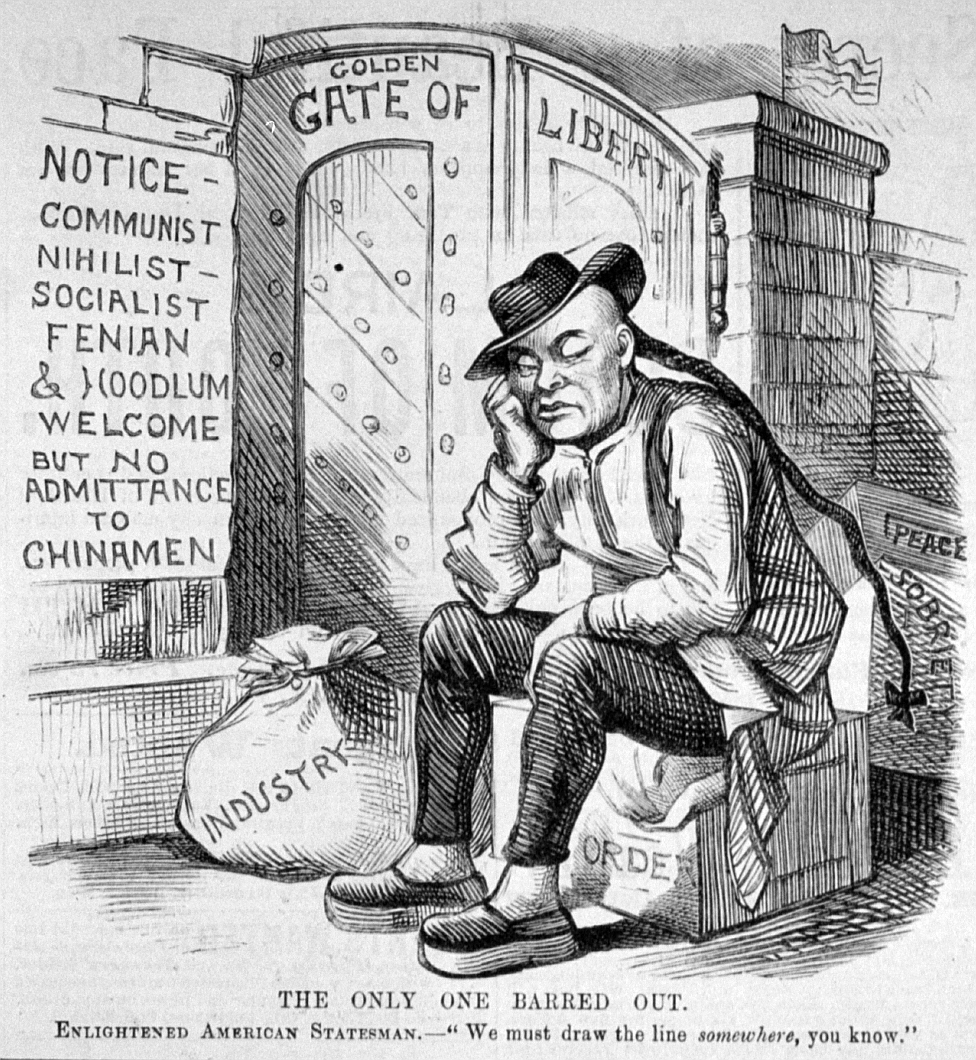

In 1882 America banned Chinese people from coming to America. It was the first time that America placed legislative restrictions and regulations on a group of people who sought entry into the United States based solely on their origins.

In what is known as the Chinese Exclusion Acts, those identified as Chinese laborers (a very open term) were stopped from immigrating to the United States. Not only were most Chinese people barred from obtaining citizenship, but their families, livelihoods, and dignity were torn apart.

The 1882 act, as well as subsequent renewals of the act, largely claimed to protect American jobs from Chinese laborers.

With growing anti-Chinese sentiment in America, the acts were also put into place to quell American attitudes over the animalistic “Chinamen” or “coolies” who were not only stealing their jobs but also harming American culture with their foreign ways, innate inhuman violence, and boroughs of ill-repute or “Chinatowns”. Chinese were both reviled and feared; assaults against Chinese immigrants was rampant and went unpunished; the majority of Americans viewed Chinese people as a threat to American economics and society. Chinese people were viewed as entirely incapable of assimilation into American culture.

In essence the Chinese were alien, un-American, and dangerous. Their presence on American soil was cause for alarm.

