Why does representation in books matter? This is something I have been wondering about for a long time, as I write Young Adult literature, primarily about disabled and queer teenagers, and am trying to get published.

Why does it matter that all teenagers, of whatever gender, sexuality, ability, colour, religion, race, class, and a million other marginalisations, see themselves reflected in the books they read?

Well, because it’s good to see people who look like you in media. It strikes deep chords. It contributes to self worth. It can bring about a deeper connection to one’s own community, or culture. I belong to several marginalised communities and am also interested in the intersections that people live in – for example, if they’re both queer and a person of colour.

I understand that my experience of the world is shaped not only by my marginalisations but also by my privileges – I am a white cis woman living in the United Kingdom, which confers certain privileges upon me.

We could all learn more by deepening our understanding of the experiences of others.

One of the ways in which we can all learn more about our privileges is to learn about those who don’t have them and that’s another reason that representation matters: for people not in those communities, reading about them engenders learning and brings about empathy. We could all learn more by deepening our understanding of the experiences of others.

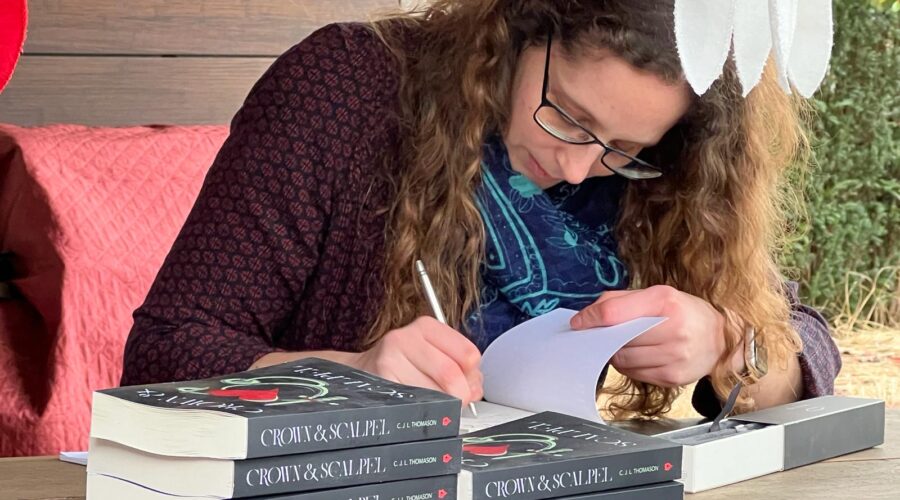

That is a long way of saying that although I personally am not blind like the main character in the book I’m about to review, I do think a lot about representation and the issues surrounding it, so I would like to think that I can give a good review. But I realise that I am not blind. Neither is this author, C J L Thomason, but it is clear that she has done her research. I’m not sure if she has used a sensitivity reader but it seems likely. The blind people in this book are well-rounded, well written, flawed characters, as all good characters should be.

I will also say that I generally don’t read fantasy novels so this one is a bit out of my comfort zone. However, this book’s world and world building really captured my imagination. For me I think it helped that it is recognisable as similar to our world, and that there are a few human characters.

I will also say that I generally don’t read fantasy novels so this one is a bit out of my comfort zone. However, this book’s world and world building really captured my imagination. For me I think it helped that it is recognisable as similar to our world, and that there are a few human characters.

However, this world is Elven, populated by elves. Elves live for centuries, unlike humans. Ambarenyll is already very old, but still pretty young for an elf. He is a doctor. He has a young ward and apprentice, Pallu. He is close friends with his brother, Faraiël, and their friends Arkèn and Raven.

In this world, these people live in the kingdom of Landaïla, which is ruled over by King Dohandrahel. He has a daughter, Jadaleyana, who is known as Jade. Most people in this world are Mane, but there is a small faction of people who are Darme. They have purple grey skin and black eyes and are clearly marginalised and treated in a racist manner. They have had rebel uprisings over the years, and now Jade and her soldiers fight small factions of them.

On one such trip, Jade is injured by Darme rebels and ends up at Amba’s house. She has a broken leg and injuries along her side, so Amba and Pallu treat her. Many of her soldiers are dead and she needs to hide, so she stays at Amba’s house.

He is blind. He was married and had a small daughter, but they were killed in a Darme fire thirteen years ago. This also left Amba blind and unable to practice medicine. It has taken him until now, and the fact that Pallu is nineteen and about to start studying medicine, to start working again. He used to be a skilled surgeon but he is still a skilled doctor, using his hands and knowledge of herbs and so on to treat patients. He also has access to some human medicine, like anaesthesia, from his mentor Thomas.

He and Jade don’t hit it off well. She is prickly and entitled; he is traumatized and sometimes difficult. But they start to build up a friendship and an attraction grows between them. I really liked the romance part of this book, as it seemed really natural and organic.

Jade has trauma too. Her mother and brother were killed by the Darme and she doesn’t get on with her father as he is difficult and angry. She flourishes while staying with Amba. But there are other forces at play, both Darme and other, that threaten her life.

She and Amba have to take off suddenly. I really liked this part of the book because it showed Amba’s strength and resilience and how he could fight even though he was blind. He learnt to ‘see’ his surroundings by using echolocation, which is explained really well. Other people don’t always realise to begin with that he is blind, and there are moments of prejudice when they find out, which seemed very real. They also ask stupid questions about his disability, which is something that every disabled person has had to deal with and which Amba dealt with in realistic ways – sometimes he was angry, sometimes he dealt with them graciously.

I also liked how Amba was sometimes angry with his disabilities, sometimes frustrated with himself, but mostly he managed to give himself grace and ultimately realise that he still had a lot to offer the world as a doctor and as a person.

I think this book is a brilliant example of the first one in a series: it sets up the world, it introduces the main characters and conflict, enough happens to keep it interesting, but there’s a bittersweet end that definitely paves the way for the next book. I would be interested in reading another, which is always a sign of a decent book for me.

I think it’s best to leave this review with a quote from one of the inspirations for it:

“Thanks for your diligence in portraying the blindness bit right. I’d say you’ve probably come closer than any other author I can readily think of. And yes, I can see you’ve done your homework.” – Daniel Kish, Founder and President of the World Access for the Blind and Visioneers, Pioneer and Expert in human echolocation