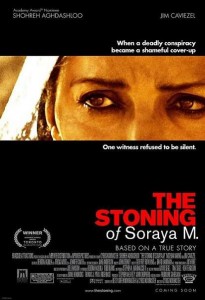

One of this year’s most powerful dramas, “The Stoning of Soraya M.,” has tremendous implications for global audiences immersed in both the movie’s story arch and the political situation unfolding in Iran this summer.

One of this year’s most powerful dramas, “The Stoning of Soraya M.,” has tremendous implications for global audiences immersed in both the movie’s story arch and the political situation unfolding in Iran this summer.

The film was adapted from the 1994 international best-selling exposé by French journalist Freidoune Sahebjam (played by James Caviezel). At the outset of the story, Freidoune’s car breaks down in the small Iranian village of Kupayeh. The mechanic, Hashem, initially reluctant to work on the car, agrees to fix it so that the journalist can make it to the border before dark. A woman in black follows Freidoune around, watching as he sips his tea in a local café, and finally captures his attention with a crumpled note that holds a map to her house and a human finger bone. The village’s mullah (Ali Pourtash) and Mayor Ebrahim (David Diaan) offer a greeting to the new stranger that barely masks their fearful, menacing postures.

The woman in black is Zahra (Shohreh Aghdashloo), a grieving aunt compelled to share her deceased niece’s story. Once Freidoune’s tape recorder starts, the audience is immersed in the narrative of Soraya (Mozhan Marnò), a battered wife and mother of four, facing enormous pressure to grant her abusive husband Ali (Navid Negahban) a divorce. Soraya refuses the divorce, citing her inability to care for two young daughters if Ali leaves her with no income and takes their two sons to the city. Eager to see his wife make money so that he can marry his new 14-year-old love interest, Ali negotiates a job for Soraya – housekeeping for the newly-widowed Hashem.

The mullah, a corrupt religious official with plans for his own gain, is then pulled into a corrupt plan by Ali: together, they frame Soraya for adultery, citing a “smile” exchanged between Hashem and Soraya. Though Soraya maintains her innocence until the very end, she is convicted by Mayor Ebrahim and sentenced to a public stoning by her village.

Amnesty International initiated a campaign last year to end stoning in Iran, citing the imprisonment of “Eleven people in Iran – nine of them women… waiting to be stoned to death on charges of adultery.” The organization also notes that women are particularly at risk for punishment by stoning, since “Women are not treated equally with men under the law and by courts, and they are also particularly vulnerable to unfair trials because their higher illiteracy rate makes them more likely to sign confessions to crimes they did not commit.”

The web-based media outlet Iran Human Rights Voice supports this action and argues that the victims of stoning are subject to gender and class bias, as “Women who have been stoned have been from poor and families or were women who were unable to divorce. These women were either married to husbands who were addicts, or were subjects of domestic abuse, or their husbands had attempted to marry multiple women… this kind of punishment has been one which was directed exclusively against women, but which has now begun targeting men in order to spread the atmosphere of fear, terror and panic in Iran.”

New York Post columnist Abby Wisse Schachter notes that,

“The brutal murder of Neda Agha-Soltan, shot dead in the street for the ‘crime’ of getting out of her car, even moved President Obama to finally condemn the Iranian regime’s crack-down. Neda has become a martyr for the cause of liberty and women’s rights. That resonates with The Stoning of Soraya M. because at its core is an innocent woman brutally murdered by an oppressive and tyrannical authority.”

The film has been banned in Iran, despite receiving accolades at the Toronto Film Festival and winning the 2008 Audience Choice Award, as well as being a runner-up for the festival’s People’s Choice Award.

Though it has received much negative press for its extended scene of violence, bloodshed in the film’s climactic stoning scene is far from gratuitous. Dressed in white, Soraya is buried up to her waist and left to struggle against hurling rocks thrown first by her father, husband, and even her two sons. The patriarchal implications of this are undeniable – tried and convicted by a closed jury of men, she is then viciously assaulted with rocks aimed at her head and torso. None of the women cast stones at Soraya, but instead tremble in fear at the sight; after all, their lives are just as vulnerable and subject to the same torture solely for being women.

With strong storytelling and an important message on women’s rights in Iran, this is a must-see for audiences in search of global perspectives on human rights violations and the necessity of reforming international torture practices.

One thought on ““The Stoning of Soraya M.”: a review”

Comments are closed.