I’ve been writing recently about science fiction book recommendations and it got me thinking about sci-fi art – and some of the spectacular artworks which the genre has inspired.

Science fiction has a long tradition of exploring the human condition with depth and thoughtfulness, whether in books, television or film.

But it also has a lesser-known and equally rich artistic history. Sci-fi art not only influenced the space race of the 20th century, it has had a far greater cultural impact than many people realise – reflecting society’s hopes and fears, and helping us visualise the unknown. For all its future-facing speculation, this is a kind of art – and genre more broadly – that is deeply rooted in the present, shaped by the dreams and anxieties of its time.

Origins

The earliest sci-fi art is older than you might expect, going all the way back to 1831, when a new edition of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein was published with an illustrated frontispiece, showing Dr. Frankenstein recoiling from the monster he created. Frankenstein is widely regarded as the first ever science fiction novel, and while Theodore Von Holst’s frontispiece isn’t stylistically what we might now think of as sci-fi art, as the first published artwork illustrating a science-based work of speculative fiction, it has a good claim to the title.

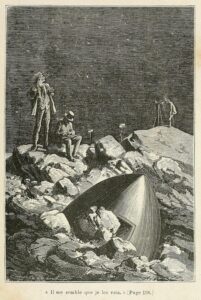

The Victorians took things further: think of Émile-Antoine Bayard’s illustrations for Jules Verne’s novels, for example, which featured early depictions of imagined technology, or the beautiful astronomical illustrations of Étienne Léopold Trouvelot.

The Victorians took things further: think of Émile-Antoine Bayard’s illustrations for Jules Verne’s novels, for example, which featured early depictions of imagined technology, or the beautiful astronomical illustrations of Étienne Léopold Trouvelot.

Trouvelot’s work wasn’t speculative per se, but here we can see the first glimmers of what future science fiction art might look like. We could even draw a line from the artistic works of Gustav Doré and Odilon Redon to H.R. Giger and Moebius, a hundred years later.

Pulp & print

If Victorian science fiction was concerned with scientific experimentation, ethics and exploration, it soon progressed into pulp fiction, which enjoyed huge popularity from the 1920s to the 1950s.

Science fiction magazines such as Amazing Stories – the first sci-fi pulp magazine, launched in 1926 – reprinted the works of Jules Verne, H.G. Wells and Edgar Allan Poe, as well as stories by amateur writers.

By 1938, when John W. Campbell became the editor of Astounding Science Fiction, writers such as Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, Arthur C. Clarke and other genre luminaries were starting to focus on space exploration and robotics, often taking a more literary approach. Campbell’s editorial direction defined what we now refer to as the Golden Age of science fiction.

A sensationalist branch of the genre also started to take shape, spearheaded by Weird Tales, which pushed boundaries even further. It explored ideas of body horror, mad scientists and erotic aliens, producing works which had a more surreal feel to them. The art of all these magazines is iconic today: brightly coloured, full of spacemen wearing bubble helmets, exploding planets and scantily-clad, voluptuous women in need of rescue.

But pulp didn’t just bring sexy aliens and bug-eyed monsters into our consciousness – it helped to create a visual language for sci-fi that we still recognise today. Think of Star Wars or Flash Gordon, for example, and many of the motifs trace right back to the pulp era, as do many of the clichés we associate with it.

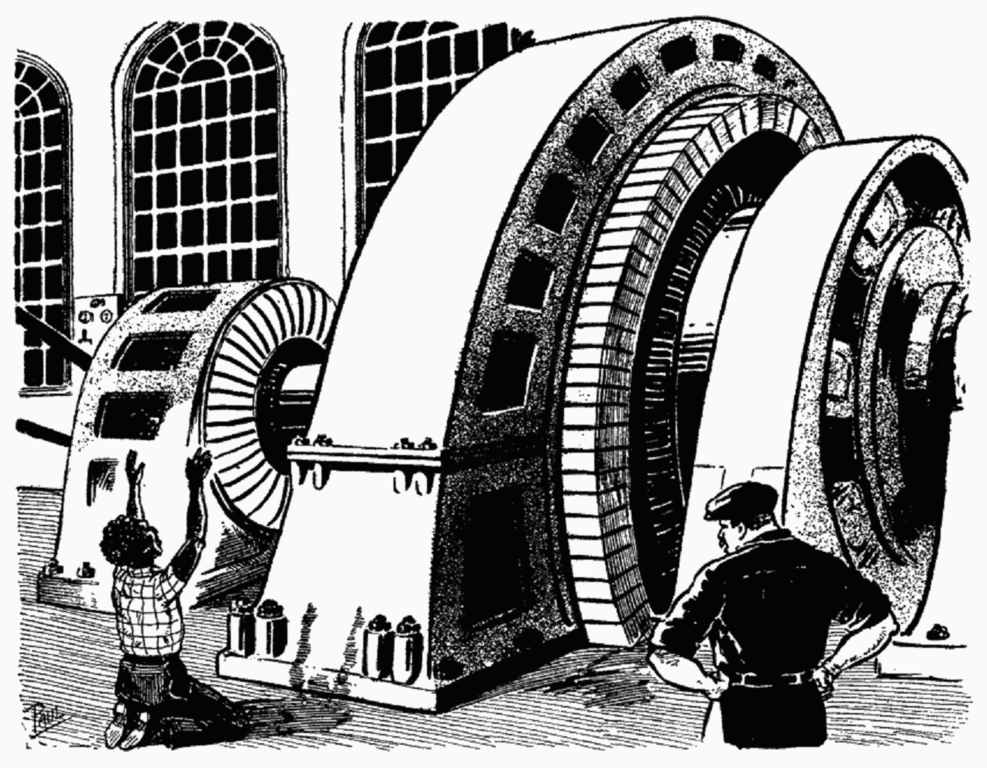

Pulp also helped to establish sci-fi as a mass genre with a dedicated fanbase, and laid the ground for later, more literary efforts to grow. Frank R. Paul and Virgil Finlay are probably the most famous pulp artists and their illustrations still look familiar now, even if you’ve never read a science fiction magazine.