Before Trump signed the executive orders attempting to implement a Muslim ban, before Japanese-Americans were incarcerated during World War II, Chinese people in America held the distinction of being the “aliens from the east” most hated and discriminated against in the United States. And while the times and targets may have changed, the rhetoric stays chillingly the same.

To examine the decades of discrimination that the United States implemented against Chinese and Chinese Americans is to examine the era our current president wants to usher us into: an era of blatant racism and “enemy alien” mentality. The Chinese Exclusion Acts and the treatment of Chinese people, are not remnants of some dark past that America has entirely risen above. No, it is a part of our pedigree. Like it or not, xenophobia is in our red, white, and blue blood.

But the need to be better is also part of who we are.

As it’s been said countless times in countless ways since Trump took aim at Muslims and Muslim Americans, America cannot – must not – use its past transgressions against race and religion as a precedent for homeland protection.

We need only look back 74 years to see the striking parallels between where we were and where we are headed. While the Chinese Exclusion Acts may not be at the forefront of American consciousness, it is more vital than ever that we examine the acts to realize the dark history we are poised to repeat.

***

Americans (white Americans) didn’t always have a problem with Chinese people.

When California became a state in 1850, Chinese immigrants and laborers were celebrated as hard working “equals”. In 1852 the governor of California even “praised the Chinese as ‘one the most worthy classes of our newly adopted citizens.’”

However this sentiment was short lived.

Because many Chinese immigrants had to struggle to survive in America, very often working to send money home to their family, Chinese laborers (skilled and unskilled) were willing to work excruciatingly hard for almost any pay they could get. This meant that business owners and companies could get away with paying Chinese laborers far less than their American counterparts.

During the early years of the Gold Rush and the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad, Chinese laborers were tolerated if not briefly embraced. Because Irish workers rallied for higher wages to build the railroad, Chinese laborers became the workers of choice, making up 80% of the railroad workforce.

However, once the railroad was completed in 1869, anti-Chinese sentiment flared up with a vengeance. California’s population quickly increased and with that came an increased competition for jobs. With the banning of slaves in the state, many feared that Chinese immigrants would become the new “slaves” – willing to do the same work as white Americans for less pay, thus stealing jobs away.

In the 1870s the anti-Chinese movement spread beyond the threat of job security for Americans, and became blatantly racist attacks on Chinese humanity and morality.

Labor organizations that aimed to unite workers across race, creed, even gender actively excluded Chinese laborers. Organizations like the International Working Man’s Association, the Workingman’s Party of California, and the Knights of Labor “demanded the right to ‘white men’s wages,’ not the ‘starving slave wages’ fit for the Chinese” (Kwong and Miščević, 92).

The Knights of Labor said that the Chinese, “bear the semblance of men, but live like beasts…who eat rice and the offal of the slaughter house.” They went on to call them “natural thieves” and “referred to all Chinese women as ‘prostitutes’” (Kwong and Miščević, 92).

By 1877 “The Chinese Must Go” was a rallying cry, with increasing hostility and violence toward Chinese and Chinese communities. After much legislative and organizational rumbling and fumbling regarding the restriction of Chinese people entering and working in America – including the Page Act which aggressively limited the number of Chinese women entering the United States through an intense interrogation process – the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was passed.

The act, which was put into place for 10 years, then renewed for another 10 years in 1892, then renewed indefinitely in 1902, barred all entry of skilled and unskilled Chinese laborers, but allowed merchants, scholars, teachers, missionaries, and government officials. If a Chinese person was living in the US, left, then tried to regain entry, even if they were legally allowed residency, it was not guaranteed they would be re-admitted. Due to the fear of not being able to re-enter once they left many Chinese-Americans opted never to leave the US, thus forever separating them from their families in China. In turn, many Chinese-Americans who left the US and then tried to gain re-entry were denied. Countless families were torn apart.

With wives and children in China and a large number of Chinese men somewhat “trapped” in the US, it was not uncommon for Chinatown tenements to house mostly men who were unable to reconnect with the families they left behind. Even after the acts were lifted, many families could not reunite because they had either lost track of each other or had become completely estranged.

While Chinese immigration slowed to a trickle, and naturalization was made impossible, many still risked their lives to live in the US in order to escape war and poverty. Because relatives of documented Chinese-Americans were allowed to live in the US, generations of “Paper Sons” came about.

