Why start a journey if you know you’re going to fail? Why struggle against insurmountable odds when you’re doomed to lose?

The answer is simpler than you think: Because maybe – just maybe – it will turn out differently this time.

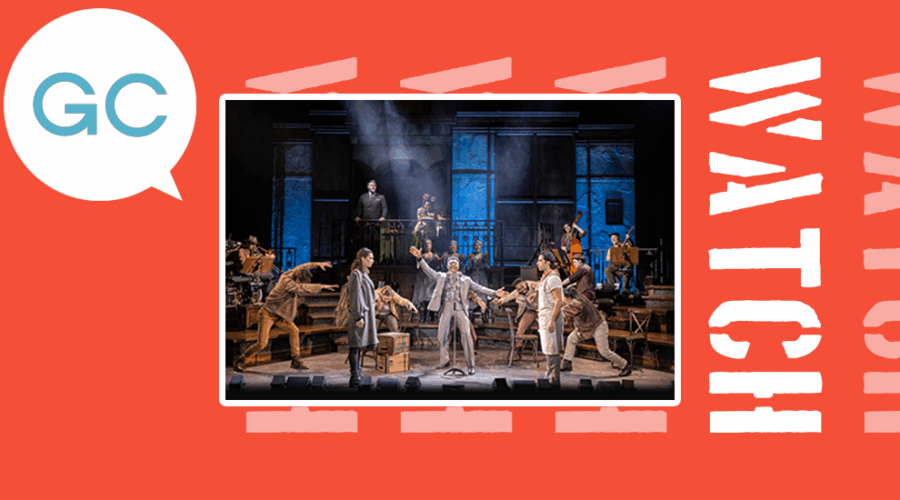

That’s the message at the heart of the 2016 musical Hadestown. This retelling of the Greek tragedy of Orpheus and Eurydice was first performed in 2006, and later turned into a concept album in 2010. It wasn’t until it premiered off-Broadway in 2016 that the show began to earn the acclaim it has now, premiering on Broadway in 2019.

The world that Orpheus and Eurydice inhabit is similar to our own. Hot summers and cold winters have led to famine and suffering. Spring and fall are but distant memories. Orpheus, the son of a Muse, has learned he can make flowers grow with a specific song and believes he has the power to make spring return, if only he can finish it.

Eurydice is world-weary and jaded, but Orpheus’ earnestness slowly wins her over.

Hadestown focuses on their love story, set amid prevalent themes of climate change, the dangers of unchecked power, and workers’ rights.

Hermes narrates the show, explaining that the weather has gone mad as a result of Persephone staying in the Underworld with Hades for too long. “It’s either blazing hot or freezing cold,” as the characters sing in “Any Way the Wind Blows.” The story of Hades and Persephone is another tale, and one of the primary love stories of Greek myth. But Hadestown puts its own spin on the story, showing discord among the two gods. Persephone is depicted as a drunk, while Hades has lost sight of all that matters, walling himself off inside a city – the titular Hadestown.

Persephone must spend half the year on the surface to balance out the weather, but even when she returns, Hades doesn’t allow her to stay for long. In “Way Down Hadestown,” he comes to collect her before summer ends. Persephone objects and tells Hades, “You’re early.” He replies, “I missed you.”

Hermes begins the show with a warning. In the first song, “Road to Hell,” he sings, “It’s a love song! / It’s a tale of love from long ago/ It’s a sad song! / But we’re gonna sing it even so.”

In the original myth, Eurydice dies from a snake bite, and Orpheus goes into the underworld to retrieve her. Hadestown changes things up. Eurydice meets Hades, who tells her she can have all the food she wants if she comes with him. Starving and afraid, she agrees.

Hadestown is a land of labor and toil, a city of metal and electricity isolated from the rest of the world. The workers there are nameless, faceless entities, doomed to toil away for eternity. In Way Down Hadestown (Reprise), Eurydice asks if the workers can see her. The Fates respond, “They can look / But they don’t see / You see, it’s easier that way.”

The workers labor under the guise of freedom, losing their own identity to their work, a clear criticism of modern capitalism.

The symbolism becomes even more blunt several scenes later, when Orpheus sneaks into Hadestown to find Eurydice and bring her home. In one of the most striking scenes of the play, the workers catch Orpheus and present him to Hades, who says, “Young man / I don’t think we’ve met before. / You’re not from around here, son. / Don’t know who the hell you are, but I / can tell you don’t belong. / These are workin’ people, son / Law abiding citizens / Go back to where you came from / You’re on the wrong side of the fence.”

