In the early 2000s, Venezuela was living an extensive oil bonanza. With Chávez in power, expenses were also increased when granting bonds to part of the population, making investments in projects that were abandoned over time and allocating aid to allied countries.

The price of oil in 1998, when Chavez won the election, was $11 a barrel. The following year, it was already at $14, skyrocketing in 2008 into $88. In 2010, when there was production close to 3 million barrels per day, it was situated at more than $100.

During the oil boom, the state received 700 billion dollars due to exports. At the same time, the country began to go into debt. For the year in which Chávez assumed power, the debt in bonds of PDVSA and Venezuela amounted to 19 billion dollars, and by 2013, the year in which Chávez died, it exceeded 60 billion dollars.

The financial fall of Venezuelan oil

According to the data managed by OPEC, Venezuela closed the first half of 2019 with 742 thousand barrels of oil per day, continuing with a fall in production. This year’s figures have been historical for one of the world’s largest producers, which in 2018 left its position in the top 10 of the countries with the highest exports in the world.

The downward trend has been observed for a decade, but with a daily production of more than 2 million 500 thousand barrels, the figures did not seem alarming. There was no such sharp decline since 1985, when production was just over 1 million 600 thousand barrels per day, production equivalent to that handled in 2017.

In recent reports, Venezuela is placed below Colombia, which had never achieved greater production than Petroleos de Venezuela. Other countries in the region such as Argentina and Ecuador have remained stable, while Brazil has presented a fairly steep rise since 2013.

Venezuela depends economically on oil, with an almost exclusive export of the product. Despite having the largest hydrocarbon reserve, the government’s unsuccessful investments have caused debts to increase and suppliers are forced to reduce their work until payment is received.

The South American nation owes about 70 billion bonds in foreign currency, but Venezuela also owes credits to countries such as China and Russia, which would add more than 180 billion dollars. With this panorama, the Maduro government has fallen behind in payments, and continuing the default could imply a series of international lawsuits.

The sanctions on Venezuela

In early August 2019, President Trump imposed executive sanctions to increase pressure on the Maduro government, extending the sanctions that have been applied to individuals related to the Venezuelan state.

With this action, the assets of the Venezuelan government and institutions dependent on it are frozen. Trump said he took the measure in the wake of the “continued usurpation of power,” the violation of human rights, the restriction of press freedom, arbitrary detentions and actions against Juan Guaidó, who has been recognized by some 50 countries around the world as interim president.

Previously, the Trump administration had decreed measures against more than one hundred officials related to Nicolás Maduro, and this new decree means an advance to pressure Chavez’s successor, after years of an economic, political and social crisis that has hit the Venezuelan population.

The letter sent to the chambers of the Congress establishes that the assets of the Government of Venezuela present in the United States are blocked, without the possibility of exporting, transferring, paying, negotiating or withdrawing.

The national company PDVSA had already suffered sanctions in the past, which helped increase the collapse of Venezuelan oil production. These new measures include state entities and political subdivisions.

The announcement also contains the list of blockages towards people established by the secretary of state and the secretary of the Treasury. In addition, business with Venezuela by Americans is prohibited. The order involves the exemption for Federal Government issues and transactions related to the provision of humanitarian aid, such as food and medicine.

This sanction represents the first of its kind in more than 30 years in the area, and it intensifies the pressures that have been exerted against the State for months, bringing measures for a total economic embargo. So far, it is the strongest sanction against Venezuela and puts the country in a position similar to Cuba, Iran, North Korea and Syria.

The decree came a week after the US president mentioned that he was considering the possibility of carrying out an economic blockade on Venezuela. This threatens to punish those who run business with the Venezuelan state, which would lead to isolation.

The measures against Petroleum of Venezuela

PDVSA’s cash flow has been compromised by the sanctions imposed by the United States Department of the Treasury at the beginning of the year. The measure blocks approximately 11 billion dollars from exports and freezes 7 billion dollars in assets.

The penalty restricts the import of US fuel to Venezuela and prohibits the export of oil from the South American country to the United States. The measures compromise an already affected gasoline consumption in Venezuela and increase the production difficulties of the oil industry.

So far, the United States is one of the most important customers of PDVSA, because the Venezuelan hydrocarbon has particularities that fit the country’s refineries. It is one of the largest consumers in quantity and was also the only one to pay debts in cash and on time.

What is the scope of the sanctions?

Trying to isolate Maduro also creates an economic fence that aims to move oil buyers away from other countries such as China, Russia and India. The sanctions prevent commercial operations with Venezuela, and for not being marked, some clients begin to move away.

