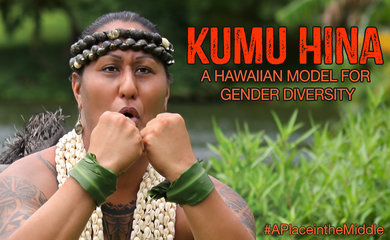

Mark your calendars and set your DVRs. If orange is the new black, then Hawaii is the new cool state. Premiering Monday, May 4th on PBS’s Independent Lens is Kumu Hina, Dean Hamer and Joe Wilson’s uplifting portrait of gender and cultural empowerment in the Pacific. This enthralling documentary follows titular subject Kumu (“Teacher”) Hina Wong-Kalu, a married woman and dedicated cultural mentor at a native Hawaiian school who also happens to be māhū – or what the west would call a transgender person. As we watch Hina ready her all-male hula troop (which includes one kickass sixth-grader, born female but an out-and-proud māhū) for their year-end performance, and struggle in her relationship with a heterosexual, cisgender Tongan man, what emerges is something extraordinary. Through their patient, cinema vérité style, Hamer and Wilson give us a glimpse into a world where aloha – “love, honor and respect for all” – is not just a catchy word or an abstract idea, but truly a way of life.

I was fortunate enough to speak with the award-winning co-directors prior to the doc’s public broadcasting debut (programmed in celebration of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month).

Lauren Wissot: Can you discuss the origins of your latest doc? How did you meet your subject Hina Wong-Kalu in the first place?

Dean Hamer and Joe Wilson: We spent 2005-2009 producing and then conducting an extensive grassroots community engagement tour with our first PBS documentary, Out in the Silence, which focuses on the discrimination and brutality faced by a teenager who came out as gay at his small town high school in Pennsylvania. Everywhere we went, we heard similar stories of the difficulties faced by LGBT youth, especially in rural and small town America.

Then in 2010, we visited Hawaii to present the first Out in the Silence Award for Youth Activism to the Gay Straight Alliance at Farrington High School, a large public school in inner city Honolulu. We arrived at the school to find a gymnasium full of 2,000 raucous students, mostly from Pacific Islander families, being led in cheers by an ebullient young person we immediately recognized as transgender: someone Hawaiians refer to as māhū, one who embodies both male and female spirit.

Unlike the typical narrative across the continental U.S., where openly transgender students face rejection, brutal bullying, and violence, this cheerleader was at the center of popularity in her school. We were stunned, and deeply curious about what made such reactions seem not just possible, but normal in Hawaii.

So when our Hawaiian friend Connie Florez, who became a co-producer on the project, told us that she was very close with a māhū woman who was a respected teacher and community activist, we were eager to meet her. That was how we first encountered Hina Wong-Kalu, known affectionately in the community as Kumu (or teacher) Hina, over dinner at a local diner. By the time we got to dessert, we knew we just had to make a film about this immensely regal yet down-to-earth woman, and the culture that surrounded and embraced her.

LW: The fact that native Hawaiian culture embraces māhū – those with male and female spirits – reminded me that Native Americans also have historically welcomed tribal members with dual souls. Indeed, transgender acceptance only went out the window when colonialism and western values conquered these folks. Yet I don’t recall, say, the American Indian Movement incorporating LGBT civil liberties into the larger context of Native cultural rights. Do Hawaiians truly view LGBT rights as a native Hawaiian issue?

DH & JW: The best way for Americans to look at such a question would be to try to step outside of their current frame of reference – where people identify as, or are put in, a particular categorical box aimed at describing who they are – and consider a Hawaiian view. In traditional Hawaiian culture, well before the emergence of LGBT in Western parlance, people who we might today call transgender or gay had a place and were treated with dignity and respect. Some were known as māhū, those who embody both male and female spirit, others as aikane, those involved in same-sex relations, often with chiefs, and a range of other Hawaiian words and concepts that respectfully denote more fluid ways of being in the world as relates to gender, sexuality, and relationships. Hawaiians didn’t have to consider whether or not such people’s rights were supported, because they were never denied in the first place.

In present-day Hawaii, however, a place deeply affected by Western religious and political colonization, there is no singular native Hawaiian view of LGBT rights because native Hawaiians are not a unified group with a monolithic political perspective any more than any other population demographic. They are diverse. Some Hawaiians have adopted conservative religious beliefs, some have not. Some Hawaiians are politically liberal or progressive, some are not. In this context, Hina and other young leaders have been very effective at applying a Hawaiian philosophical lens to issues of great concern in the contemporary political landscape.

