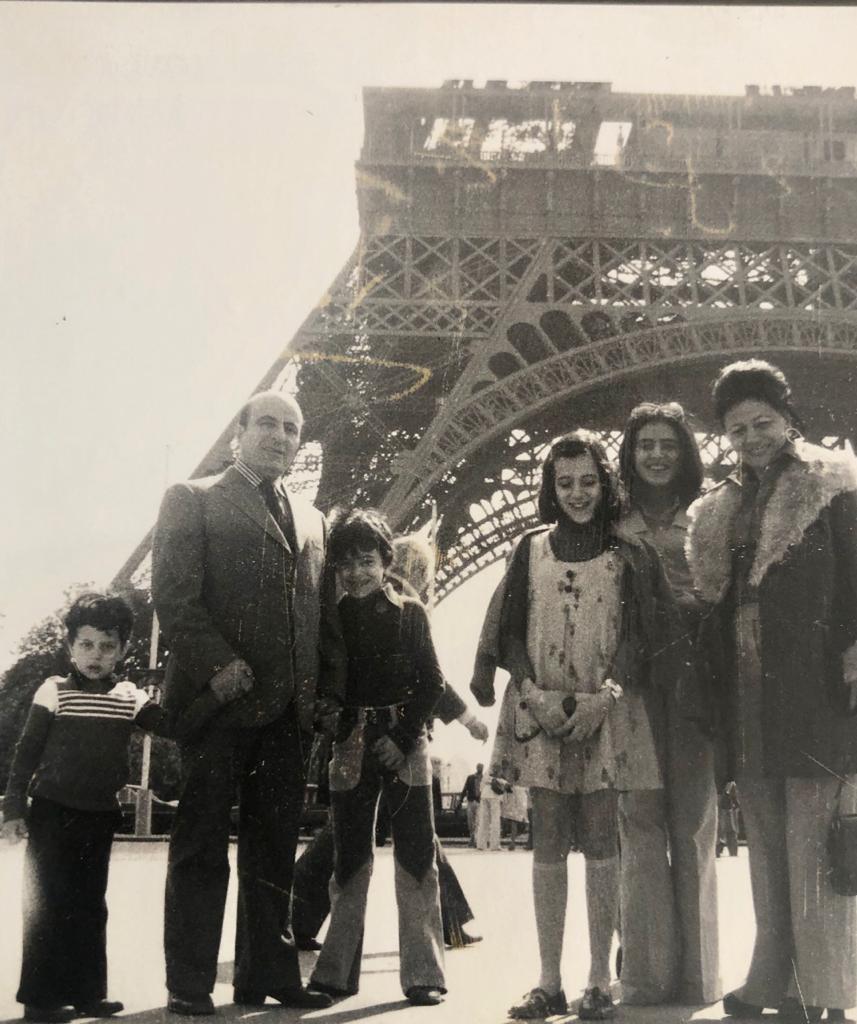

Every year, on my birthday, I would get a call from my father. Invariably, he would tell me something along these lines: “The day you were born was a bank holiday Monday. It was a wonderful summer day. The sky was the bluest sky I had ever seen in all my time in London.” In the early years, when I of course feared death but still saw it as a distant reality, I would laugh an embarrassed laugh, knowing my Dad must be exaggerating a little bit. In the last few years, as Parkinson’s disease and old age battered my father, those familiar few lines would always cause a slight gush as I fought back a tear or two and the unstoppable lump in my throat. My birthday in 2017 was the only one of my life until then on which I didn’t hear those familiar words. The only call that day was from my sister. I thought she was calling to wish me a happy birthday, with my dad by her side. Instead, she told me my father’s health had taken a major turn to the worse and that I should travel back to Jordan.

My father passed away in Amman on the morning of June 3, 2017. The love of his life, Kaidy, had passed away also on a June morning two years earlier. The choice of hour and month must surely be the work of fate, or whatever magic binds the major events of our lives and gives a certain air of logic to it all.

