A rich rebel from a wealthy family breaks down all governing norms. He shocks his competition by doing everything you’re not “supposed” to do, all while wielding a new medium they don’t fully understand. Finally, in record time, he has completely taken over the thing they once thought was theirs to always have.

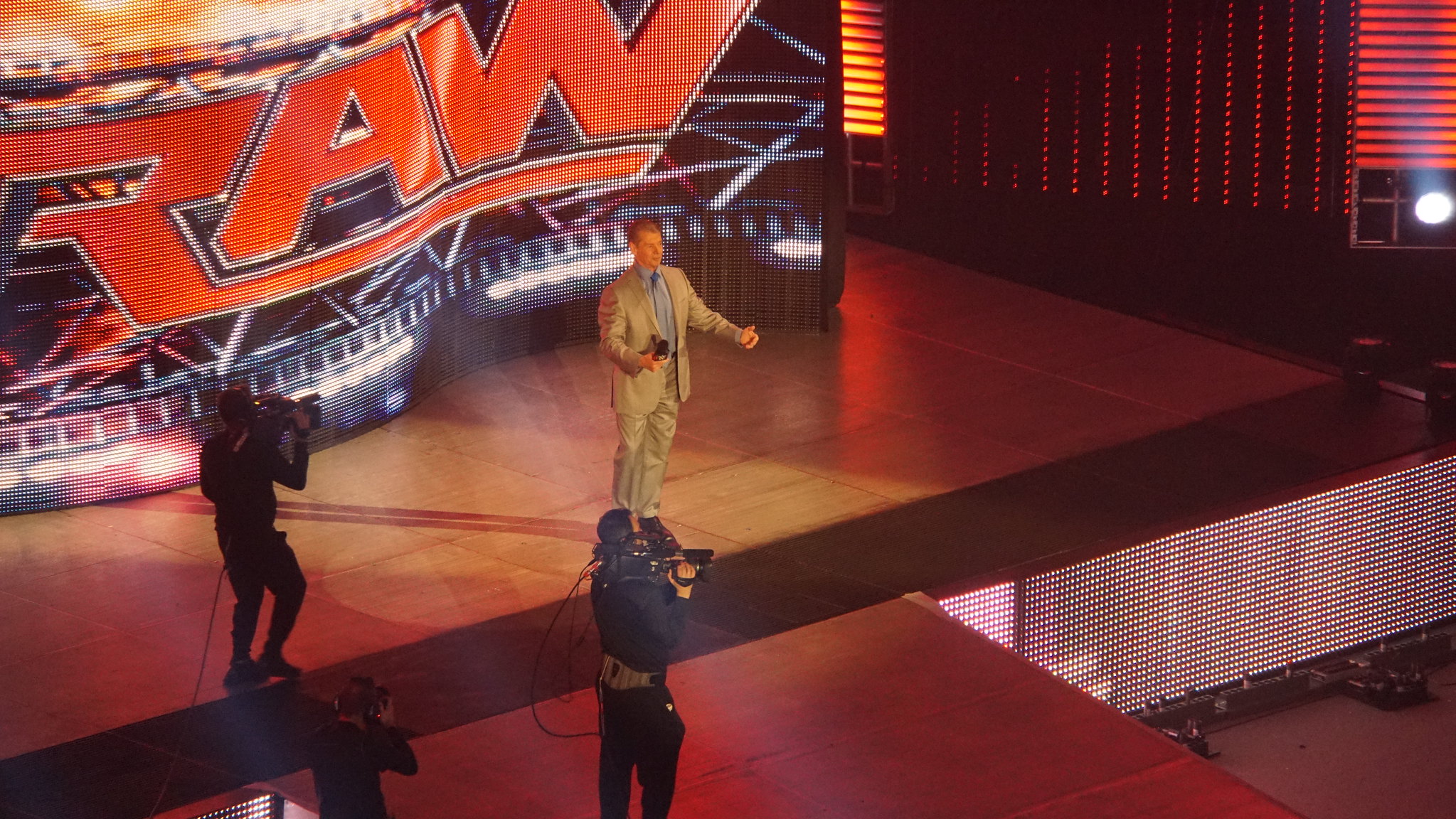

When you read that, no doubt you probably instantly think of Donald Trump’s ascension in politics and his takeover of the Republican Party. But I’m not actually talking about Trump there, even if it’s a bit eerie how close the description is. In fact, I’m talking about Vince McMahon, the owner and CEO of World Wrestling Entertainment. Many people, especially those on the younger side, probably aren’t aware, but WWE wasn’t always the only wrestling show in town. In fact, the landscape of the sport was radically different no more than thirty-five or so years ago. McMahon just took it over with a powerful force.

I was aware, somewhat, of McMahon’s national expansion in the 1980s, but never knew the details until I read Tim Hornbaker’s excellent Death of the Territories.

Before the ‘80s, the wrestling world in America was carved up into territories. Those territories usually compromised of several states or one of the bigger states, and each had their own federation that was owned and operated by a promoter. It was all kept in check by the National Wrestling Alliance (NWA), a governing body that was created to self-regulate the industry. In reality, it was a way for the rich families who founded these territories years ago to keep a monopoly on the business. It managed to keep squabbles and tensions between them all in check so that the system that had been created some forty or so years ago ran smoothly.

