The EpiPen is one of the most brilliant lifesaving medical developments of recent years: Few other medications and devices can have such an instantaneously dramatic effect. Americans with severe allergies that can lead to anaphylaxis and death carry EpiPens in their purses, cars, and school bags, dutifully replacing them when they expire — key, as patients may not get an adequate dose of epinephrine from an outdated autoinjector. In multiple states, schools are required to stock them.

It’s a critical lifesaving device with unbeatable market penetration: The medications involved and the autoinjector are so specific that they’re nearly impossible to replicate as a generic while still respecting Mylan’s patent, and the company knows it. The only other thing that comes close might be proprietary vaccines, like the HPV vaccine — also lifesaving, also critical, and also highly profitable, whether manufacturers are selling it directly or licensing it overseas.

When the price of EpiPens abruptly skyrocketed from $100 for a two-pack to $600 for the same two-pack for a device that costs approximately $30 to make, people were furious. It felt like Turing Pharmaceuticals all over again, with a firm that has a stranglehold on the market effortlessly flexing its weight. The hue and cry forced the company to announce that it would also produce a ‘generic’ for half the cost. Scathing commentators say it’s just capitalism and a conspiracy of Big Pharma, while others express grave concern about the accessibility of lifesaving medication, especially for low-income people in the US, some of whom lack insurance or are underinsured.

Except, wait a minute. The problem with the entire EpiPen debate is right there in the last sentence of that paragraph. Did you catch it? I’ll run it by you again.

…some of whom lack insurance or are underinsured.

The United States is one of the few major Western countries that does not offer a national single-payer health care system. Instead, it has constructed an elaborate fantasy world where health insurance and health care are confused. Health insurance is not health care. It’s insurance. It is designed to provide financial coverage in a set of limited and specific circumstances to people who require health care services. Depending on how much people can afford to pay for premiums (‘Cadillac’ policies can cost $500 or more monthly for a single person), what they can access scales up or down accordingly.

Insurers decide which health care providers people can see, which tests and procedures they may have, which medications they should be allowed to use. People pay not just premiums, but copays for these ‘privileges.’ The entire heath care industry — and it is is an industry — is built around these concepts, massively inflating costs for procedures, medications, tests, durable medical equipment, and any other services provided to people who need health care.

EpiPen is a red herring, a false emblem. The problem isn’t that a pharmaceutical company is profiteering off people who urgently need a very specific product, but that the system is constructed in such a way that this kind of profiteering is possible in the first place. The United States operates health care as a for-profit business, and thus it feeds this kind of activity. Meanwhile, people in other nations pay ‘below market value’ for US-manufactured medications because their governments have negotiated deals with pharmaceutical companies. This is treated like charity (as for example with HIV/AIDS drugs), but it’s not: Those people are paying something reasonably approaching a market value for medications that companies have invested billions of dollars in, and people in the United States are being bilked.

People overseas are often completely perplexed by the US ‘health care’ system, which is a labyrinth of overpriced goods and services, inexplicable insurance company denials, and ‘medical tourism,’ in which people travel overseas to get the basic care they need because they cannot afford it in the US. Or, in some cases, because the quality of care available in the US is inferior to that available elsewhere — the ‘greatest country in the world’ performs very poorly along a number of healthcare outcomes, including maternal/foetal health and neonatal mortality. The World Health Organisation wryly notes that maternal mortality is a ‘problem‘ in the United States — the country that invests untold gobs of money on an endless series of laws ostensibly designed to protect pregnant people and foetuses.

Health care and approach to same was a large issue in President Obama’s 2008 campaign, and the result was the woefully inadequate, gutted, dysfunctional Affordable Care Act, which only served to reinforce the notion that health insurance is health care. Any attempts at introducing national single-payer health care — which would be more efficient than maintaining an existing hodgepodge of government-funded entitlement programmes including Medicaid, MediCare, the entirety of the VA health system, and health care services provided to federal officials — have been roundly rebuffed. Senator Bernie Sanders tried it, and Jill Stein is including it in her campaign as well, but it’s treated as a fringe issue for laughable fringe candidates.

Meanwhile, the United States goes into conniptions every time the media report on new statistics about poor health care outcomes, or stratospheric increases in drug costs, or a tearjerker story about some poor person or another who’s been thoroughly abused by the health care system. People in the United States have an extreme difficulty making the connection between the personal, the institutional, and the political. The problem with EpiPen isn’t that the price rocketed out of reach for many patients, but that it’s being manufactured and sold within the framework of a system that actively encourages profiteering, treating health care as a service rather than a basic human right.

This year, Colorado has a single payer measure on the ballot — ColoradoCare. It’s currently polling incredibly poorly, illustrative of the incredible resistance many people in the US have to providing social services and improving the safety net even if it helps everyone. Though they may be told that it’s cheaper and less complicated to administer, that from a purely utilitarian and administrative perspective it makes sense, people in the US have surrounded themselves with a complicated mythology about single-payer and they’re clinging desperately to it even as their health care system crumbles around them.

Many of the same people voting ColoradoCare down are undoubtedly among those outraged about the EpiPen, but they can’t connect the dots between their actions and what’s happening in the health care industry — starting with the fact that it’s an industry, not a public service.

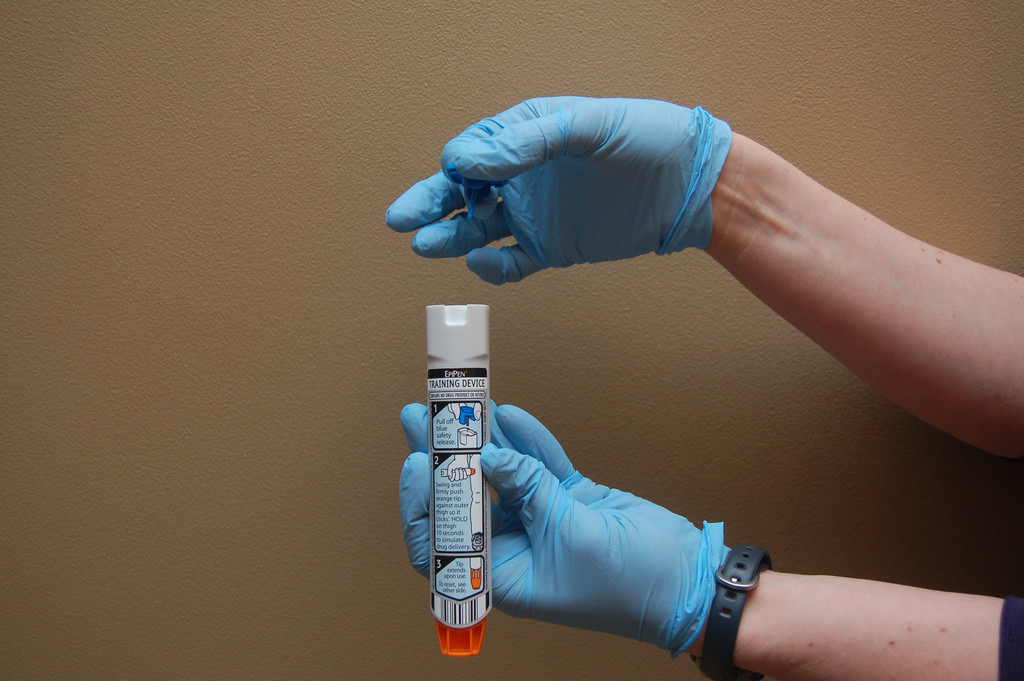

Photo: Greg Friese/Creative Commons