you dare possess an accent. As the movie is based in the US, this would be anything less than a voice of newscaster perfection. Code-switching becomes a tool for survival, especially regarding phone customer service where anyone could be at the other end of the line. Naturally timid and withdrawn, Cassius isn’t doing well at gaining his customers’ attentions. According to his friends and family, Cassius sounds white – that is to say, removed from stereotypical black qualities. But as older coworker Langston points out, he doesn’t sound like the type of white that commands attention. The voice that white people that embodies white people’s’ desires and wishes, and what society sees them as.

Cassius’s dilemma answers an age old question for activist groups: who do our allies listen to? Specifically, when it comes to issues of marginalized folks, who do the dominant class listen to? The most obvious answer is “themselves”. Allies are often told the best thing to do is to talk to their peers and boost the voices of marginalized groups. Only then will they listen, right?

It probably shouldn’t surprise anyone, but turns out the dominant class doesn’t exactly listen to its own. The most recent example would be Anne Hathaway using her platform as a celebrity and as a white woman to call for justice for Nia Wilson, a young black woman killed by a suspected white supremacist. Anne accurately discusses the intersections of race, gender, and violence, but the most scrutiny has come from other white folks. If you think that being a woman has something to do with distorting her message, there are male examples as well. And it’s never been more clear that white folks aren’t listening to people of color either. Who do they listen to? Science? God?

As Sorry to Bother You explores, white people listen to their own projected images. Confidence, power, money. White folks listen to whoever sounds like what the media portrays them as. When Cassius effortlessly slips in and out of his David Cross-fueled white voice, it’s almost like soothsaying. It’s implied in the movie that this voice is innate within people of color: Cassius’s friend Salvador channels his own, so does his girlfriend Detroit to boost the profile of her art. The only person that doesn’t channel such a voice is Squeeze, who is Asian American and that probably kicks off a whole different discussion in itself.

But as the events of the movie unfold, we see that the ability to channel a “white voice” puts one in a precarious work situation. Cassius is later viewed as a traitor to his coworkers when he breaks the Regalview telemarketer strike after obtaining power caller status. Detroit prides herself on guerrilla activism, but channels her posh, Lily James voice to sell her art which is only found in the residences of upper class white people. Because of their liminal positions, Cassius and Detroit are used as battering rams and bargaining chips to their respective communities. And when Cassius comes to his senses and subjects himself to humiliation to warn the world about billionaire entrepreneur Steve Lift’s nefarious plans with Worry-Free (a satire of the for-profit prison system), his choice to communicate to those who would be able to do anything as himself, a black man, backfires.

Sorry to Bother You encapsulates the struggles of black life in the US. It asks who do any of us listen to and who do we answer to. It laces together the intersections of race, privilege, gentrification, and employment and delivers a subtle but strong message to its black audience – no surprise given that it’s the brainchild of Boots Riley, noted hip hop musician (The Coup) and Communist. It’s not a movie for everyone but its message deserves to be heard, directly.