Last week, you could have been forgiven for thinking that the only political activity going on in the UK was #traingate. The most important story in the news was about whether a man sat down on a chair or on the floor of a busy train, a sign of the depths the Labour leadership campaigning has sunk to.

Meanwhile, in the real world, the government announced that it was going to go ahead with an attempt to scrap the Human Rights Act.

Liz Truss, the Justice Secretary, confirmed to BBC Radio 4 that, as a manifesto promise, the repeal of the Human Rights Act was a promise that Theresa May’s new government intends to uphold. The announcement, well hidden amongst left-wing infighting, was almost designed to go unnoticed.

The Human What Act?

The Human Rights Act was introduced in 1998 by Tony Blair’s Labour government and is designed to protect certain basic rights and freedoms. Including the right to life and the right not to be tortured, these principles protect anybody resident in the UK.

Based, essentially, on the European Convention on Human Rights, the UK’s Human Rights Act requires that British courts, as well as public bodies, adhere to its fundamental rights in the course of their work.

The fifteen rights enshrined in the law also include:

- Protection against slavery and forced labour

- The right to liberty and freedom

- The right to a fair trial and no punishment without law

- Respect for privacy and family life and the right to marry

- Freedom of thought, religion and belief

- The right to free speech and peaceful protest

- The right to live without discrimination

- The protection of property, the right to an education, and the right to free elections, protecting against state interference.

Now, I might be accused of being a bleeding heart liberal at this stage, but who doesn’t want the right to a fair trial and the right to free thought?

The Tories. They hate the link that the Human Rights Act gives us to the European Court of Human Rights, which has overturned UK courts on occasion when rights were not being adequately upheld. The populist argument against the Act is that it gives rights to criminals — especially foreign criminals (who are, for some reason, considered to be worse than native British ones).

The Human Rights Act could also be an obstacle in the way of getting Theresa May’s Investigatory Powers Bill passed through parliament. Known as the ‘Snoopers’ Charter’, the Investigatory Powers Bill promises unprecedented surveillance powers by security services.

The British Bill of Rights

The Conservatives’ plan, instead, is a British Bill of Rights, which would be based on British values (presumably the right to a decent cup of tea and complaints about the weather). The dreaded phrase ‘common sense’ has been brought up, as if respect for privacy or the right to live without discrimination are preposterous concepts that could benefit from a bit of straight talking. As many people are quoted as saying, ‘common sense ain’t common.’

Such common sense that Shami Chakrabarti, former director of civil liberties organisation Liberty, called the potential repeal of the Human Rights Act ‘the gravest threat to freedom in Britain since the Second World War.’

Bella Sankey, Liberty’s Policy Director, added:

Our country has seen a spike in hate and division in recent months. Just days ago, the Equality and Human Rights Commission laid bare the scale and challenge of racial inequality in Britain — and only today Transport Police have reported a leap in racist abuse and attacks. In the current climate, our new Justice Secretary should focus on providing unifying leadership – not pouring her energy, and yet more public money, into scrapping human rights and equality protections that are needed now more than ever.

While the threat to remove the Human Rights Act is certainly sinister, it is hard to know how dangerous it will be for UK residents, especially those who are vulnerable in some way (for example due to racism or disablism), without knowing what the British Bill of Rights would offer in its place. Charley Pattison, the Green Party spokesperson for Justice, told me that scrapping the Human Rights Act would water down the Government’s obligation to treat everyone with dignity and respect.

She said: ‘The Government has been talking about repealing the Human Rights Act since the General Election campaign in 2015, and they have intermittently alluded to introducing a British Bill of Rights in its place.

‘But they haven’t yet managed to communicate to the public, or possibly even each other, exactly what rights they intend to take from us — nor what rights will be given in their place.

‘The bottom line is this: when a Government starts to make rights conditional, they cease to become rights and instead become privileges. We must stop the promotion of privilege over the protection of the people.

‘Repealing or scrapping the Human Rights Act would not protect our sovereignty, it would just water down the obligations of the state to treat every one of us with the dignity and respect that we all deserve. Checks and balances are central to ensuring equality and preventing discrimination.’

The plan for the UK’s human rights in the future is ominous. Without cast-iron assurances about the legislation to come, and with the promised separation of our law from the European Court of Human Rights, the people in Britain who are most in need of protection risk being exploited and made vulnerable in order to pander to people with privilege who believe that prisoners having the right to vote or stay in the UK after their sentences is the worst thing in the world.

The rights we are guaranteed under the Human Rights Act are valuable ones that should not be compromised. We would each be less secure, and we would inhabit a less fair country without them, and we should not let them go without a fight.

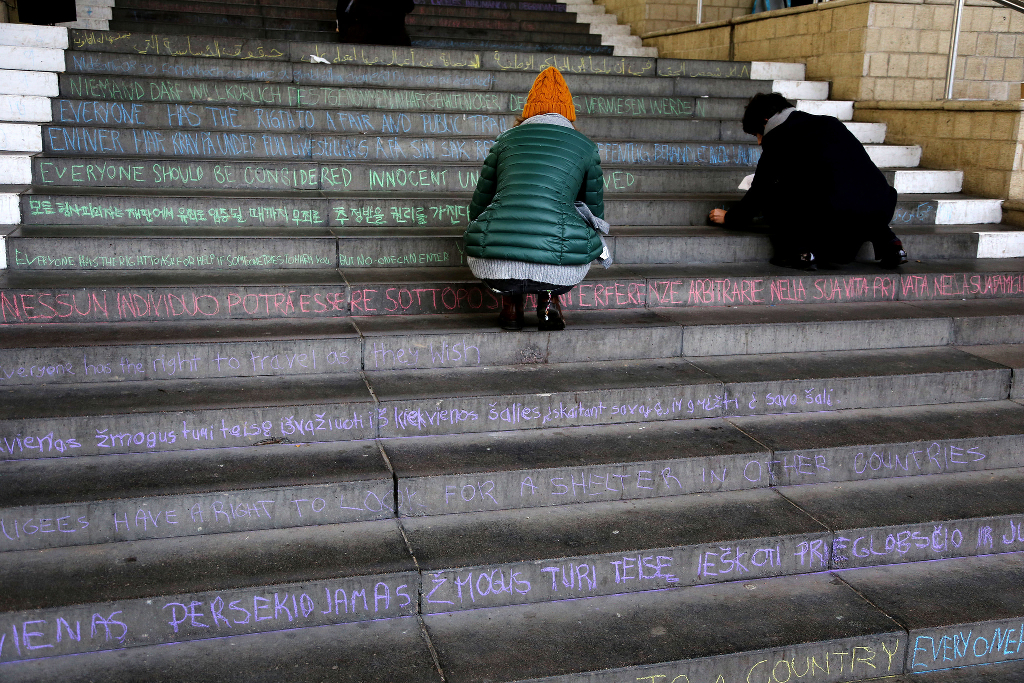

Photo: University of Essex/Creative Commons