My father died gracefully and peacefully. I choose these words carefully. Before I get to my father’s achievements in work and family, I want to call out that extraordinary dignity and character of his. It was always there. But what I truly marvel at is how those characteristics shone brightest in sickness and old age. No matter how much the years and bad health took of his energy and drive, there was always an air of serenity and quiet dignity that charmed all around him. The nurses that took care of him, and the many friends who would get to know him only in old age, all were struck by that patient, calm, and caring demeanor. One of my best memories is of the banter between my dad and my friend Omar during my father’s visits to Dubai in the last two years of his life. Omar vaguely remembered the days when my Dad was the lion of the Potash Company in Jordan, but it was the man of 89 years that Omar would get to know and appreciate over casual dinners at home. Omar will now tell anyone who wants to listen how exceptional my father was.

This all taught me a very important lesson. It is not in tangible achievements, titles or prestige that the essence of a man lies. It lies in the core of his character, principles and the way he handles himself every moment of any given day, no matter how the wind is howling around him. My father’s beautiful core was always there, whether it was in his youthful energy in the practice of politics in the 1950s or in his late 80s having dinner with friends and his beloved granddaughters Oceane and Souraya.

Early Life

My father was the proud son of Nu’aymeh, a village close to Irbid in North Jordan. My father was always proud of his village and of the Khasawneh family; it was always a pride steeped in the achievements of the good people of our wider family, but never, ever, tribal. Some Khasawnehs still chide him for never giving way to the pressures of wasta (the infamous Arabic word for nepotism) and appointing relatives in the companies that he led. My father adamantly refused to appoint or promote anyone except on merit.

The story of my dad’s youth runs through the challenges and limitations of British colonial rule in Jordan. One might assume that the ‘enlightened’ occupying administration would have focused on education and building schools. Instead the reality was the absolute opposite. There wasn’t a single secondary school in the whole north of Jordan! Only the top students would be allowed the privilege of continuing their education in a secondary school in Amman or Salt. And so it was that my father essentially had to leave his family home to study in Amman… at the age of 9! He lodged with a family and attended school in Amman, and then finished school at the legendary secondary school in Salt, a city near the capital.

That determination saw my dad achieve an education that surpassed that of many of his friends and counterparts. He studied Economics at the American University of Beirut, a bastion of enlightenment to this day, and then did a master’s degree at the George Washington University in the United States. Through it all, he persevered against the odds.

Political Activism

My father’s career started in government. He served in the Jordanian Ministry of Economy in the 1950s. But that service, in memory and the way he recounted it, seemed like a minor backdrop to his active career in the revolutionary politics that flooded the Arab world at that time. My father was a young yet leading figure in the Ba’ath party, a progressive Pan-Arab party at the time. He started his Ba’ath tenure while studying in Beirut. He was fortunate in how quickly he rose through the ranks and got close to its leadership. My father got to know the legendary founder of the Ba’ath party, Michel Aflaq, during his stay in Beirut. He would always tell us stories of how Aflaq was a very careful thinker. My dad would at times stay by Aflaq’s side as he dictated his latest article. He would tell us of the long pauses Aflaq would take as he carefully plucked every word from the deep thoughts swirling around his mind.

My father would play a key role in recruitment to the cause, especially amongst the young in Amman and across the country. I was always mesmerized by his descriptions of these tumultuous and dreamy times. There was an energy and integrity to the practice of politics, and the young were mobilized in active pursuit of their ideals. Unlike any moment before or since, progressive and democratic principles held sway on the Arab street. I loved nothing more than hearing my dad tell us how in the 50s, the Ba’ath and other progressive parties controlled most demonstrations. He would tell me that Islamist parties would struggle for attention, and would always occupy a negligible corner in any patriotic protest that took place. They were a minor detail. How the times have changed!

My father lived that moment of possibility to the full – until he was jailed! The Jordanian authorities cracked down on Ba’ath and other progressive activists. Without being charged, my father spent around a year in total in incarceration. A small part of that would be in a normal jail in Amman, but the bulk of it was in a massive detention camp in the Jafer desert, in the south of Jordan.

