Like many people, I came to politics—and writing about politics–through music. I discovered punk rock, and it led me to different ways of thinking about the world. Music has always been a way to keep alive the stories of people and places, creating a rich, living history that textbooks can never match.

Antonino D’Ambrosio, like me, discovered Johnny Cash after a lifetime of punk rock, and in his new book, A Heartbeat and a Guitar: Johnny Cash and the Making of Bitter Tears, he weaves together the threads of American folk music and popular song, street protest and social justice movements, and the painful history of American colonialism into one compelling tale: a story of one man’s journey but also of all the people who literally or by taking part in that history contributed to the making of an amazing protest record.

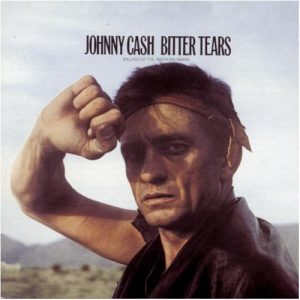

Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian wasn’t one of Johnny Cash’s best-known records, but D’Ambrosio chose to tell its story because it showed a side of Cash that most people don’t know. He spoke to Sarah Jaffe about the book, Cash, and the impact of music on American political consciousness.

Sarah Jaffe: Can you tell us how you started to think about writing about music and politics together?

Antonino D’Ambrosio: For me, music was the point of entry to seeing the world in a much broader way. Music early on, particularly the Clash, showed me that the world was this wonderful place and we were all interconnected, interdependent. It really challenged my narrow view of things, when I was only 12 years old. It’s something that I’ve seriously held on to throughout the rest of my life, something that inspired and motivated me to engage in a way that is not sometimes so heavy and hard.

Music is fun and exciting, and it helped me realize that some of the most important issues of the day are in the music that you’re listening to. Certainly in punk, but also Johnny Cash, who I came to later when he was doing his American Recordings. It was a transformative experience for me and underscored how important music is. There’s this prophetic, timeless quality to Cash. It touches your soul.

I’d never really paid attention to folk music or traditional music. It was another experience for me, how amazingly talented storytellers all these musicians were, Pete Seeger, Dylan, of course Cash, and Peter La Farge, the guy that wrote “The Ballad of Ira Hayes.” It’s a very powerful thing that you can tell a story like the Ira Hayes story, this tragic tale, a metaphor of the United States’ injustice toward Native people, and tell a story in 3 minutes and 41 seconds that has all that history packed into it. All of that came together. There’s a lot of power in art, trying to achieve telling the truth and music I think is the best at it.

SJ: This book ties together so many threads, so many social movements, that people might not think about being connected.

AD:That’s a big thing for me in terms of my work. That’s something that I did with the Clash book and I do with my films as well, really challenge the calcified bits, stereotypes of how you perceive things, the one-dimensional approach. It’s a trick to keep us separated as people. On a social-political level, it’s very effective to make you think you’re independent, not connected to each other, but that’s not true at all. In my work I try to create a framework. The Cash book itself, that’s just a frame to build a house to tell that story of that time in America.

It certainly points to the future, too. The album is framed around five different narrative threads, around human rights and particularly Native rights, but the issues that it’s talking about are still very much present today. Whether it be what’s happening in Iraq or the myriad wars that are going on in the world, or specifically, the issue of Native peoples are still pretty dire.

SJ: The sixties were this time period where all these social movements were taking place and it seems that the only one that really doesn’t play into this book is the feminist movement. We all know about Johnny and June Carter, but what role did she play during the making of this album?

AD: I stopped at ’64, and a lot, not just the feminist movement, but the anti-war movement was just getting started. But June Carter was fundamental in a way that the movie [Walk the Line] missed, I think. Obviously I didn’t have the space I wanted to to talk about it.

Johnny Cash wasn’t the best musician or best singer, but he had this unique vision and he had a force of good about him that could rise above everyone else and become one of this handful of the modern era’s great artists. But June Carter was amazingly talented in every way. She was a great musician, a great singer, a great entertainer, and in many ways she was a great complement and also a great mentor to Cash. She was part of the Carter family, and one thing I discovered in working on the book was that there was probably no other group in the history of American music that has had such a profound influence on American music as the Carter family. Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, to the Clash and Public Enemy, it’s that diverse.

On the album Bitter Tears, Peter La Farge’s songs are very sparse, very stripped down, and for Johnny Cash it was new, playing with some new sounds, some traditional sounds. But they used June Carter’s voice on like every song. It gives it this emotional weight, this beauty that takes the songs–the sadness and the power–it really takes the struggle to a more profound place. It’s something I always notice every time I listen to the record—I’m having musicians perform with me in every city I go to, and one trick for me is to find the June Carter aspect in doing that, because every time I listen to the record her voice just shines.

SJ: Since we mentioned the movie—we just saw this big Johnny Cash biopic and yet your book tells this whole different story. It really speaks to how many stories there are in somebody’s life.

SJ: Since we mentioned the movie—we just saw this big Johnny Cash biopic and yet your book tells this whole different story. It really speaks to how many stories there are in somebody’s life.

AD: Part of my work is trying to use popular culture to tell people’s stories in a way that allows people to connect with them, they become valuable to their lives. Walk the Line is not a bad film at all, but the coverage of the time period that I wrote about in the book is just nonexistant. And of course there’s things that they need to put together or cut out for dramatic effect.

