There is a reason the National Alliance on Mental Illness calls its outreach program “Ending the Silence”. When assessing our collective well-being and potential, mental health is a subject often pushed to the sidelines; sometimes recognized, rarely given the spotlight. As a 2013 article published in the Health and Human Rights Journal states: “…in both high-income countries and low- and middle-income countries throughout the world, mental health care is a low priority, receiving stunted budgets, inadequate resources, and little attention from government”.

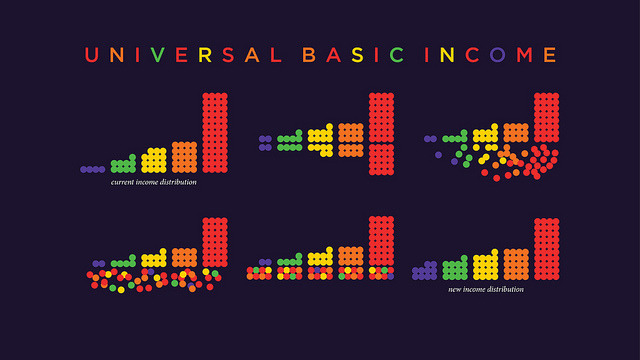

The old-but-new debate over a universal basic income policy is no exception to this trend. For those who are unaware, this proposal requires the government to provide a cash stipend to every citizen within its authority, with no strings attached and no questions asked; essentially a “free money” program. Academic economists have found a common thread which winds itself through the writings and speeches of everyone from Milton Friedman to Martin Luther King Jr., and can be traced back as far as the writings of Thomas Paine and Thomas More.

The economic benefits of such a seemingly radical policy are just beginning to trickle into the peripherals of the mainstream debate; its impacts on food security, education, and the federal welfare state are among the most evident, and are likely the first to come to one’s mind when thinking about this project. There is one facet of such a policy which is important, but typically relegated to footnotes or passing comments: how would a universal basic income, or UBI, affect the mental health of those who receive its monthly stipends?

Academia has already come to the conclusion that higher incomes lead to a healthier mind. A 2008 medical study notes the “well-documented association between low income level and frequent mental disorders”, and an article published in a prominent psychiatry journal found that low-income households “are associated with several lifetime mental disorders and suicide attempts”. Other studies have found a connection between poverty and substance abuse, mood and anxiety disorders, and psychopathic behavior.

None of this should come as much of a surprise; the American opioid epidemic is not a problem that the wealthy must struggle with, and anxiety disorders can be treated much easier when one has access to psychiatry, which isn’t free. For the super-rich, psychopathy can be a potential asset, when used correctly. It is the poor who predominantly struggle through these issues, and as of now, it is the poor who must find a way to deal with them; generosity and altruism are not enough.

Of course, I’m not going to deny the concoction of public facilities and welfare programs in the United States which already exist to solve some of these issues. But the failure of this system to prevent an opioid epidemic, bring the poverty rate below 10 percent, or stem the rise in mental health issues despite the size of its budget leaves much to be desired. This brings us back to UBI.

Journalist Annie Lowrey, who reported on a trial UBI program in a Kenyan village, wrote “There have been a handful of experiments…[but] no experiment has been truly complete, studying what happens when you give a whole community money for an extended period of time”. While the perfect trial period has perhaps yet to see the light of day, there have in fact been studies of basic income programs which study its effects in the long-term, with many of them making passing mentions of their effects on mental health.

In 1996, Elizabeth Jane Costello studied the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in North Carolina, a tribe which began distributing casino profits to each of its 8,000 members. Ten years after the program began, Costello not only found that rates of substance abuse had fallen and mental-health complaints dropped by nearly a third, but those who received the stipends when they were young continued to benefit well into young adulthood. As Costello writes, “…changes in a household’s permanent income can have permanent effects”.

The mid-1970’s “Mincome” experiment, a more well-known example of UBI in action, saw the Canadian federal government and provincial government of Manitoba distribute basic income checks to every resident of the town of Dauphin. Five years after receiving its “Mincome”, Dauphin saw its hospitalization rates tank, with the drop in admissions for mental health related problems being one of the largest contributors. Lowrey’s own study of UBI in Kenya found that there, too, mental health improved with income supplements.

It’s difficult in today’s political climate to make ethical arguments for certain policies; people make decisions as to whether someone is “deserving” of assistance, healthcare, etc. before getting into the details and logistics of assistance programs, which is where the disagreements lie. However, the UBI debate is not a typical debate. Across the political spectrum, a human rights case is being made alongside one concerning feasibility, and mental health fits in quite well with this discussion of human rights.

Martin Luther King Jr. wrote that a basic income policy “is not only moral, but it is also intelligent. We are wasting and degrading human life by clinging to archaic thinking”. Milton Friedman spoke of a guaranteed income which the poor are “entitled to”, while fellow Libertarian thinker Friedrich Hayek wrote that our “free society government” should offer “insurance against extreme misfortune”. While this misfortune may be financial, should we not consider mental health issues “extreme misfortune”, especially if they are ones which would require hospitalization, as those noted in the “Mincome” experiment?

The UN Declaration of Human Rights states:

Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including…sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.

I believe, as anyone would, that mental health issues are beyond one’s control as the Declaration states, and their alleviation is thus a human right as stipulated by the international community. A basic income program would not only alleviate poverty, but also depression and despair. As the “free money” debate evolves, we should keep in mind that the question of guaranteed income is not simply a debate about financial stability, but one of health and happiness as well.

Photo: Mike Ramsey/Creative Commons