“Invasions” into territories happened, but they weren’t as dramatic as the word conjures. Usually it happened when one promoter was in a lull in business and another could smell the blood in the water and booked some shows where they weren’t supposed to. It ended with some arguing, handshakes, and profits exchanged. In extreme cases, one promoter buying out another and absorbing their territory while the exiting promoter got a nice payday on his way out. It was a perfect system, at least in theory, until things did start getting very dramatic, very quickly.

We often make fun of Trump for his tweeting. It’s almost hard not to. While I never subscribed to this idea that Trump is some secret genius, he has figured out something that none of his opponents really have. People want simple, quick answers to everything, usually on the fly. Clearly, that’s a sad component of modern life and politics, but it’s true all the same. While the 2020 Democratic hopefuls are still out trying to give complex answers to even more complex questions, Trump can fire out a single zinger tweet and people feed on it for days.

Similarly, in the mid-80s, Vince McMahon was the only one to see the true potential in another piece of new technology: cable television.

McMahon bought the WWE (then WWF) from his dying father in 1982 with one thing in mind, something that no one had dared attempt before: a national expansion of his territory. The WWF was the New York territory and had always been one of the most profitable ones due to its immense size and tight management. If you broke out there you pretty much had it made for a little while (despite the fact that the ‘New York style’ of wrestling was considered too over the top and gimmicky by a lot of wrestlers, especially those South of Mason-Dixon line). But McMahon wanted to break out everywhere, no matter what.

Just a few years earlier, this probably wouldn’t have been possible. One reason it could happen was because the NWA wasn’t nearly as united as it once had been as squabbles between current members coupled with the retirement or death of key leaders. While the WWF was no longer part of the NWA officially, McMahon’s father, Vincent James McMahon, still largely upheld the NWA’s status. Partially due to his friendships there and respect of tradition, but also because he knew had someone attempted a nationwide expansion, the organization would shut it down any way possible, through money, negotiation or old fashioned bloodshed.

Now, though, due to a weakened regulatory body, McMahon easily took phase one of his plan in buying up the top stars from various promotions. Hulk Hogan, the iconic wrestler that kickstarted the ‘80s wrestling boom, was actually groomed and trained in the American Wrestling Association (AWA) out of Minnesota. In the greatest talent raid in wrestling history, McMahon bought everyone who was “over” with any territory.

But it was cable television that was the true coup.

Like Trump uses Twitter so effectively now, McMahon made his product more television friendly. Traditionally, wrestling was a live event sport. The big promotions had their local television programs, but it was little more than advertisements to get you to the arenas. Go back to any wrestling program from the ‘80s that you can find, compare it to the WWF’s and it’s almost like watching something from two decades apart.

McMahon used the vast resources that the company had garnered to not just buy talent, but TV time. With the new ability of cable, now his shows could be broadcast into many rival territories, then he would swoop down and run live shows, usually with the stars other promoters had built in those same places.

It didn’t go unnoticed. Other promoters and NWA members threatened McMahon, tried to bury his product to their crowds, improve the look of their shows, run counter shows, and some even tried to emulate his expansion. But it was largely too late, and they could never muster a united front.

Eventually, McMahon took over. He either bought out all the old territories, or just let them starve as his WWF became a national touring brand going where it pleased, when it pleased. The only one who could ever rival it was Jim Crockett’s WCW, that was later purchased by Ted Turner and then, finally, bought by McMahon 20 years later to complete his total takeover of the wrestling world.

The story is obviously more complicated than all of this, but I will refer to Hornbaker’s book if you want all the nitty gritty (and trust me, there is some truly gritty details there). But for our analogy, you have to see the parallels here between McMahon and Trump.

Think about not just how Trump bulldozed through the 2016 Republican primaries, but how he did it with such reckless abandon, and then think when he did win the primary, and eventually the general election, how quickly the conservative world centered around him.

Just like McMahon and his WWF brand became wrestling, Trump has essentially become the Republican party, he has become the essence of conservative America. He did it his way, on his terms, and no one seemed able to stop him. The GOP couldn’t unite against him to push him out of the party, then the Democratic party couldn’t unite enough to stop him from the Presidency. And like McMahon, it’s really not enough for Trump to just own some of it; he needs it all. Trump wants to become politics. Hell, at this point, he might have already succeeded.

Almost forty years later, the WWE is still wrestling. Yeah, there’s been a resurgence in the independent circuits, Japanese wrestling, and now the All Elite Wrestling has had a big launch, but McMahon still rules the “sports entertainment” arena. If you want to get the national exposure, the good pay, that’s where you need to be. Even if AEW takes off, too, his brand is still going to be a constant, never ending presence. His children already play a huge role in the company (his son is wrestling now in a major storyline as I write this), primed and ready to take the McMahon name onward when he does die.

What does that say about Trump and national politics? Well, metaphors are metaphors, and wrestling isn’t politics, even if the latter is beginning to look more like the former every day. But I won’t be surprised if Trump’s brand is as equally as hungry as McMahon’s, and that shadow may be cast for a very, very long time.

Photo: Miguel Discart