Kyiv’s Gogolfest has both grown and remained distinctly itself – not the easiest feat to pull off. Combining theater, music, visual art and workshops, the festival is the brainchild of Vlad Troitsky, the man behind the Dakh Center of Contemporary Art, a tiny theater near Lybidska metro station in Kyiv that has already achieved legendary status among those in the know.

In Ukraine, theater is regarded as genteel and boring – something for dainty virgins to enjoy when they’re not crocheting. By contrast, Troitsky is not afraid to be jarring both visually and emotionally. The work he does as director and organizer is organic to the chaos at hand in Ukraine, and local and international audiences have been responding strongly to everything from his weird, mystical takes on Shakespeare to his own biting commentary on modern times.

After the close of this year’s Gogolfest, I had an opportunity to speak to Troitsky about Ukraine, modern theater, politics, travel visas, people who drink beer at 9 a.m., and what potentially awaits us after the 2010 presidential elections.

Natalia: Now that the festival is over, can you comment on how it went this year?

Vlad: That should really be up to others. Personally speaking, I think it went well. I think the public’s reaction was good. We’re trying to organize an entirely new mainstream, something free of flag-waving and knee-jerk patriotism, and I think we’re succeeding. Attending the festival, people have a chance to not feel provincial next to Russia, next to other European countries.

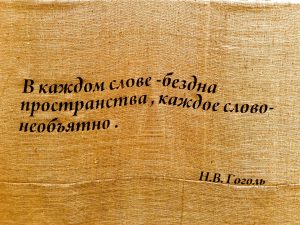

Natalia: You’ve said before that the reason why the festival is named after Nikolai Gogol has to do with the fact that Gogol is the one Ukrainian cultural figure who is very much European. What do you mean by that?

Vlad: Gogol is part of a great humanist tradition in Europe. He was a rare individual. Even today, you look at our modern immigrants, people who go abroad and supposedly engage with the rest of the world, and you see how they viciously criticize the place they left and the place they moved to. Gogol had none of this typical small-mindedness. That appeals to me.

Natalia: Speaking of small-mindedness, you’ve had a lot of harsh words for the way that Ukrainian art and culture are maintained, or not maintained. Do you think things might change after the 2010 elections?

Vlad: I don’t know. The problem with our country is that there is no strategic thinking where the arts are concerned. Government is like a revolving door, people don’t even have time to make sustained efforts, because they come and they go. In that sense, this is why Gogolfest is such a feat – it’s so hard to secure any kind of meaningful support for it. But it keeps happening.

Natalia: Your rhetoric around Gogolfest is interesting. You’ve spoken of the festival as a kind of ‘cultural mall’ and a distinct ‘brand.’ Looking at our cultural landscape, I wonder if established people…

Vlad: Established? There’s really no such thing as “established” figures around here. Everyone is marginalized, with the possible exception of [actor] Bogdan Stupka.

Natalia: I guess what I’m trying to ask is this: among our cultural gatekeepers, do you get criticized for using business-oriented language?

Vlad: You get criticized if you do anything. If you do nothing, then great, everyone leaves you alone. But it’s not that I necessarily like translating culture into business. Above everything else, the festival is an opportunity for people to feel like human beings. That’s the main point of it.

Natalia: I want to return to what you just said about marginalization. I remember you once commented that in richer nations, wealthier people can cut themselves off from the marginalized, they don’t have to deal with them every day, which isn’t really the case in Ukraine. Can you expand more on that?

Vlad: What does the word “marginalized” mean, anyway? Look at it in context. In Ukraine, the boys and girls who are getting drunk on the sidewalk in the morning, they’re not the marginalized ones. To be marginalized is to not be needed. The people clutching their beers at 9 a.m., they’re needed. In this country, it’s kids who, for example, attend music school who don’t matter to anyone. They’re the real marginalized group. Anyone with an iota of talent dreams of leaving, because nobody cares about them and their work.

And the top of the social hierarchy in Ukraine doesn’t deal with reality either. They don’t have to. There are a lot of rich people in Ukraine these days, the leaders of society, and you just have to wonder if they’re intelligent at all. That’s the real question.

Natalia: I’ve noticed you’ve had a lot of warm words to say about England and English society.

Vlad: I have a lot of warm words to say about Germany, about France. I like England a lot, though, because it’s able to remain so distinctly English.

Natalia: Plenty of English people would not agree with you on that. Everyone seems to talk about how England today is irrevocably changed.

Vlad: Well, that’s the way of all cultures, isn’t? I still think that English culture in particular is holding out as something very distinct, even as people of different backgrounds join it.

You know, I’m a tourist in London. I don’t know if I could get used to living in such a megapolis. Kyiv, by comparison, is something else entirely. Speaking of travel, did you know that the Dakh company and I were supposed to go to the U.S. recently for a private performance, and weren’t able to get a visa?

Natalia: That is the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever heard.

Vlad: It’s the reality of how Ukraine is viewed by U.S. officials. We’re on a certain tier at the moment.

Natalia: That’s infuriating.

Vlad: It is what it is.

Natalia: As far as differences between Ukraine and Western nations go, you’ve said that Western theater as very much its own thing, something that contrasts sharply with local theater. Can we talk about that?

Vlad: Well, which Western theater are you talking about? Are we discussing Edinburgh? Avignon? I think the main difference is, Western governments care about high art and know that it must be protected. High art is elevated to prestigious status. Look at all the people clamoring to make it to the Fringe, or to get good tickets to a famous opera house. We don’t have that in Ukraine.

Consider the fact that not a single presidential candidate even attended Gogolfest. What does that tell you? I don’t know if they’re afraid, or if it’s something else, but it sends a particular message.

Natalia: That’s such a contrast with Russia, isn’t it?

Vlad: Russians are raised to love their high art and to believe in it. It is its own unique phenomenon. Most of it is does not engage world culture, with notable exceptions, such as the work of Andrei Zvyagintsev, Alexander Sokurov, Alexei German and others.

Natalia: Not Nikita Mikhalkov?

Vlad: I think Mikhalkov has lost the plot.

Natalia: Tell me about all of those big Hollywood stars you admire.

Vlad: I admire hard-working people: Leonardo Dicaprio, Nicole Kidman, Brad Pitt. They have a work ethic that’s largely missing in Ukraine today.

Natalia: And why do you think that is?

Vlad: Look at it in context of breaking away from great Russian theater and standing on our own. We are independent, great, but we’re not cultivating ourselves. When we do cultivate ourselves, it’s mostly done on a very local level, as opposed to national level. Kids who study theater and acting have no myths to propel them forward. Their highest ambition? Get on some middling TV show. Right now, this is the highest career peak they can dream of.

Natalia: Seems like that’s changing already. Though there’s always that temptation to be sad after a festival, no? When everything has been taken apart, and you have to wait until next year?

Vlad: It’s part of the art. After people witness the ending, the dismantling, the sense of sadness that accompanies it becomes another experience to take away with them.