I have always found it difficult to characterize my father’s time in detention and how he felt about it. On the one hand, he saw it as part of the narrative of the modern Arab world, of so many authoritarian governments in the 50s and 60s that destroyed any movement that would liberalize the masses and edge us closer to true democracy. But on the other hand, there was a fondness to the way in which he recalled those times. I presume he looked back nostalgically at an era in which Arab youth were by and large enlightened and shared a vision of a greater and unified Arab world. He had wonderful memories of his time in Jafer. Deep bonds were formed under the starry skies of the Jordan desert. One of those bonds was with my dear uncle and Kaidy’s brother, the legendary Arab jurist Hamdi Abdul Majeed, who then went on to achieve great success as a lawyer and head of the lawyers Union in Jordan and as the Chief Legal Advisor to the Dubai Government for almost 40 years. They would both tell us stories of the prison guards and their kindness, of talking through the night and making big plans for the future, of my father’s cooking (a pastime he enjoyed his entire life) and a lot more.

While my father didn’t have an ounce of bitterness about detention, he was always more slighted by what happened next. He was exiled and not allowed back in the country for over 10 years. His exile was only overturned in the late 60s by a fellow patriot and the greatest man ever to hold the position of Prime Minister in Jordan, Wasfi El Tal. For the non-Jordanians reading this, they may doubt this sudden moment of rhetorical flourish in describing El Tal. However, almost every Jordanian reading this will be nodding their head with approval. Of the scores of Prime Ministers that have served the country since the country’s inception in the 1920s, one name always tops the list of the handful of PMs that have served with vigor, patriotism, courage and pride. And that name is Wasfi’s.

A small note needs to be made before concluding this section on my father’s political career. My father belonged to a small group of Ba’ath activists that resigned from the party the day it resorted to coup d’états to gain power. He never looked back. For progressives like my father and uncle, the party was completely finished the day it resorted to violence and military force. My father would often tell me: “A political movement that needs a gun to get to power is no movement at all.”

Kuwait Oil Tankers

With his political career behind him, and Jordan no longer an option, my father turned his focus to a business career. Reluctant to leave his ideals behind, he chose to focus his non-political life on working on great Arab economic projects. He started as the manager of the Arab Bank in Khartoum, Sudan. The Arab Bank is arguably the most successful financial institution to come out of the Arab world. My father got to know the founding Shuman family well, and he always spoke in glowing terms about Abdul Hamid Shuman, who helped to take the bank to great success from humble beginnings in Palestine. It was the founders’ drive to build a genuinely successful Arab enterprise that appealed to my father most.

In 1961, my father had one of the key turning points of his career. And he always credited it to a good friend of his, legendary Jordanian businessman Kamal Al Sha’er (founder of the multinational engineering giant Dar Al Handassa). On a random day in Khartoum in 1961, my dad got a call from Kamal. He told him that he was speaking to a board member at the Kuwait Oil Tanker Company (KOC), one of the biggest tanker companies in the region, and that they were looking for a new CEO. Without a moment’s thought, my father said he’s interested. A few days later, he took what was then a long set of flights to get from Khartoom to get to Kuwait City. He spent only half a day there, met the board, left, and got offered the job a few days later.

He took on the work at the helm of KOC as a man on a mission. He was always highly driven, but the opportunity to devote himself to a project for the benefit of the Arab economy and future generations gave him the impetus he needed to soar. For the next 23 years, through this experience and the Potash company in Jordan, he never really had a day’s rest. He was fulfilling his life’s work.

In Kuwait, he devoted himself to building a state-of-the-art fleet of ships, owned by Kuwait and for the benefit of Kuwait. He was determined to train the workforce of the company and ensure they gained the necessary expertise to run the fleet of tankers carrying petroleum products around the world. One of the key elements of his KOC experience was the friendships he developed at the board level. The board was filled with leading characters of Kuwait’s old families like Baher and Saqr. My father would tell us for years later of the unique tenaciousness of these men. They supported him in the interest of the company completely and without regard for consequence. They were of that brave breed of Arab men, rooted equally in history and that rare sense of patriotic duty, who at times seem sadly to belong to another age.

In 1968, for various reasons, the board of KOC decided to move the headquarters of the company to Europe, and gave my father the choice of city. He chose London (hence that sunny London day on which I was born). My father continued to serve for another 7 years at KOC. He developed a fleet that continues to thrive to this day, and is one of the very largest in the Arab world.

Every time I see the name of the company in the news today, I can hear the voice of my father and the proud way in which he pronounced the name of the company in Arabic: Naqelat Al Naft Al Kuwaitiyeh. With emphasis on every syllable. A few words that for me and my siblings speak of duty, success, and the boundless promise of our region when spurred on by the passion of good men and women.