It’s hard not to draw comparisons between the current US administration and Hades’ behavior. His constant emphasis on “protecting” his workers and declarations of who belongs where allude to a certain president, highlighting the absurdity of such beliefs. The earlier song “Why We Build the Wall” and its references to “keeping out the enemy” make it even more apparent.

Persephone recognizes Orpheus and asks Hades to let Eurydice go, reminding him that the love Orpheus and Eurydice have is something she and Hades once shared. Orpheus’ song convinces Hades, but under one condition: Orpheus must walk ahead of Eurydice and never turn around to check that she is following him.

He has to trust in her and in their love for one another. If he turns around to look, Eurydice will be forced to return to Hadestown, never to leave again.

The workers of Hadestown watch the exchange happen and begin to believe they deserve more out of their lives, placing their faith in Orpheus. They sing together in “If It’s True,” declaring “I believe that we are many / I believe that they are few.”

Orpheus departs, Eurydice in tow, but what happens next is what was always going to happen.

He turns around to check. Despite the consistent warnings from Hermes (and the knowledge of what happens from the original story), it’s still a shocking moment. In the song, “Doubt Comes In,” the audience sees Orpheus begin to struggle against his own thoughts. The loneliness and solitude wear him down.

The song is particularly poignant, as even while Orpheus sings about his own doubt, Eurydice is there, in the darkness behind him, singing reassurances. “Orpheus / You are not alone / I am right behind you / And I have been all along.”

The stage lights dim, and a spotlight shines on Orpheus and Eurydice, isolating the rest of the scene. Only those two characters are illuminated. There’s a moment of fleeting happiness, of joy, as the two lovers are reunited, followed by the crushing reality that they will be forever parted. “It’s you / It’s me / Orpheus / Eurydice.” In one production of the show, Eurydice says, “You’re early,” to which Orpheus answers, “I missed you.”

What appears on the surface to be a tragedy is instead a story of love and hope

This exchange is a mirror of the exchange between Persephone and Hades when he arrives to take her back to Hadestown. It further cements the parallels between the two couples, but carries a tragic note, as the characters know that is their last exchange.

Orpheus, despite his determination and love for Eurydice, fails in his quest. He loses her forever. And the people of Hadestown who had looked to him as a figure of hope, believing that if he could succeed, so could they, also lose hope. The penultimate scene could have been one of joy, suffused with the love of the two characters. Instead, it’s a tale of heartbreak.

It’s the ending the audience knew would happen going in, and echoes Hermes’ words: “To know how it ends.”

But the final scene of the show hints that, perhaps, it isn’t the end. Persephone arrives to the surface earlier than expected and announces that it’s time for spring. And we see Eurydice once more speaking her first words to the audience. It’s the shift in the timeline that spells hope. If spring is coming, then Orpheus’ efforts weren’t in vein. It also means Eurydice is never caught in the storm and forced to make a choice in “When the Chips are Down.”

It implies that, since the previous retelling of the story, Orpheus brought the world back into tune. And that the retelling the audience is watching is the last time it will be told; the situations and circumstances that culminated into tragedy are no longer in play, and the story of Hadestown will finally end with the triumph the characters deserve.

As Hermes says in the final reprise of Road to Hell, “’Cause here’s the thing / To know how it ends / And still begin to sing it again / As if it might turn out this time / I learned that from a friend of mine.”

What appears on the surface to be a tragedy is instead a story of love and hope. A story of encouragement. Hadestown tells the audience to continue hoping and struggling against the impossible. It practically screams that hope is not lost until we give up; that as long as at least one person is fighting, there’s a chance at a better future.

At a time when climate change is ravaging the environment, when seasons are vanishing and temperatures are reaching new extremes, it’s easy to feel hopeless. When fascism is on the rise and men who care for nothing except their own pockets and hedonism lead the world’s superpowers, fighting feels futile. Hadestown is oddly prescient, almost prophetic, considering the lyrics were written before Trump and his like-minded cohorts rose to power.

The warnings of the show feel more relevant than ever. Hades’ obsession with power, with building a wall to keep out “the enemy,” makes it easy to believe Anais Mitchell met with the Oracle at Delphi before taking the to Broadway.

But don’t forget Orpheus’ words of hope, as he raises a toast: “To the world we dream about / And the one we live in now.”