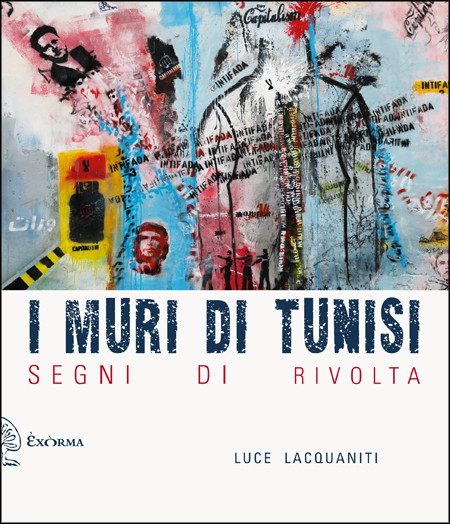

“The first sign of the 2010/2011 revolution was the graffiti on the capital’s walls, really. For those who knew Tunis before the revolution, it seemed like the city filled with words almost overnight” says Italian researcher Luce Lacquaniti, author of the book The Walls of Tunis: Signs of Revolt, published in Italy by Exorma.

She explains that before the revolution, the walls were completely blank:

She explains that before the revolution, the walls were completely blank:

“It wasn’t just the government that was erasing the writing from the city walls. It was also the citizens, who deemed writing revolutionary statements on the walls pointless if nothing ever changed. But when the revolution started, suddenly everybody wanted to have a say in politics”.

Whereas in other countries graffiti is mostly decorative, 99% of Tunisia’s is political. In her book, Luce uses the writings as a key to understanding the period of transition in Tunisia – from the 2011 revolution to the elections in 2014 – pointing out transformations and contradictions.

After studying Arabic and travelling the Middle East, Luce made Tunis her second home. In the beginning, she photographed the graffiti as simply a personal record, driven by her long-time interest in street art. On returning to Italy, however, she realized that foreign media had a very partial view of the events unfolding in Tunisia.

“It was very difficult to understand what was going on in Tunisia from abroad. I thought that the writings could give an outsider a more precise picture of the everyday reality – what people in the streets and in the cafes were thinking as opposed to the ‘official truth’.”

For her, the graffiti is comparable to historical documentation.

Luce started revisiting Tunis regularly. By then she already had the book in mind and an agreement with an Italian publisher. She repeatedly went back to the same spots to see how the writing had changed.

“La Ville Nouvelle, the city centre, is where the writing is mostly concentrated. Other places are the Trabelsi family villas, the government headquarters and the Kasbah.” At the same time, some graffiti crews decided to work in the suburbs: “I see that as a reaffirmation of the outskirts, which have always been overlooked. Thanks to the graffiti they have become places for poetry and freedom of expression.”

A section of wall in Avenue Bourguiba, called Les Arcades, was one of the spots Luce came to photograph on several occasions: “Through the writing on these walled arches you could really observe all the phases of the revolution unfolding – from initial enthusiasm, to doubt, then to disputes, disillusion and eventually the total stagnation of the debate.”

The first writing on Les Arcades dates back to the first months of 2011: “How beautiful Tunisia is without Ben Ali Baba and the 40 thieves!” (an allusion to the Trabelsi family, the relatives of ex-president Ben Ali’s wife). In the following months, the graffiti was erased and a new slogan appeared: “Freedom is a daily practice”.

A picture from 2012 shows three different messages overlapping, mirroring the three souls of the country. The first, in black paint, remains enthusiastic: “Long live Tunisia, free and democratic!” The red paint of the second is contradictory: “The revolutionaries say: you can’t fool us”. The third one is written in pencil: “There’s no god but God and Muhammad is His Prophet”.

At this point, the provisory government elections had been won by the Islamist party Ennahda. Their presence is also affirmed in graffiti.

“One would think that conservatives don’t write on walls, that it’s just young radicals who do so,” points out Luce. “On the contrary, writing is a phenomenon that has involved the entire society.”

This is because the walls are open and accessible to everyone. In that sense, walls have been far more democratic in spreading the revolution than the much-lauded internet: “It’s not the case that in Tunisia everybody owns a computer and knows how to use it. This holds especially true in the rural areas, which is precisely where the revolution started”.

The issues discussed on the walls are the nature of revolution, forms of repression, the relationship between religion and politics, and problems involving gender. According to Luce, the writings are an integral part of the debate taking place in assemblies, newspapers, shops, and private homes.

While everyone participates, in her book Luce identifies three major militant graffiti crews, whose members are all in their 20s and 30s.

“One group is called Zwewla, which translates as “the poor”. Their choices are tied to the concept that the revolution didn’t stem from politics or a desire to bring down the regime. It requested social justice first and foremost. For Zwewla, it’s not about secularists, Islamists or politics. It’s about the redistribution of wealth, more employment and economic growth – especially in the more marginal regions of Tunisia.”

Zwewla’s members are themselves from poor areas and lives of hardship. “That’s why they encourage everybody from a similar background to sign their comment with the name Zwewla. You don’t need an official subscription to the group to use their name. That’s part of their idea of social inclusion.”

Another group, called the Molotov, gives a literary twist to their writing. “They express political concepts by quoting poems and making philosophical parallels. They are on a mass acculturation mission” explains Luce. “That’s why for their writing they always pick the outskirts and neglected areas. Their intent is educative and didactic, always tied to current politics and events.”

A third group is called Ahl al-Kahf and formed at the art academy. Formally, they are much closer to street art. They have even written a manifesto in which they declare their art is universal, atemporal, and extendable to everyone who wants to join in.

“They have studied art theory and the French philosophy, from Michel Foucault and Deleuze to the Situationists, and they reference Mahmoud Darwish’s poems. Nonetheless, their aim is also to be inclusive.”

In a similar way to Zwewla, Ahl al-Kahf also invites people to grab a spray can and sign an Ahl al-Kahf piece with their name. “Because the work of art value is determined by its signature”, they say, implicitly criticizing the art market.

They too quote writers and philosophers from both Arabic and Western culture. Unlike the Molotov though, which are all about plain writing and the message, Ahl al-Kahf also creates portraits.

In 2012, two members of Zwewla were arrested for writing on the wall of the University of Gabès. They were accused of “spreading false news to disturb public order”. Thanks to the intervention of Amnesty International and other NGOs, they got away with a hefty fine.

Luce’s book concludes with the elections in 2014. Even though there is still a lot to achieve in terms of freedom of expression, Luce feels that things have improved since the revolution.

“At least now when something like that happens, society reacts and the associations take action. In the past, inconvenient people just disappeared.”

Luce’s research in the urban and artistic scene of Tunis doesn’t end with her book. She has recently opened a cultural space in Rome, her hometown, called Kif Kif, hosting concerts, art shows, and presentations, and allowing culture from Tunis, the MENA region, and beyond to come into contact.

Image credits: Luce Lacquaniti