Arab Potash Company

In 1975, my father got another call. This time from the Jordanian Government. He was asked to head the Arab Potash Company. The aim of the company is to harvest and sell the multitude of minerals of the Dead Sea. By the time my father arrived at the office, the company had been in existence for over 20 years. And literally almost nothing had been done. One of my earliest memories in life is going to the site of the company at the time and noticing the vast emptiness of achievement!

It is fair to say that this was the seminal moment of my father’s career. He worked night and day to turn the company around. He would divide every day between time in the office in Amman and the site of the company by the Dead Sea. This involved traveling the old mountainous road from Amman to the site. I simply cannot exaggerate the dangers of that road at the time. I remember it well, as the car would navigate narrow roads shouldered by the deep unfenced void of the valleys beneath. One small turn, one tiny loss of concentration by the driver, and the car would fly down into immediate extinction. These daily drives of my father marked my childhood. Every evening, my mother, whose love for my father and fear of death of loved ones were equally astronomical, would wait at the porch of our house in Shmeisani. With no mobile phones or any mode of contact at the time, the vigil would start at the hour it was expected my father would return. Unlike me, my father was famous for punctuality. But the traffic on those treacherous drives was completely outside his control. As the return got delayed, my mother would pace Jaheth Street up and down in deep concern. That daily fear of something happening to my father in this call of duty marked me for the rest of my parents’ lives. When we realized that my father had passed on that June day four decades later, one of the first images in my head and heart were of that wait outside our place. The day has come when Baba didn’t return home.

My father spent 9 years at the helm of the Potash Company. In that time, he led a mammoth effort to generate more funding for the company from the World Bank and various Arab Governments. He was so fond of his team of engineers, managers and every employee of the company. Together, they turned around the company and led it to full production by 1983. As is the case with every such effort in Jordan, the resistance from some elements of the entrenched establishment was immense. But my father found in the end a great deal of support from the various Prime Ministers that served Jordan at the time. My father was particularly grateful for the extraordinary support he got, and against the odds so often, from Mudar Badran, another Jordanian PM who was a portrait in courage. Badran had a natural understanding of the importance of what my father and the Potash team were doing and was ready to support them over the unnecessary red tape and obstacles thrown in their way.

Caption: With King Hussein, Crown Prince Hassan and Prince Michael of Kent during a visit to the Potash project

The pictures above were taken the day of the official launch of production of the Potash Company. It is fair to say that it was the proudest moment of my father’s career. He had led a home-based Arab economic project to success, and made the exports of this company, to this day, the second largest out of Jordan. It was a day that it all came together. One thing worth noting is the genuine bond of affection that grew between my dad and King Hussein and his brother, the then Crown Prince Hassan. My father got complete support from them both at all times. On one occasion in 1982, when some of those shadowy figures that sadly still hover in the corridors of power in Jordan, managed to manipulate matters for my father to resign, we were all sitting in the living room and the phone rang. My sister Lulu called out “Baba, someone’s on the phone and he says the King is with him!” The King spoke to my dad and convinced him to return to his position. Prince Hassan was involved in the day-to-day running of the economy, and the interactions were constant with my dad. My dad had endless stories of the Prince’s surprise visits and his love of checking on things personally, and field work in general.

It was quite a journey from Jafer prison to the opening of arguably Jordan’s most successful economic state-owned enterprise.

My father was always very clear that the Potash Project would not proceed successfully unless it was run with efficient management and without much interference from government bureaucracy. I mentioned above the shadowy figures. I’m afraid this will resonate with many Jordanians. Throughout our recent history, we have had to contend with so many people, entrenched in the various arms of the government, that see governance essentially as a matter of collective self-interest. These are groups that form within the organs of state and compete with one thing in mind: power and the self-fulfilling privileges that come with it. Sadly, success in government on many occasions has been linked with the ability to navigate these various groups. My father refused to play that game from the moment he landed in Jordan. This of course won him a large number of enemies.