In 2013, for example, when a special legislative session on marriage equality was roiling the state capitol and pitched partisan battles were taking place, mostly in a Western religious framework, Hina authored an op-ed on Hawaiian culture’s deep tradition of acceptance and inclusion that became a galvanizing way for a broad majority of people to support the bill. It was subsequently passed with little opposition, and Kumu Hina was invited to perform a special celebratory Hawaiian chant at the Governor’s Marriage Equality Bill signing ceremony.

Going forward, that is the goal of Hina’s work, and the emphasis of the educational work associated with the film: Offering viewers and the world stories that show a positive, Hawaiian view of gender diversity, inclusion, and empowerment that can be applied to a range of issues up for debate.

LW: Besides portraying a strong transgender woman unafraid to channel both her male and female sides – something we don’t see often enough in our gender binary focused society – you also delve into Hina’s love life, specifically her marriage to a “straight” Tongan man, Hema Kalu, that she met online. Honestly – and this is speaking as a genderqueer chick, a biologically female gay guy who knows firsthand the difficulties of getting involved with hetero dudes – that was the only aspect of the doc that made me squeamish. Perhaps I’m jaded, but I immediately thought, “Now there’s a relationship headed for disaster.” I just wondered if Hema wasn’t using Hina to gain U.S. citizenship, or at least get taken care of in some way. Did you have your own reservations about the relationship – and if so, did you express them to Hina?

DH & JW: You’re hitting on questions that a lot of viewers have shared, and that we ourselves, of course, had during the time that we were following Hina with our cameras. These are universal questions, applicable to most any relationship. But they’re a bit more heightened for Hina because, as she says in the film, it’s just more difficult for māhū to find someone courageous enough to be in a relationship in a society with prejudice. While there were times that we really worried about Hina and asked her about whether or not we should include some of the more sensitive scenes in the film, she said she wanted to bare the whole story, so people would see her reality, with hopes that it might help others in similar situations. For Hina, her strength comes from her sense of self as a Hawaiian, and she uses that strength and confidence that comes with knowing that your community supports you, as a way to persevere through difficult times. Today we’re happy to report that Hina and Hema are doing quite well. They even attend public screenings of the film to continue sharing aspects of their journey, both the ups and the downs.

LW: Dean, in addition to being an Emmy Award-winning documentarian, you’re also a prominent (New York Times Book of the Year) writer and NIH scientist, perhaps best known as the author of The Science of Desire and The God Gene. I’m wondering how your geneticist’s background influences your filmmaking, both in respect to choosing subject matter and also in how you approach your stories.

DH: What I learned as a scientist was always to look at the data first. Not the theory, not the way I thought things ought to be, not the way other people looked at the problem – just the observations. I approach filmmaking in the same way, which is why Joe and I strive to make true verite films that are driven by the characters’ actions and words. No outside narrators, no academic experts – just the characters.

Of course the other influence of my career in scientific research was our discovery of the important role of biology in sexual orientation – something long suspected but not preciously investigated at a molecular level. Those findings were clear evidence of the deep roots of human sexuality. Although gender identity has not yet been researched with the same rigor, it’s clear that people don’t “choose” to be transgender, any more than they choose to be cisgender. I hope stories like Kumu Hina will help people understand that being māhū, or in the middle, or wherever you are on the gender spectrum is perfectly natural.

LW: As filmmakers who’ve been exploring LGBT issues, both personally and professionally, over many years, I’m curious to hear whether you’ve seen an evolution not just in the newly same-sex-marriage accepting mainstream, but also in the homosexual community as a whole. I mean, it wasn’t too long ago that transgender people were marginalized not just by society at large, but by many gays and lesbians who couldn’t relate to having a body and soul mismatch.

DH & JW: For us the big question is not the evolution of the LGBT community but of all society. After all, the burden of fighting discrimination shouldn’t always be on the oppressed since they aren’t the ones causing the problem! That’s why both our films and our educational and outreach work are aimed at mainstream rather than niche audiences.

In the case of Kumu Hina, we’re currently focusing on a short version of the film, made especially for kids, called A Place in the Middle. Our hope is that this “true life Whale Rider story” will reach young people in schools all across the country and the world.