As I write, law enforcement are descending upon Smyrna, Delaware, attempting to put a stop to a hostage situation at Vaughn Correctional Center, with prisoners holding guards and making demands for reform. One of the reasons they opted to move now, they say, is fear of Donald Trump — the scant progress made in the direction of prison reform under President Barack Obama may be about to roll back. The administration has already made it clear that it doesn’t respect the rule of law, the Constitution, and the U.S. Code, rewriting the law where it sees fit to accommodate nepotism, graft, and greed. That’s not a good sign for marginalised communities, as prisoners know full well; they are acutely familiar with what happens when the government turns its back on its people.

Over 2.3 million people are incarcerated in jails and prisons across the United States. Some have been convicted of crimes. Others haven’t. Some are residing in privatised, for-profit facilities. Others are in publicly-funded institutions. Some are trapped in solitary confinement. Some are immigrants who may wait months or years for hearings, deprived of due process due to their residency status.

The massive prison-industrial complex in the United States is heavily racialised. People of colour, particularly young men of colour, especially Black men, make up a heavy proportion of the prison population. Prisons are in some sense a natural extension of systems of slavery and Jim Crow — the criminalisation of bodies of colour is an ancient tradition that predates the United States itself. The school-to-prison pipeline preys on youth of colour, racial bias in policing and jurisprudence profiles suspects of colour, racist juries convict them, and the cycle feeds itself.

Once in prison, people are subjected to horrific conditions, despite the existence of standards that are supposed to set guidelines for the treatment of prisoners. They receive substandard health care — especially mental health care, and the prison system is the largest provider of mental health services in America. Some states have had such terrible health care systems that third party receivers have stepped in to take control, as in California. The food is often atrocious in addition to being insufficient for nutritional needs. Promised access to educational resources is denied. Rape and physical assaults are a persistent fact of life. Many prisons are severely overcrowded, leading to issues like bathrooms overflowing with sewage and limited yard time.

Many prison systems also use their inmates in forced labour, for which they are paid a pittance — inmates fight fires, perform construction for the state, and engage in other grueling activities. They’re also ‘leased’ to private companies in for-profit arrangements.

While the Angola Prison Riot may be famous, it’s far from the only time prisoners have coordinated, against the odds, and risen in resistance to oppression. Often, such coordination is extremely challenging, as prisoners cannot freely pass news and information between each other in the same facility, let alone across the prison system. Yet, they’ve done it, repeatedly, sometimes from solitary, as in the case of a hunger strike at California’s brutal Pelican Bay. Across the country, prisoners have repeatedly risen in protest, whether passively or actively, from hunger strikes to situations like that unfolding in Delaware. The #VaughnRebellion could be the next chapter in prison history, and it’s not the first time prisoners have put their lives on the line in search of justice while those who live free stand by.

The prisoners are demanding pretty basic things. They want access to an education. They want an actual rehabilitation program that provides them with valuable, useful skills. They want accounting transparency, to see how much money is being spent and where it is going.

These are simple, consistent things, along with basic improvements to living conditions, themes that emerge again and again in prisoner actions.

But it is not just prisoners who are in open rebellion.

Earlier this month, a sit-in at the office of Alabama Senator Jeff Sessions resulted in six arrests, including the president of the NAACP. They didn’t just call their senators about Sessions’ nomination to the Department of Justice: They stormed his office in resistance. These bold Black activists know the cost of failing to intervene even if their actions meant going to jail.

On Saturday night, taxi drivers in New York City refused to service John F. Kennedy Airport between the peak hours of six and seven. They were striking in solidarity with those affected by Trump’s ban on immigration from a number of majority-Muslim countries. For some, this is personal: Immigrants made up 90 percent of the taxi workforce in 2004. Whatever the specifics of their immigration status, they know what it’s like to travel to the U.S. in search of opportunities, and they know what it’s like to experience systemic racism.

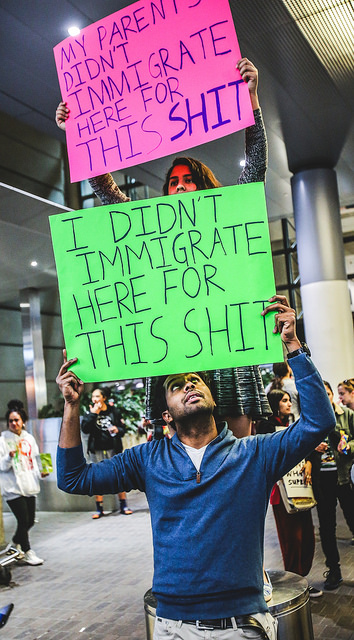

Tomorrow, over 1,000 bodega owners across New York City had pledged to go on strike — as with taxis, the workforce at bodegas draws heavily on immigrant populations, including those targeted by Trump’s executive order. Those seeking a quick snack at the corner store — or wanting to pet the resident bodega cat — are in for a rude awakening between 12-8 tomorrow. In some senses, their action is a reminder of the Day Without An Immigrant protest in 2006, in which immigrants across the U.S. walked off the job to protest xenophobic immigration policy.

These protests are striking, and vital, because of their organic nature. They were organised quickly and spread like wildfire because of the collaborative communities that backed them. Marginalised people understand the need to band together to defeat oppression in what Black Lives Matter refers to as a ‘leader-ful movement.’ This isn’t about orientating and organising around a core figure, but about rising together in solidarity.

This strike will likely be brutally put down, particularly as a guard was injured during the takeover. American law enforcement have a long history of using injuries and deaths among law enforcement as a justification for violent takedowns. But it’s not going to be the only prison strike to rise and resist Trump.

It’s notable that those with the most to lose are among those who are first to put their bodies on the line. The stakes for prisoners involved in strikes, especially those profiled as leaders, are huge. Their ‘privileges,’ like fresh air and sufficient food, may be rescinded, and they could be sent to solitary as punishment. It’s possible that time will be added to their sentences, particularly in the case of those who can be prosecuted for assaulting the guard. Similarly, immigrants engaged in resistance action risk deportation even if they have complied with every last detail of immigration policy and have papers perfectly in order.

For them, this is personal — they risk everything because they have everything to lose. Americans in more protected classes have to decide whether they want to participate in that resistance, or stymie it. Those who descended on airports across the country over the weekend sent a clear signal that they were prepared to act as human shields for immigrants and refugees. Those who punch Nazis in the face are firmly declaring where their allegiances lie, that the time for polite debate and conversation has passed. But those calling for civility and ‘being the better person’ have also established their credentials, as have those who have clambered over protesters, crossed pickets.

People have asked: ‘What would I have done in 1930s Germany?’ Well, it’s here, and they’re about to find out, because it doesn’t take much of a resistance to topple a dictator, but it has to be a sustained, coordinated resistance. Over one percent of the U.S. population turned out to march on 21 January — can Americans drive that into a resistance to tyranny not seen in the U.S. since the late 1700s?

Photo: Cindy Chu/Creative Commons