Those shadowy figures worked tirelessly to undermine him and, in 1984, found a technical loophole to force my father’s hand. He had to decide whether he would carry on in the role in the way he thought it best or with one hand tied behind his back. He chose to resign. For the rest of his life, my father never once second guessed his decision to leave on principle. For the rest of his life, he would also regret the fact that circumstances did not allow him to continue growing the Potash Company in the multitude of directions he wanted. He details all of this in the beautiful autobiography he published in the early 2000s titled “Strangers in their Own Homeland.”

Family and more

After the Potash company, my father worked in a private investment company, based in Switzerland and owned by Syrian Kuwaiti businessman Khalied Osseimi for about 10 years before retiring for the last 20 years of his life. The work in private business allowed my father to make much-needed money to finish our education and be able to retire well. He was always thankful to Mr. Osseimi, and developed a lifelong friendship with him. But it is fair to say that he never felt at home anywhere other than when working on major projects of importance to Arab countries. Professionally, that was his life’s calling. We pleaded with him in his retirement years to start his own business. He resisted until the end. I am sure he would have achieved tremendous things in that domain too. But for him, work was essentially an act of faith. He had to have a mission and believe wholeheartedly in what he was doing. Otherwise, he was content to stay home.

As I honor the memory of my father in this article, it was very important to highlight his achievements in business and politics. His work deserves recognition. But as his son, the legacy of my father is all at home. His work success only matters in the sense that I have always found myself lucky to have had a father I can genuinely look up to. And I always did. With the passing of the years, and as we assess the world around us more critically, I have always challenged myself on that. Was I guilty of over-glorifying Baba? All I can say is that after a great deal of self-assessment, I still arrive at the same place: he was an extraordinary man by every measure.

As a father, the first thing that surprises me to this day is that I do not have a single recollection of him ever losing his temper at me or any of us. Not once. This wasn’t only about the nature of the man, it was about his deeply held view of what parenting is all about. He had an unchanging belief that fathers and mothers must always be the bigger people. He saw any loss of temper by a parent as a reflection on the parent and not the child. He believed in discipline, but only of the kind that comes through communication. When he scolded you, he did it in a way that is far more effective than a million screams. He did it calmly, talking to my mind. My dad disciplined me by humbling me. If he could handle situations with such grace, what right could I have to be a pain?! He’s genuinely the only parent I have come across who managed the entire process without ever allowing his own ego to come into play.

He also made clear that our decisions were our own. If one of us was about to make a massive mistake, he would never order or demand a change of track. I’m afraid he dealt with quite a few of those moments with me and possibly one or two of my siblings! One major incident in this regard was transformative for me. My father took tremendous pride in our achievements. I hope this doesn’t come across as conceited, but he was over the moon when I made it to Oxford University. He literally told everyone about it, including passersby in the street possibly. But in my first term at Oxford, I felt rather miserable and was a bit overwhelmed by it all. I started nagging endlessly about it, mostly to my mother initially. But one day, on the weekend in London, I nagged about it to my dad, and how I would rather leave Oxford. I felt really bad because I was sure this would break his heart. I was expecting an argument, or at least sadness. He simply and gently said that I should leave if I’m that unhappy. He then went into another room. He came back a while later and said that he sent faxes to a couple of other universities to see if I could join the following year. I was dumbfounded by that. It shocked me to the core. From that moment on, I never spoke again about leaving and I finished my three years at Oxford. I still think that if that day, my father allowed this to become a major argument or any form of verbal duel, I would not have stayed the course.

My father cared for us ferociously. I always felt looked out for. The image that stays with me always is of my father on car drives. One of my mother’s favorite passions was taking a long drive with her and my dad’s favorite songs on playback (a habit that must be genetic as it has passed on to my daughters Oceane and Souraya, who love nothing more than a long drive with music blasting at the loudest decibels). The same songs played in my parents’ car drives from the 70s till the end of their lives. Fareed Al Atrash, Najat al Saghira (especially the song “Ayathun”) and, of course, Um Kulthoum. I remember my dad driving us on Fridays in Amman, across the blossoming Jordanian spring countryside that lined the roads to Jerash, Salt, and various other towns. He would take us to visit relatives in Nu’aymeh, and would drive us in England across various stages of life.

