Kevin Albertson, Manchester Metropolitan University and Stevienna de Saille, University of Sheffield

Fears over the cost of living have reached new highs in the UK after power regulator Ofgem confirmed that the energy price cap will nearly double from October to cost the average household £3,549 a year. There has been much discussion about what the government needs to do to help people and businesses this winter, but the crisis is still being presented as a short-term problem that will ease in due course.

This is a misdiagnosis. We are actually living through a slow-motion crisis which has been decades in the making and is set to continue. Understanding what is really happening is a vital first step to finding a way out.

We are prone to blame today’s economic mess on short-term factors such as austerity, Brexit, COVID and the war in Ukraine. In fact, global economic headwinds have been gathering strength for years: according to a study reported in the New Scientist a few years ago, 1978 was the best year the world economy ever saw.

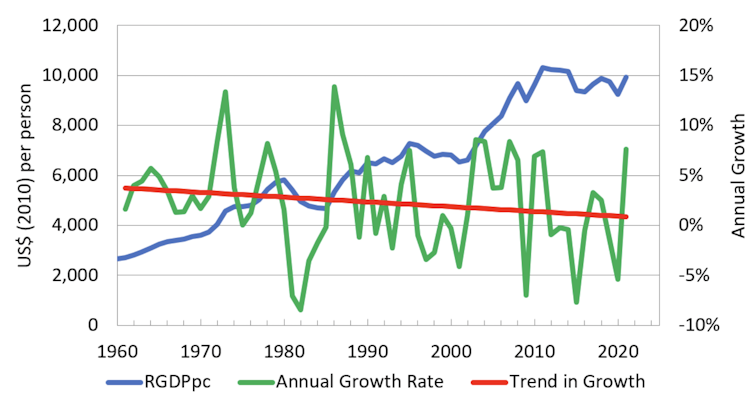

That study argued that growing inequality and environmental degradation have sent progress into reverse, but you can also see decline using traditional economic measures. Global growth in GDP per capita and productivity have been steadily weakening. In the UK, once you take inflation into account, GDP per capita growth has been declining since the 1970s and the average wage is little different than in 2008. In the US, inflation-adjusted median wages peaked in the 1970s.

Real global GDP per capita and growth rate 1960-2021

Author provided

Some argue that the underlying cause of this global problem is a long-term weakness in the US economy. According to influential US think tank the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), much of what has passed for growth has simply been a reallocation of resources from workers to shareholders.

Not only that, it has been achieved by accumulating debt. Financial debt has more than doubled as a percentage of GDP since the early 1970s, while there has also been a build-up of ecological debts by overusing natural resources.

Many leading experts on this so-called “secular stagnation” think it may be here to stay. It is also likely to be more keenly felt in Europe, which has less favourable demographics than the US and fewer natural resources. In 2023, for instance, the OECD is forecasting zero growth in the UK, although a recession (two quarters of negative growth) is probably more likely.

UK not OK

One reason why the UK cost-of-living crisis is so devastating is that many, if not most, people had already seen their standard of living decline before the Ukraine war and COVID. Back in the days of Theresa May (remember the good old days?), there was much talk of “just about managing” households or JAMs, defined as working households with below-average income.

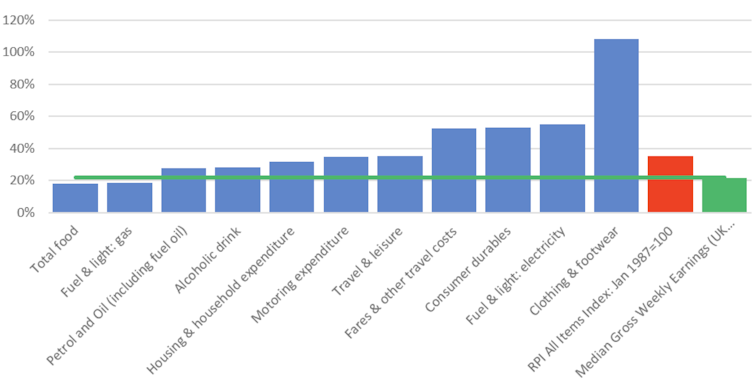

This reflected the fact that well before 2020, many of life’s necessities were increasingly beyond the reach of the average household. Ironically, gas and food were the only necessities whose prices increased by less than median wages from 2009 to 2019. The amount of money that the average household had to spend on discretionary items was falling throughout the decade after adjusting for inflation.

The rising cost of necessities in the 2010s

This slow decline in UK households’ prosperity certainly accelerated sharply because of Ukraine, but ending the war will not end the crisis. For the last few years, energy producers have been investing less in fossil fuel production because they have not been confident about their rate of return in the face of the global push towards net zero carbon emissions.

Since this reduction may be permanent, many experts believe that high oil and gas prices are here to stay. With energy a vital ingredient of economic production, this will further increase the price of almost everything.

Alongside this energy crunch, high debt levels will discourage investment, meaning that the supply of available goods and services will fall. This scarcity is another reason why the upward pressure on prices will continue in the long term. Central banks can do little about it because raising interest rates to tackle inflation only works when an economy is overheating, not when the problem arises from the supply side.

What can be done

Aside from the current panic over the energy price cap, no leading politician is talking seriously about reversing the declining affordability of the essentials of life. Yet, many economists, including ourselves, have been predicting this situation for a long time. As Kevin argued in The Conversation in 2021, the UK government has not done enough to prepare for a “decade of disruption”.

Even if the UK returns to so-called “growth”, it will merely be reverting to the slower, mounting crisis that predated COVID. There is no point in pursuing the globalised free-market policies which failed to prevent secular stagnation in the first place. The crucial first step is rather to get out of our growth-fixated mindset and accurately diagnose the problems we face.

It is clear we must take rapid action to reduce economic precarity, improve social security and incentivise the more efficient use of energy. For example, reducing demand for fossil fuels will be crucial through a major programme of investing in green technologies, as well as interest-free loans for insulating houses and new policies discouraging the wasteful use of resources. In short, there is much to do – and it would take another article really to examine this properly.![]()

Kevin Albertson, Professor of Economics, Manchester Metropolitan University and Stevienna de Saille, Lecturer, Department of Sociological Studies, University of Sheffield

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Matt Collamer