The mystique of Johnny Cash is the myth of this man in black, the rebel outlaw, but it really detracts from his truer self, which I think Bitter Tears was—I think that’s the truer Johnny Cash. Making this record, the year after he had his biggest hit, right after the Walk the Line album, was a very courageous thing to do. It was like adding another plaintiff to the case against American injustice. With all the social upheaval of the time, it was the last thing anyone wanted to hear.

SJ: Along those lines, the movie really dealt with this classical addiction narrative, but he made this album while he was doing these handfuls of amphetamines at a time. It really complicates this narrative that we’re used to, that he made this amazing album while he was a complete mess.

AD: I think that he was a person in pain. The agony that he felt in his life never left him. The movie makes it seem like he kicked drugs, which never happened. He had moments that lasted a month or two, but Marshall Grant, the bass player from the Tennessee Two, who told me that he never kicked them. That’s also a disservice.

The fact that he did this while he was dealing with his own personal agony, and that was being reflected back in the work about the tormented Native people–I think you can’t have one without the other. I think that’s an important thing, because the sincerity, the authenticity that Johnny Cash had, in all his music but particularly Bitter Tears, is very important. It separates a great artist from an average musician.

SJ: Speaking of that sincerity, you mentioned once when he performed these songs for a Native audience, you mentioned people not really knowing what to make of “Ira Hayes.” Did he ever experience pushback, that people thought he was appropriating Native issues?

AD: It’s funny, I was saying last night about “I Walk the Line,” the line that he really walked wasn’t about love or anything, it was this really fine line between being a person who had concern for others and the human condition, and a desire to be an accepted artist. In my research, all the Native activists that I talked to, everyone had such reverence for him. These were people who weren’t necessarily into his work, but I didn’t encounter [the question of appropriation] from anyone that I talked to.

I think the stuff that he did get flak for was the same thing that Peter La Farge got flak for with “Ira Hayes”—they think that they’re putting down Ira Hayes as a drunk, and the stereotype of the drunken Indian is something that Natives obviously detest. That’s really the biggest thing that I encountered, confusion when people heard that song. As I say in the book, Marshall Grant tells me, they just never stopped playing it.

Cash had a moment—there were times where he did appropriate the image of a Native person, saying that he was part Cherokee and all. Years later he admitted that he wasn’t Native but that the album was a sincere call for support. But you could even argue—I don’t know if this record could even get made now, because he had such trouble getting it made then, when it was the thing to do, to write these finger-pointing songs.

SJ: You’ve written this book about Johnny Cash and the book about Joe Strummer, but is there anybody right now who has an interesting message, who is doing interesting political music?

AD: If we’re talking about the level of the Clash or Johnny Cash, it’s hard for me to find, even the Public Enemy’s of the world. There are these musicians like Ted Leo or Radio 4, who are well known but not at the level of a Johnny Cash; that really infects the popular culture, these people who burn to change things. Not to say that they don’t contribute to that, they do, but everyone has to play a role. At that level, I’m really hard pressed.

It’s something that frustrates me. I’ve encountered a lot of musicians who really shy away from politics and that’s even more of a political act than making an entire album of Native songs. In your belief that you’re not being political, you’re actually siding with the dominant ideology.

It’s frustrating to see that. It’s like a missed opportunity.

SJ: Around 2004, when we kind of saw all this music against Bush, all these rock albums and songs—even the Rolling Stones wrote a song against Bush and Cheney. And this year, this election we didn’t see things like that with musicians. We had this art involvement—Shepard Fairey, who did the cover for your book, did that famous Obama poster, but the musical involvement was gone.

SJ: Around 2004, when we kind of saw all this music against Bush, all these rock albums and songs—even the Rolling Stones wrote a song against Bush and Cheney. And this year, this election we didn’t see things like that with musicians. We had this art involvement—Shepard Fairey, who did the cover for your book, did that famous Obama poster, but the musical involvement was gone.

AD: I think that a lot of people were frightened. We had reached a point of desperation in this country, where a candidate like Barack Obama–he might be the smartest president we’ve had in decades, and he’s probably the most decent person we’ve had in like a century, but he’s not a radical or really progressive candidate. I’m pretty good friends with Chuck D and he wasn’t really a supporter of Obama. He wanted someone to be more strident, to push for the change that really needed to happen.

Artists have always been tentative in America. Art in general is not appreciated here. There’s a feeling that if you pursue art, you’re not really working, you’re not contributing to the economic elements of America. Anything that doesn’t work for or promote that, they’re not going to support. We have the most underfunded arts in the industrialized world.

When you take that all together, we don’t really have large popular culture based artists like that anyway, and then you’re at a point where this guy HAS to win. If he doesn’t win–we’re already drowning. We’ll never get to the surface. I think people were really reluctant—I think that’s why Shepard decided to do a poster that was super positive, “Hope,” because it was like we had to get back to ground zero, to turn the corner.

In many ways it’s anti-democratic. Democracy has to run on criticism, you have to be critically thinking about where you want to be every moment so that the sinister forces don’t rise up and overwhelm. It’s one thing that we’ve experienced in this new millennium, under Bush.

It’s a frustrating thing; back to an album like Bitter Tears. Native activists told me that Obama had already done more for Native people than anyone ever had and he’s hired three people. And he’s got a Native policy czar. That’s actually very cool, but that’s something that shouldn’t have happened in 2008, that should’ve happened years ago.

One thought on ““A Heartbeat and a Guitar”: Antonino D’Ambrosio on Johnny Cash”

Comments are closed.