My friend Firas often recounts the day he visited us from France in the late 80s. There is nothing specific to the memory. Firas just recalls my dad and I waiting for him at the airport, and how impeccably dressed my dad was (I presume I wasn’t!). He talks of how gracious and noble he was and how Firas was made to feel like a visiting lord. Firas also remembers how my father cooked for us. Another close friend, Subarna, also always recounts how touched he was by the fact that my father made us lunch a few times in London. My dad loved cooking but his range was small. When he treated us to his culinary skills, it was essentially either Galayet Bandoura (an Arabic tomato dish), leg of lamb or fried eggs. It was extremely good and, in all cases, yet another area where my father was infinitely more gifted than I am.

A lasting memory is my father’s hawkish look at the road whenever he was in the passenger seat and someone else was driving. He was so worried about accidents when we were with him in the car. So much so that I have never seen him take a nap in a car. He keeps looking at the road, presumably with the thought that his co-captain skills can save the day if necessary. I used to plead with him when he got older to relax and sleep. But he never did. He was always watching the road for us.

My father and mother had a method to upbringing based on positivity and responsibility. Their focus was to always make each and everyone of us feel special. Not special in the spoiled silly sense. Not at all. But special in the sense that they were confident that we have it in us to achieve our potential. To this day, I believe it is the best method to parenting and I try to apply it with my daughters. It is a nuanced approach. Once again, that thing of leaving ego and your own emotions behind lies at the heart of the success of this approach, and it’s not easy at all.

The anchor to all of this was something simple yet so difficult to attain: Two people who loved each other for life. My father’s love for his wife of almost 60 years, Khadijah Abdel Majeed, is truly, for me and many others, the stuff of legend. He loved her in every way under the sun, starting from the day they met and that unique name he gave her: Kaidy. Our lives were centred on one thing: at the end of any day in Amman or London, we were assured to come back home and Ali and Kaidy would be sitting in the living room chatting endlessly, watching TV and engaging us all in their banter. Their extraordinary bond was on display every single night, whether having Baba’s unique blue cheese sauce for chicory or chips and watching Newsnight in London, or the fiery conversations they would have while Um Kalthoum (or Sky News) played in the background in Amman.

They looked up to each other. Each of them believed to the core of their being that the other one is remarkable. Kaidy, to her last breath, believed that no one matched my father in integrity, patriotism, and character. My father believed, to his last breath, that no one was more beautiful, more intelligent, more elegant and more passionate than his Kaidy. That was the most extraordinary thing about their marriage. And it’s not like they were the dreamiest romantics on earth; they were both highly practical people, yet they believed in the extraordinary in each other.

That bond between Kaidy and Ali underpinned our lives. As we get older and look back on their marriage, it just all becomes the more exceptional. Having had my own share of struggles in that department, I can only marvel at that magical gold dust that held them so tightly together.

When I look back at my father’s life, I cannot but feel blessed; I literally cannot imagine life without his example serving as a constant guide and torch light helping me through life and its challenges.