If a documented Chinese-American reported that his wife in China had had a child, then he would receive legal documentation for that child to reside in the US. That documentation could then be given or sold to an undocumented Chinese person, allowing him (or sometimes her) entry into the United States. The paper son would then have to entirely assume the identity on that documentation. If he married, his family name would continue to be his assumed family name in order to not arouse suspicion.

Entire family names were erased during the Exclusion era, with some Chinese-American families just now reverting back to their original names.

It was the hope that, aided by anti-miscegenation laws, the Chinese population in the west would be wiped out in a generation or two.

But beyond the hardships of entering the US, life for documented Chinese immigrants and Chinese-Americans was far from easy. It was downright dangerous.

Considered inassimilable, due to their different appearance, “heathen” beliefs and practices, and the “ghettos” they lived in, Chinese-Americans faced both social and institutionalized racism. They were just too different. Chinese-Americans were not allowed to own businesses, own land, or attend public schools. Work was hard, if not impossible to come by, as businesses that employed Chinese-Americans faced boycotts, riots, even arson.

Anti-Chinese riots in the west were the norm, with Chinese communities often being driven from their neighborhoods. While many Chinatowns are now seen as tourist destinations and pockets of quaint exoticism, Chinatowns were initially towns of segregation. Chinese-Americans had no choice but to live there.

In one of the largest Chinese communities in Butte, Montana, the Trades and Labor Assembly “endorsed a boycott of all Chinese and Japanese restaurants, tailor shops, and washhouses in January 1897” (Kwong and Miščević, 112). In the local paper they stated, “American manhood and American womanhood must be protected from competition from inferior races.”

Called “Mongolian hordes” stealing jobs from good, honest “Irish laundry women”, the situation in Butte was only one of many steps taken to expel laborers of Chinese origin from the American workforce. By 1910 it had worked. Chinese-Americans could only work for themselves in Chinatowns (laundry, restaurants) or by “doing domestic work for white patrons”.

Additionally, after the renewal of the Exclusion Act in 1892, or the Geary Act, it was required that all documented Chinese immigrants and Chinese-Americans had to carry photo identification at all times to prove they were “legal”. While some rallied that they should refuse to follow the “dog tag law”, many feared the punishment for being caught without identification. Chinese people caught without their documentation could be jailed, deported, or sent to a labor camp.

Generations of Chinese-Americans lived under these conditions; being considered inassimilable while never being given the opportunity to assimilate. It was race-based hatred pure and simple.

The Chinese Exclusion Act was finally repealed in 1943 – over 60 years after it was enacted – with the outbreak of World War II. The Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act of 1943, or the Magnuson Act, did not happen because of some upsurge of pro-Chinese sentiment, but because China became America’s ally in the war. It should be noted that 1943 was the same year that the internment of Japanese-Americans began.

While the Magnuson Act opened up a small percentage of Chinese immigration and the naturalization of some Chinese-Americans, Chinese people in America were still forbidden from owning land or businesses until the full repeal came in 1965.

1965. That was just over 50 years ago. If you are of Chinese-American descent, it’s very possible that the Magnuson Act affected you or your family. When Generation X was being born, Chinese-Americans were still legally second-class citizens.

Normalized anti-Chinese sentiment and Chinese exclusion was not that long ago. Yet it’s been largely forgotten, disregarded, or even romanticized by the American consciousness. While this is a shame for our nation, to forget our past, I’d argue it’s also dangerous for our future.

We have a president who seems determined to bar a group of people from America, keep track of those on American soil, all in the name of protecting Americans from the threat of a group of people who are viewed by our president and his followers as fatally un-American, inassimilable, and a threat to our safety and way of life.

I’ve typed those words and words like them over and over in this article. With the sentiments between the Chinese Exclusion Acts and the Muslim ban being so strikingly similar, it’s baffling to that one can be a “dark period”, a shameful part of American history, and one can be in the best interest of America.

If the president finds a way to move his executive order forward, and the travel ban is officially put into place, how long will it be before we realize how quickly we repeated our “dark” history? Is being non-white, non-Christian, foreign-born in America like being part of some sort of minority roulette? When will it be your turn?

Hopefully, with the blocking of Trump’s Muslim ban, we are witnessing the end of America’s tradition of alienating “others”.

Additional source: Chinese America, The Untold Story of America’s Oldest New Community, Peter Kwong & Dušanka Miščević. The New Press, New York, London, 2005.