Shortly after the sanctions by the United States, one of Venezuela’s main allies stepped back. China National Petroleum Corp canceled the purchase of Venezuelan crude to avoid international sanctions. It is not yet specified whether the suspension of the shipment of 5 million barrels of the hydrocarbon will represent a temporary or definitive interruption.

Turkey’s bank Ziraat Bank also turned its back on the Maduro regime. The financial institution closed the account with the Central Bank of Venezuela that was used for imports, making money movements and making payments from suppliers.

International companies, which still survive in a Venezuela in crisis, must ensure that they do not violate the laws. With this, many transactions may be at stake, due to the increased risks of having links with the regime.

Private companies can continue their relationship with foreign actors, so the embargo is not total. However, during any trade, it should be clear that they are not an intermediary of the Venezuelan government.

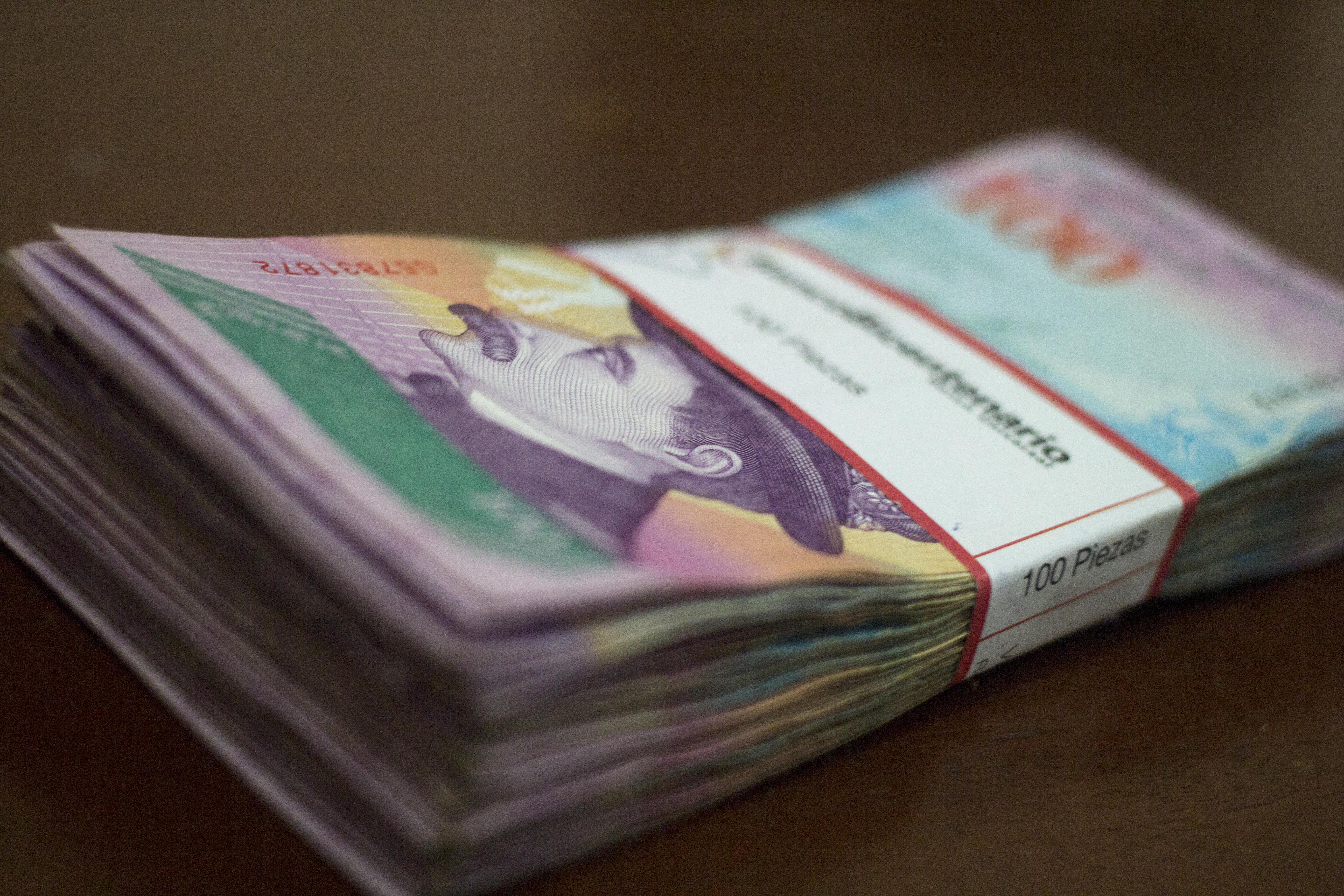

Image credit: Toni Rivera