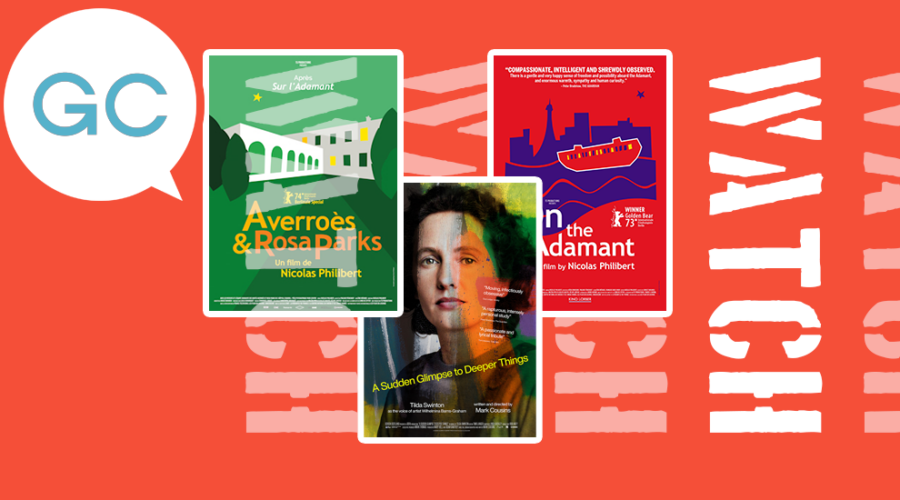

“Rubik’s Cube meets Rothko” is how Mark Cousins describes the style of Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912-2004), “one of the foremost abstract British artists” (per Wikipedia), though certainly not a household name. It’s an oversight the unconventional documentarian is determined to correct with 2024’s A Sudden Glimpse to Deeper Things. (And enthusiastically so. A rhapsodic monologue about one particular painting ends with the cinephile behind the 15-hour The Story of Film: An Odyssey proclaiming, “David Lynch would love this.”)

Indeed, Barns-Graham was and is a formidable character, a woman in an artists boys’ club who saw the world quite differently – literally – than those around her.

An adventurous globetrotter, Willy (a nickname that helpfully fooled collectors into assuming her work was crafted by a man, and thus worth collecting) possessed the gift of synesthesia, which allowed the prolific talent to transform letters into colors, and to perceive life as a series of structures and grids.

In fact, it’s this way of seeing, and the juxtaposition of the mind of the artist with her artwork, that ultimately fascinates the filmmaker/narrator (with a little VO help from Tilda Swinton). And because the Scottish-Irish director’s passion bordering on obsession is always endearingly contagious, us as well.

At the other end of the spectrum is Nicolas Philibert’s languid long-form trilogy, 2023’s On the Adamant and 2024’s Averroès & Rosa Parks and The Typewriter and Other Headaches.

Forever cinematically riveting, and providing unexpected revelations from frame to frame, the works simultaneously function as master classes in humanity.

All three feature an endlessly fascinating group of neurodivergent adults and their caregivers, close-knit and overlapping communities that have formed at the Adamant, a floating day care center on the Seine, and at Averroès and Rosa Parks, two sections of the affiliated Hôpital Esquirol.

More than a collective portrait of compassion, though it’s certainly that, it’s one of respect. A lesson in deeply looking at, and actively listening to, fellow human beings whose thoughts and fears, dreams and delusions may be far different from your own; but who nevertheless have the ability to upend some preconceived notions you perhaps weren’t even aware of, and in the process teach you something life-changing about yourself.

In other words, like all of Philibert’s majestic nonfiction dramas (2002’s To Be and to Have, 1992’s In the Land of the Deaf), they expand our filtered worlds.