I am not going to dig up the tweet lest it receive even more unneeded attention (we all know that attention is its own kind of currency among unpleasant troglodytes), but one of the funnier misinterpretations of the 2024 Summer Olympics opening ceremony came from a conservative guy who immediately decided that the “pale horse” (actually silver horse) during the proceedings was a symbol of French satanism. Other people pointed out that it was Joan of Arc, but who cares about actual art criticism when you can be loudly offended instead?

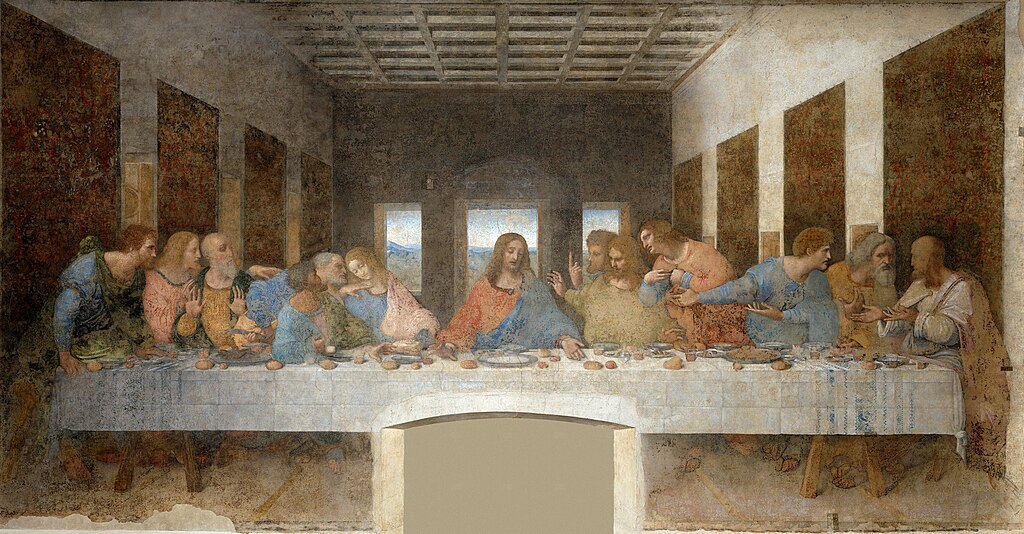

I’m not even going to bother pointing out a Greek bacchanal (get it? The Olympics originated in Greece), complete with Dionysus, being mistaken for a profanation of the Last Supper — though at the same time I think Leonardo da Vinci himself would have enjoyed the uproar.

The thing about arguing with ignorant people is that there’s rarely any point. If you try to introduce historical and artistic concepts to a conversation, they just take it as an insult. And they always manage to out-yell you.

Although I distrust collective outrage, I do think it’s satisfying to see the French inspire it. Most of the French artists I personally know, at the very least, enjoy disdain. Being misunderstood by idiots means you’re doing something right, etc.

Joan of Arc herself was pretty badly misunderstood in her time, and paid dearly for it. Now we just get angry Twitter threads. You can say that Western culture overall has improved on itself in that regard, even if a bunch of Christian nationalists badly want to drag us back to the days of witch burnings.

It wasn’t “The Last Supper.”

The blue guy rolling around on the table was supposed to be Dionysus, the Greek god of fertility and wine.

Get a grip. Seriously. pic.twitter.com/wzCJ95Agtb

— BRYAN SCHOTT – “The Evil That Destroys” (@SchottHappens) July 27, 2024

As a basic bitch at heart, I most loved a headless Marie Antoinette singing a song about stringing up aristocrats before the heavy metal band Gojira jumped in.

The older I get, the more I appreciate heavy metal, even if this should be the other way around. There’s something very pure about this genre, it gets away with more pathos than regular pop music.

I’m not nearly as angry as I was in my youth — I think a younger me might have been swayed by the religious criticism of the ceremony — but I am more relaxed, and for some reason, heavy metal can be very relaxing. There’s just something so primordial about it, it makes me think of ancient processes, tectonic plates shifting, the beginnings of time. Some of you have no idea what I mean, but maybe you will, eventually.

In one of William Butler Yeats’ more complicated and less famous poems, it is declared that “fair needs foul.” I couldn’t help but think of these words as I watched the ceremony and the subsequent, albeit now thankfully fading, scandal. Our most dearly held sentiments often exist to be exploded from the inside out. Religion wouldn’t hold nearly as much power if it didn’t play offense or defense. Neither would art.

Back in the 1980s, for example, many people were offended by Andres Serrano’s Immersion (Piss Christ). On the surface, it remains a purely provocative image — a photograph of a crucifix submerged in the artist’s own urine. There were protests and death threats and vandalism. As a child of a deeply religious mother, I was taught to abhor the image. Later, I just thought of it as juvenile and annoying.

But when I think about it today, it occurs to me that Jesus Christ is meant to be seen as the son of God, who walked among us. Who raised the lowly. Who embraced the foul. Serrano himself has said that he distrusts art as a message, but over the years, it seems to me that there is an intimacy between God and humankind that the image came to invoke, even if Serrano didn’t particularly want it to.

Serrano, it is often said, wanted to disrupt the pleasure of a spiritually comforting image, but the image can carry its own kind of comfort if you seek Christ as a human being, a being ensconced in flesh. The thing about art is that it often takes on a life of its own, after all.

Maybe this opening ceremony in Paris will take on a life of its own too. The outrage cycle moves on. But our relationships with art, and with God, are not static — at the very least, they are not meant to be, lest both art and God be dead.

And the French, in their usual, roundabout way, have shown us that this is not the case.

Image: Rumour Juice