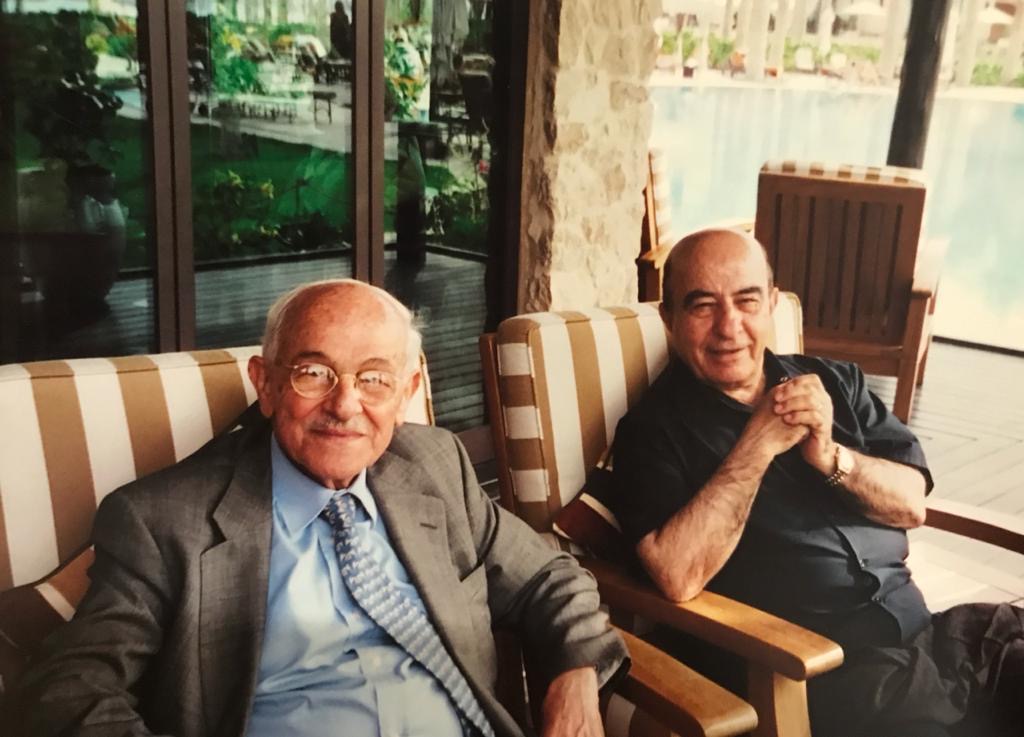

One of the things I am most proud of is that I managed to have my father travel and visit me in Dubai twice in the last two years of his life. He was frail but he seemed genuinely happy to be here. He always marvelled at what Dubai has managed to achieve. His dear and lifelong friend Hamdi Abdel Majeed was sadly in the ICU unit of Al Rashid hospital during both visits. We would still go and visit Khalo Hamdi in hospital. Two old comrades united in the very last chapter of their extraordinary lives.

On the last day of my father’s last visit to Dubai, we went to Muchachas (a recommendation of a dear friend), a nice Mexican restaurant in a hotel near the then newly-built Dubai Water Canal. I had a strong feeling this would be the last day I spent in full with my father.

After lunch, we went to walk by the side of the water canal. The February sky over Dubai had its usual share of scattered clouds. My father sat with a smile as we rolled his wheelchair. My father suddenly burst into song as he often did over the years. He would sing, with a youthful grin, songs of Jordanian villagers that he had learnt as a child in Nu’aymeh. On that day, he sang the classic “3ala Dal3owna” folk song. Though my father never really knew a moment of true happiness since the passing of our mother, I dared to believe that, for that one fleeting moment, he was genuinely happy. I also dared to hope that, in the overall balance of things, I have managed to be a good son to this most extraordinary man and father.

WOW. Nasser, you managed to do what only few can do : you translated deeply personal feelings into words, with a precision that is unmatchable and worthy of some major acknowledgement! I’m speechless, cousin! A truly special and heart-warming (at times wrenching due to its poignancy) tribute – from one great son to one great father and legendary man. Felt your every word Nasser. Felt your huge pride, your love, your loyalty, and your burning need to honour your father’s legacy. I read the first few paragraphs and kept wanting to read on – not only because you are an amazing writer / storyteller and had me completely captivated from start to finish (offering us a gripping account of past events about ‘real’ and courageous men)- but because you wrote from you heart about a man who is obviously like no other to you and is simply unrepeatable (I know firsthand how hard that is and at times dark and draining) and because you literally brought Ammo Ali back to us through your clever writing. You truly did – with utter brilliance and humility, and with a Nasser-like humour which I know so well, and if I may admit openly cousin – love so much. You brought our Kaidy back to us too, and my dear father – which moved me immensely. I miss them all so much. You’ve captured everything and brought your father’s character to life – what prompted his decisions, what he stood for, his devotion to Kaidy and his family, his love for his country, his loyalty to his friends, his successes, his hard work and passion towards his work, and ultimately his life purpose – all there, and all woven into a beautiful web of a life lived well, and honourably. Rest-assured you have done your father justice, and he would be so very proud of you. He is. Like father like son, undoubtedly.

This is such a remarkable expression of love and respect to your father, Nasser, that only very few could ever do. I felt like I journeyed together with you whilst reading this moving story. It almost got me teary-eyed. His life lessons as a parent and as a husband are what struck me the most. Thank you so much for sharing such a heart-warming story. You are definitely blessed and am sure your father must be very proud of you for becoming such a wonderful person as you are.