The space age

The post-war era brought us the name perhaps most associated with sci-fi art, often described as the father of modern space art: Chesley Bonestell, the artist who helped to launch the space age and inspired not just NASA but a whole generation of scientists.

Bonestell was an architect who worked on the Chrysler Building and the Golden Gate Bridge. He painted meticulously realistic views of space scenes – whether of Saturn as viewed from one of its moons, or of the valleys and mountains of Mars – all based on the astronomical data of the time and intended to be realistic rather than speculative.

Many of his pieces were published in Collier’s Weekly and Life magazines. He went on to contribute to various science fiction films including 1950’s Destination Moon, one of the first serious attempts at cinematic realism, and 1953’s The War Of The Worlds.

So respected is Bonestell that he has both a crater on Mars and an asteroid named after him.

The 1960s-70s saw a shift within the genre towards paperbacks, and the influence of psychedelics and surrealist painters such as Dalí became more apparent. Artists like Richard Powers created semi-abstract dreamscapes for literary sci-fi such as J.G. Ballard and Ursula K. Le Guin, while Chris Foss painted beautiful candy-coloured spaceships and Bruce Pennington veered into the depths of darkness in some of his work.

Their art helped to shape reader expectations of the stories they illustrated, including Dune by Frank Herbert and the novels of Ray Bradbury and Isaac Asimov.

Around the same time, French artists such as Moebius (Jean Giraud) and Philippe Druillet were pushing the bande dessinée tradition beyond previous limits with their extraordinary visions, expressed in comic form in the magazine Métal Hurlant. Heavy Metal, the American version, would go on to bring that aesthetic to wider audiences.

Moebius would later work on films such as Alien and The Fifth Element, and both artists have had a huge influence on the speculative artists who’ve followed them.

The influence of cinema

Cinema has been both a huge influence on sci-fi art and a generator of it. Kubrick’s 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey employed space artists including Bonestell to ensure a sense of realism, and had a massive impact. Ralph McQuarrie’s iconic work on Star Wars helped to define a universe which is still hugely successful today.

By the 1980s, concept art for films was leaning more towards gritty cyberpunk, with an aesthetic that was usually urban, decaying and awash with technology, often in neon colours. Syd Mead’s work on Blade Runner is the obvious prime example, and was a huge influence on book cover design during this period.

Around the same time, H.R. Giger became prominent for his work on the 1979 film Alien, and Japanese sci-fi art – especially manga and anime – became a global influence, largely through works such as Akira, Ghost In The Shell, and Nausicaä.

Russian sci-fi art, long used by the Soviet regime as a form of political propaganda, began to move into new territory after the fall of the USSR, exploring more individual visions of the future and drawing inspiration from Russian culture and history.

Film concept art became more than just a tool for pitching specific scenes and instead became a way to create entire universes. This approach extended into gaming in the decades that followed as games became more complex, with titles such as Halo, Mass Effect and Destiny owing as much to their designers and concept artists as to their coders and writers.

A global digital future

The rise of digital capability is the biggest shift that sci-fi art has yet seen. Bonestell used to make miniature models of his subjects, such as lunar terrain, before lighting them as accurately as possible and photographing them. He would then project the photos onto his canvas to use as a compositional base.

This astonishing level of accuracy and attention to detail can now be achieved in various digital ways, with tools like Photoshop, 3D modelling and rendering, and of course more recently also AI.

This is perhaps the most exciting moment yet in the history of sci-fi art

Speculative artists have more tools than ever at their disposal as well as the means to find each other more easily. This has both democratised and globalised sci-fi art: there are various online communities dedicated to it, where any artist can share their visions of the future.

Movements such as Afrofuturism are offering new visions, inspired not by narratives of empire but by reimagined histories and stories from the diaspora. Sinofuturism is preoccupied with what China might look like in years to come, with artists such as Lawrence Lek and Xin Liu exploring issues around technology, politics and autonomy.

In Russia, a new generation of sci-fi artists are using speculative art to explore Russian culture in unexpected ways: the work of Anton Frolov, for example, blends traditional Orthodox iconography with sci-fi imagery into works which look both familiar and strange.

In Europe, Swedish artist Simon Stålenhag fuses nostalgia with sci-fi creations – vast mechanistic creatures placed in pastoral Sweden – while Arab artists such as Sophia Al-Maria and Sara Sadik, while not yet coalesced into a single movement, are exploring something that might yet become Arabfuturism.

This is perhaps the most exciting moment yet in the history of sci-fi art. With new technologies at their fingertips and global platforms for sharing their work, artists from a wide range of cultures and traditions are expanding the genre in bold and unexpected directions.

The future they imagine isn’t dominated by one voice or vision – and the result is richer, stranger, and more provocative than ever.

But sci-fi art has never just been about shiny rockets or lurid covers. At its best, it invites us to dream – not just about other planets, but about other ways of being. As technology continues to reshape every part of our lives, this kind of visual speculation becomes more important, not less.

Sci-fi art helps us question what we want from the future, what we fear, and what we might still hope for.

Like all art, it reflects who we are. But uniquely, sci-fi art also asks who we might become. It can explore the depths of the human experience and it can show us what’s possible. And of course, it can be fun too.

Image credits: Frank R. Paul, and also Frank R. Paul